Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble (4 page)

Read Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

With Red Army forces now on the East Prussian border, Hitler was afraid of a Soviet parachute operation to capture him. The Wolfsschanze had been turned into a fortress.

‘By now a huge

apparatus had been constructed,’ wrote his secretary Traudl Junge. ‘There were barriers and new guard posts everywhere, mines, tangles of barbed wire, watchtowers.’

Hitler wanted an officer whom he could trust to command the troops defending him. Oberst Otto Remer had brought the

Grossdeutschland

guard battalion in Berlin to defeat the plotters on 20 July, so on hearing of Remer’s request to be posted back to a field command, Hitler summoned him to form a brigade to guard the Wolfsschanze. Initially based on the Berlin battalion and the

Hermann Göring

Flak-Regiment with eight batteries, Remer’s brigade grew and grew. The

Führer Begleit

, or Führer Escort, Brigade was formed in September ready to defend the Wolfsschanze against

‘an air landing

of two to three airborne divisions’. What Remer himself called this

‘unusual array’

of combined arms was given absolute priority in weapons, equipment and ‘experienced front-line soldiers’ mostly from the

Grossdeutschland

Division.

The atmosphere in the Wolfsschanze was profoundly depressed. For some days Hitler retired to his bed and lay there listlessly while his secretaries were

‘typing out whole reams

of reports of losses’ from both eastern and western fronts. Göring meanwhile was sulking on the Hohenzollern hunting estate of Rominten which he had appropriated in East Prussia. After the failure of his Luftwaffe in Normandy, he knew that he had been outmanoeuvred by his rivals at the Führer’s court, especially the manipulative Martin Bormann who was eventually to prove his nemesis. His other opponent, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, had been given command of the Ersatzheer – the Replacement Army – in whose headquarters the bomb plot had been hatched. And Goebbels appeared to have complete command of the home front, having been appointed Reich Plenipotentiary for the Total War Effort. But Bormann and the Gauleiters could still thwart almost any attempt to exert control over their fiefdoms.

Although most Germans had been shocked by the attempt on Hitler’s life, a steep decline in morale soon followed as Soviet forces advanced to the borders of East Prussia. Women above all wanted the war to end and, as the security service of the SS reported, many had lost faith in the Führer. The more perceptive sensed that the war could not end while he remained alive.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the successes of that summer, rivalries were stirring in the highest echelons of the Allied command. Eisenhower,

‘a military statesman

rather than a warlord’ as one observer put it, sought consensus, but to the resentment of Omar Bradley and the angry contempt of George Patton, he seemed bent on appeasing Montgomery and the British. The debate, which was to inflame relations throughout the rest of 1944 and into the new year, had begun on 19 August.

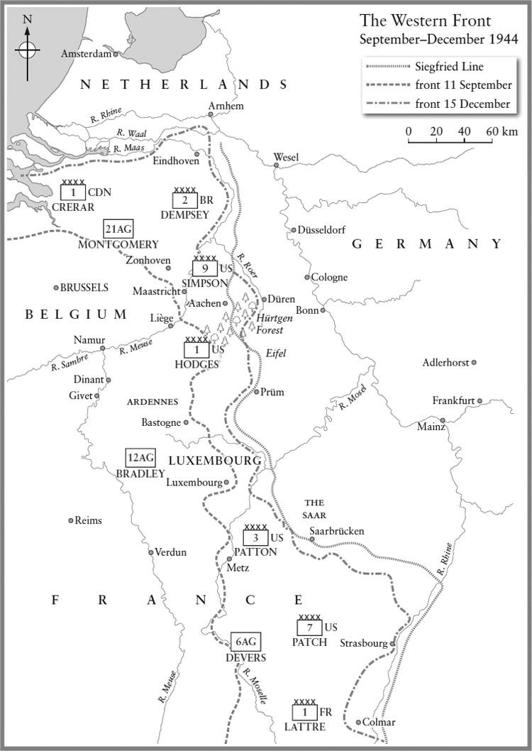

Montgomery had demanded that almost all Allied forces should advance under his command through Belgium and Holland into the industrial region of the Ruhr. After this proposal had been rejected, he wanted his own 21st Army Group, supported by General Courtney Hodges’s First Army, to take this route. This would enable the Allies to capture the V-weapon launch sites bombarding London and take the deep-water port of Antwerp, which was vital to supply any further advances. Bradley and his two army commanders, Patton and Hodges, agreed that Antwerp must be secured, but they wanted to go east to the Saar, the shortest route into Germany. The American generals felt that

their achievements in Operation Cobra, and the breakout all the way to the Seine led by Patton’s Third Army, should give them the priority. Eisenhower, however, knew well that a single thrust, whether by the British in the north or by the Americans in the middle of the front, ran grave political dangers, even more than military ones. He would have the press and the politicians in either the United States or Great Britain exploding with outrage if their own army was halted because of supply problems while the other pushed on.

On 1 September, the announcement of the long-standing plan for Bradley, who had technically been Montgomery’s subordinate, to assume command of the American 12th Army Group prompted the British press to feel aggrieved once again. Fleet Street saw the reorganization as a demotion for Montgomery because, with Eisenhower now based in France, he was no longer ground forces commander. This problem had been foreseen in London, so to calm things down Montgomery was promoted to field marshal (which in theory made him outrank Eisenhower, who had only four stars). Listening to the radio that morning, Patton was sickened when

‘Ike said that Monty

was the greatest living soldier and is now a Field Marshal.’ No mention was made of what others had achieved. And after a meeting at Bradley’s headquarters next day, Patton, who had led the charge across France, noted:

‘Ike did not thank

or congratulate any of us for what we have done.’ Two days later his Third Army reached the River Meuse.

In any event, the headlong advance by the US First Army and the British Second Army to Belgium proved to be one of the most rapid in the whole war. It might have been even faster if they had not been delayed in every Belgian village and town by the local population greeting them with rapture. Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, the commander of XXX Corps, remarked that

‘what with champagne

, flowers, crowds, and girls perched on the top of wireless trucks, it was difficult to get on with the war’. The Americans also found that their welcome in Belgium was far warmer and more enthusiastic than it had been in France. On 3 September, the Guards Armoured Division entered Brussels to the wildest scenes of jubilation ever.

The very next day, in a remarkable

coup de main

, Major General ‘Pip’ Roberts’s 11th Armoured Division entered Antwerp. With the assistance of the Belgian Resistance, they seized the port before the Germans could

destroy its installations. The 159th Infantry Brigade attacked the German headquarters in the park, and by 20.00 hours the commander of the German garrison had surrendered. His 6,000 men were marched off to be held in empty cages in the zoo, the animals having been eaten by a hungry population.

‘The captives sat on the straw

,’ Martha Gellhorn observed, ‘staring through the bars.’ The fall of Antwerp shocked Führer headquarters.

‘You had barely crossed

the Somme,’ General der Artillerie Walter Warlimont acknowledged to his Allied interrogators the following year, ‘and suddenly one or two of your armoured divisions were at the gates of Antwerp. We had not expected any breakthrough so quickly and nothing was ready. When the news came it was a bitter surprise.’

The American First Army also moved fast to catch the retreating Germans. The reconnaissance battalion of the 2nd Armored Division, advancing well ahead of other troops, identified the enemy’s route of withdrawal, then took up ambush positions with light tanks in a village or town just after dark.

‘We would let

a convoy get within [the] most effective range of our weapons before we opened fire. One light tank was used to tow knocked out vehicles into hiding among buildings in the town to prevent discovery by succeeding elements. This was kept up throughout the night.’ One American tank commander calculated that from 18 August to 5 September his tank had done 563 miles

‘with practically no maintenance’

.

On the Franco-Belgian border, Bradley’s forces had an even greater success than the British with a pincer movement meeting near Mons. Motorized units from three panzer divisions managed to break out just before the US 1st Infantry Division sealed the ring. The paratroopers of the 3rd and 6th Fallschirmjäger-Divisions were bitter that once again the Waffen-SS had saved themselves, leaving everybody else behind. The Americans had trapped the remnants of six divisions from Normandy, altogether more than 25,000 men. Until they surrendered they were sitting ducks. The 9th Infantry Division artillery reported:

‘We employed

our 155mm guns in a direct fire role against enemy troop columns, inflicting heavy casualties and contributing to the taking of 6,100 prisoners including three generals.’

Attacks by the Belgian Resistance in the Mons Pocket triggered the first of many reprisals, with sixty civilians killed and many houses set on fire. Groups of the Armée Secrète from the Mouvement National Belge,

the Front de l’Indépendance and the Armée Blanche worked closely with the Americans in the mopping-up stage.

*

The German military command became angry and fearful of a mass rising as their forces retreated through Belgium to the safety of the

Westwall

, or Siegfried Line as the Allies called it. Young Belgians flocked to join in the attacks, with terrible consequences both at the time and later in December when the Ardennes offensive brought back German forces, longing for revenge.

On 1 September, in Jemelle, near Rochefort in the northern Ardennes, Maurice Delvenne watched the German withdrawal from Belgium with pleasure.

‘The pace of the retreat

by German armies accelerates and seems increasingly disorganized,’ he wrote in his diary. ‘Engineers, infantry, navy, Luftwaffe and artillery are all in the same truck. All of these men have obviously just been in the combat zone. They are dirty and haggard. Their greatest concern is to know how many kilometres still separate them from their homeland, and naturally we take a spiteful pleasure in exaggerating the distance.’

Two days later SS troops, some with bandaged heads, passed by Jemelle.

‘Their looks are hard

and they stare at people with hatred.’ They were leaving a trail of destruction in their wake, by burning buildings, tearing down telegraph lines and driving stolen sheep and cattle before them. Farmers in the German-speaking eastern cantons of the Ardennes were ordered to move with their families and livestock back behind the Siegfried Line and into the Reich. News of the Allied bombing was enough to discourage them, but most simply did not want to leave their farms, so they hid with their livestock in the woods until the Germans had gone.

On 5 September, the exploits of young

résistants

provoked the retreating Germans into burning thirty-five houses beside the N4 highway from Marche-en-Famenne towards Bastogne, near the village of Bande. Far worse was to follow on Christmas Eve when the Germans returned in the Ardennes offensive. Ordinary people were terrified by the reprisals that followed Resistance attacks. At Buissonville on 6 September the

Germans took revenge for an attack two days before. They set fire to twenty-two houses there and in the next-door village.

Further along the line of retreat, villagers and townsfolk turned out with Belgian, British and American flags to welcome their liberators. Sometimes they had to hide them quickly when yet another fleeing German detachment appeared in their main street. Back in Holland at Utrecht, Oberstleutnant Fritz Fullriede described

‘a sad platoon of Dutch

National Socialists being evacuated to Germany, to flee the wrath of the native Dutch. Lots of women and children.’ These Dutch SS had been fighting at Hechtel over the Belgian border. They had escaped the encirclement by swimming a canal, but ‘the wounded officers and men who wanted to give themselves up were for the most part – to the discredit of the British [who apparently stood by] – shot by the Belgians’. Both Dutch and Belgians had much to avenge after four years of occupation.

The German front in Belgium and Holland appeared completely broken. There was panic in the rear with chaotic scenes which prompted the LXXXIX Army Corps to speak in its war diary of

‘a picture that is unworthy

and disgraceful for the German army’. Feldjäger Streifengruppen, literally punishment groups, seized genuine stragglers and escorted them to a collection centre, or

Sammellager

. They were then sent back into the line under an officer, usually in batches of sixty. Near Liège, around a thousand men were marched to the front by officers with drawn pistols. Those suspected of desertion were court-martialled. If found guilty, they were sentenced either to death or to a Bewährungsbataillon (a so-called probation battalion, but in fact more of a punishment or Strafbataillon). Deserters who confessed, or who had put on civilian clothes, were executed on the spot.

Each Feldjäger wore a red armband with

‘OKW Feldjäger’

on it and possessed a special identity card with a green diagonal stripe which stated: ‘He is entitled to make use of his weapon if disobeyed.’ The Feldjäger were heavily indoctrinated. Once a week an officer lectured them on

‘the world situation

, the impossibility of destroying Germany, on the infallibility of the Führer and on underground factories which should help outwit the enemy’.

Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model’s ‘Appeal to the Soldiers of the

Army of the West’ went unheeded when he called on them to hold on, to gain time for the Führer. The most ruthless measures were taken. Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel ordered on 2 September that

‘malingerers and cowardly shirkers

, including officers’ should be executed immediately. Model warned that he needed a minimum of ten infantry divisions and five panzer divisions if he were to prevent a breakthrough into northern Germany. No force of that magnitude was available.