Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble (19 page)

Read Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

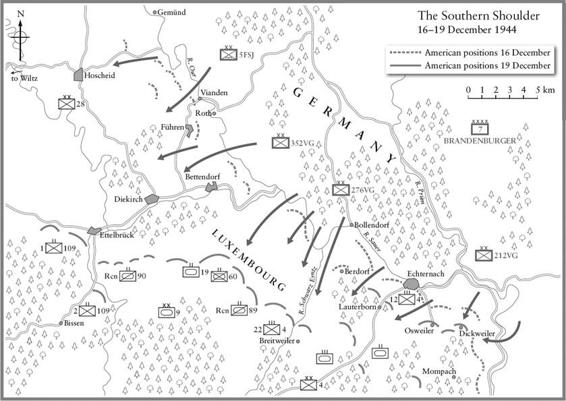

Even though the 26th Volksgrenadiers eventually forced a crossing, repairs to the bridge over the Our near Gemünd were not ready until dusk at 16.00 hours. Traffic jams with the vehicles of both the 26th Volksgrenadier and the Panzer Lehr built up, because the Americans had blocked the road to Hosingen with enormous craters and ‘

abatis

’ barriers of felled trees. German pioneer battalions had to work through the night to make the road passable. The 26th Volksgrenadier lost 230 men and eight officers, including two battalion commanders, on the first day.

On the American 28th Division’s right flank, the German Seventh Army pushed forward the 5th Fallschirmjäger-Division to shield Manteuffel’s flank as his Fifth Panzer Army headed west for the Meuse. But the 5th Fallschirmjäger was a last-minute replacement to the German order of battle and struggled badly. Although 16,000 strong, its officers and soldiers had received little infantry training. One battalion, commanded by the flying instructor Major Frank in the 13th Fallschirmjäger-Regiment, had twelve officers with no field experience. Frank, in a conversation secretly taped after his capture, told another officer that his NCOs were

‘willing but inept’

, while his 700 soldiers were mostly just sixteen or seventeen years old, but ‘the lads were wonderful’.

‘Right on the very first day of the offensive we stormed Führen [held by Company E of the 109th Infantry]. It was a fortified village. We got to within 25 metres of the bunker, were stopped there and my best Kompaniechefs were killed. I stuck fast there for two and a half hours, five of my runners had been killed. One couldn’t direct things from there, the runners who returned were all shot up. Then, for two and a half hours, always on my stomach, I worked my way back by inches. What a show for young boys, making their way over flat ground and without any support from heavy weapons! I decided to wait for a forward observation officer. The Regimental commander said: “Get going. Take that village – there are only a few soldiers holding it.”

‘“That’s madness,” I said to the Regimentskommandeur.

‘“No, no, it’s an order. Get going, we must capture the village before nightfall.”

‘I said: “We will too. The hour we lose waiting for the forward observation officer I will make up two or three times over afterwards … At least give me the assault guns to come in from the north and destroy their bunker.”

‘“No, no, no.”

‘We took the village without any support and scarcely were we in it when our heavy guns began firing into it. I brought out 181 prisoners altogether. I rounded up the last sixty and a salvo of mortar shells fell on them from one of our mortar brigades right into the midst of the prisoners and their guards. Twenty two hours later our own artillery was still firing into the village. Our communications were a complete failure.’

The divisional commander Generalmajor Ludwig Heilmann clearly had no feeling for his troops. Heydte described him as

‘a very ambitious, reckless

soldier with no moral scruples’, and said that he should not be commanding a division. His soldiers called him

‘der Schlächter von Cassino’

, the butcher of Cassino, because of the terrible losses suffered by his men during that battle. And on the first day of the

Ardennes offensive, his units were battered

by American mortar fire as they floundered across the River Our, which was fast flowing and had a muddy bottom.

Just to the south the American 9th Armored Division held a narrow three-kilometre sector, but was pushed back by the 212th Volksgrenadier-Division. To its right, outposts of the 4th Infantry Division west and south of Echternach failed to see German troops crossing the Sauer before dawn. Their outposts on bluffs or ridges high above the river valley may have had a fine view in clear weather, but at night and on misty days they were blind. As a result most of the men in these forward positions were surrounded and captured very rapidly because German advance patrols had slipped through behind them. A company commander, while finally reporting details of the attack by field telephone to his battalion commander, was startled to hear another person on the line. A voice with a heavy German accent announced:

‘We are here!’

One squad in Lauterborn was caught entirely by surprise and taken prisoner. But the over-confident Germans marched them down the road past a mill, which happened to be occupied by Americans from another company who opened fire. The prisoners threw themselves in the ditch where they hid for several hours, and then rejoined their unit later.

Once again, field telephone lines back from observation posts were cut by shellfire and radios often failed to work due to the hilly terrain and damp atmospheric conditions. Signals traffic was in any case chaotic, with careless or panic-stricken operators jamming everyone else. Major General Raymond O. Barton, the commander of the 4th Infantry Division, only heard at 11.00 hours that his 12th Infantry Regiment either side of Echternach was under strong attack. Barton wasted no time in committing his reserve battalion and sending in a company from the 70th Tank Battalion. As darkness fell later that afternoon, the 12th Infantry still held five key towns and villages along the ridge route of ‘Skyline Drive’. These were the all-important crossroads which blocked the German advance.

‘It was the towns and road

junctions that proved decisive in the battle,’ concluded one analysis.

The 4th Infantry had also dropped tall pines across the roads to make abatis barriers, which were mined and booby-trapped. The division’s achievement was all the more remarkable when considering its shortages in manpower and weaponry after its recent battles in the Hürtgen Forest. Ever since the fighting in Normandy, the 4th Infantry Division had seized as many Panzerfausts as it could to use them back against the Germans. Although their effective range was only about forty metres, the infantrymen found them much more powerful in penetrating the Panther tank than their own bazooka. Forty-three of their fifty-four tanks were still undergoing repair in workshops to the rear. This did not prove as disastrous as it might have done. Manteuffel had wanted to provide Brandenberger’s Seventh Army with a panzer division to break open the southern shoulder, but none could be spared.

General Bradley’s journey that day on the icy roads from Luxembourg to Versailles took longer than expected. Eisenhower was in an expansive mood when he arrived, for he had just heard that he was to receive his fifth star. Bradley congratulated him. ‘God,’ Eisenhower answered,

‘I just want to see the first time I sign

my name as General of the Army.’

Major Hansen, who had accompanied Bradley, returned to the Ritz where Hemingway was drinking with a large number of visitors.

‘The room, with two brass beds,’

wrote Hansen, ‘was littered in books which overflowed to the floor, liquor bottles and the walls were fairly covered with prints of Paris stuck up carelessly with nails and thumbtacks.’ After talking with them for a time, Hansen ‘ducked out and walked wearily to the Lido where we saw bare breasted girls do the hootchy kootchie until it was late’.

At the end of the afternoon, while Eisenhower and Bradley were discussing the problem of replacements with other senior officers from SHAEF, they were interrupted by a staff officer. He handed a message to Major General Strong who, on reading it, called for a map of the VIII Corps sector. The Germans had broken through at five points, of which the most threatening was the penetration via the Losheim Gap. Although details were sparse, Eisenhower immediately sensed that this was serious, even though there were no obvious objectives in the Ardennes. Bradley, on the other hand, believed that this was simply the spoiling attack he had half expected to disrupt Patton’s offensive in Lorraine. Eisenhower wasted no time after consulting the operations map. He gave orders that the Ninth Army should send the 7th Armored Division to help Troy Middleton in the Ardennes, and that Patton should transfer his 10th Armored Division. Bradley remarked that Patton would not be happy giving it up with his offensive about to start in three days.

‘Tell him’, Eisenhower snarled, ‘that

Ike is running this war.’

Bradley had to ring Patton straight away. As he had predicted, Patton complained bitterly, and said that the German attack was just an attempt to disrupt his own operation. With Eisenhower’s eyes upon him, Bradley had to give him a direct order. The men of the 10th Armored Division were horrified to hear that they were to be transferred from Patton’s Third Army to First Army reserve.

‘That broke our hearts

because, you know, First Army – hell we were in Third Army.’ Patton, however, had an instinct just after the telephone call that it

‘looks like the real thing’

.

‘It reminds me very much

of March 25, 1918 [Ludendorff’s offensive]’, he wrote to a friend, ‘and I think will have the same results.’

Bradley then rang his headquarters in Luxembourg and told them to contact Ninth Army. He did not expect any trouble there. Lieutenant General William H. Simpson was a tall but quietly spoken Texan known as ‘the doughboy general’, whom everybody liked. He had an engaging long face on a bald head with prominent ears and a square chin. Simpson was examining the air-support plan for crossing the Roer when at 16.20 hours, according to his headquarters diary, he received a call from Major General Allen, the chief of staff at 12th Army Group.

‘Hodges [is] having a bit of trouble on his south flank,’

Allen said. ‘There is a little flare-up south of you.’ Simpson immediately agreed to release the 7th Armored Division to First Army. Exactly two hours later, Simpson rang to check that the advance party of the 7th Armored Division was on its way.

Eisenhower and Bradley, having despatched the two divisions, drank a bottle of champagne to celebrate the fifth star. The Supreme Commander had just received a supply of oysters which he loved, but Bradley was allergic to them and ate scrambled eggs instead. Afterwards they played five rubbers of bridge, since Bradley was not returning to Luxembourg until the following morning.

While the two American generals were in Versailles, Oberstleutnant von der Heydte in Paderborn was woken from a deep sleep by a telephone call. He was exhausted because everything had gone wrong the night before and he had not been to bed. His Kampfgruppe had been due to take off in the early hours of that morning, but most of the trucks to bring his men to the airfield had not received fuel in time, so

the operation had been postponed; then it looked as if it would be cancelled. General Peltz, the Luftwaffe general on the telephone, now told him that the jump was back on because the initial attack had not progressed as rapidly as hoped.

When Heydte reached the airfield, he heard that the meteorological report from Luftflotte West estimated a wind speed of twenty kilometres per hour over the drop zone. This was the highest speed permissible for a night drop on a wooded area, and Heydte was being deliberately misinformed so that he would not cancel the operation. Just after all the paratroopers had climbed aboard the elderly Junkers 52 transport planes, a

‘very conscientious meteorologist’

rushed up to Heydte’s plane as it was about to taxi, and said: ‘I feel I must do my duty; the reports from our sources are that the wind is 58 kph.’

The whole operation turned into a fiasco. Because most of the pilots were

‘new and nervous’

and unused to navigating at night, some 200 of Heydte’s men were dropped around Bonn. Few of the jumpmasters had ever performed their task before, and only ten aircraft managed to drop their sticks of paratroopers on the drop zone south of Eupen, which had been marked by two magnesium flares. The wind was so strong that some paratroopers were blown on to the propellers of the following aircraft. Survivors of the landing joined up in the dark by whistling to each other. By dawn Heydte knew that his mission was

‘an utter failure’

. He had assembled only 150 men, a

‘pitifully small muster’

, he called it, and very few weapon containers were found. Only eight Panzerfausts out of 500 were recovered and just one 81mm mortar.

‘German People, be confident!’

stated Adolf Hitler’s message to the nation. ‘Whatever may face us, we will overcome it. There is victory at the end of the road. Under any situation, in battle where the fanaticism of a nation is a factor, there can only be victory!’ Generalfeldmarschall Model declared in an order of the day to the troops of Army Group B:

‘We will win, because we believe in Adolf Hitler and the Greater German Reich!’

But that night some 4,000 German civilians died in an Allied bombing raid on Magdeburg, which had been planned before the offensive.

Belgian civilians at least had the choice of fleeing the onslaught, but

some stayed with their farms and animals, resigned to another German occupation. They did not know, however, that the SS Sicherheitsdienst security service was following hard on the heels of Waffen-SS formations. As far as these SD units were concerned, the inhabitants of the eastern cantons were German citizens and they wanted to know who had disobeyed the orders in September to move east of the Siegfried Line with their families and livestock. Locals avoiding service in the Wehrmacht and those who had collaborated with the Americans during the autumn were liable to arrest, and even execution in a few cases. But their main targets were those young Belgians in Resistance groups which had harried the retreating German forces in September.