Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble (9 page)

Read Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Men often arrived with none of the training qualifications which their forms stated. Many could not swim. After losing a large number of men crossing the Moselle, a company commander in Patton’s Third Army described the attack on Fort Driant with replacements for his casualties.

‘We couldn’t get the new untrained and inexperienced

troops to move. We had to drag them up to the fort. The old men were tired and the new afraid and as green as grass. The three days we spent in the breach of the fort consisted in keeping the men in the lines. All the leaders were lost exposing themselves at the wrong time in order to get this accomplished. The new men seemed to lose all sense of reasoning. They left their rifles, flamethrowers, satchel charges and what not laying right where it was. I was disgusted and so damned mad I couldn’t see straight. If it had not been for pre-planned defensive artillery fire [the Germans] would have shoved us clean out of the fort with the caliber of troops we had. Why? – The men wouldn’t fight. Why wouldn’t they fight? – They had not been trained nor disciplined to war.’

In all too many cases, replacements joined their platoon at night, not knowing where they were or even which unit they were with. They were

often shunned by the survivors of the platoon they were joining who had lost close buddies. And because replacements were seen as clumsy and doomed, the veterans kept their distance. This became almost a self-fulfilling prophecy as badly led platoons would use the new arrivals for the most dangerous tasks rather than risk an experienced soldier. Many never survived the first forty-eight hours.

Replacements were sometimes treated little better than expendable slaves, and the whole system bred a cynicism which was deeply troubling. Martha Gellhorn, in her novel

Point of No Return

, repeats a clearly common piece of black humour:

‘Sergeant Postalozzi

says they ought to shoot the replacements at the repple depple and save trouble. He says it just wastes time carrying all them bodies back.’

*

Only if a replacement was still alive after forty-eight hours at the front, did he stand a hope of surviving a little longer. One of Bradley’s staff officers mused on the fate of a newly arrived ‘

doughboy

’.

‘His chances seem at their

highest after he has been in the line – oh, perhaps a week. Then you know, sitting in a high headquarters, like an actuary behind an insurance desk, that the odds on his survival drop slowly but steadily and with mathematical certainty always down, down, down. The odds drop for every day he remains under fire until, if he’s there long enough, he is the lone number on a roulette wheel which hasn’t come up in a whole evening of play. And he knows it too.’

‘I was lucky

to be with old soldiers who wanted to help a new replacement to survive,’ Arthur Couch wrote of his good fortune to be sent to the 1st Infantry Division. He was taught to fire a burst with the Browning Automatic Rifle, then immediately roll sideways to a new position because the Germans would direct all their fire back at any automatic weapon. Couch learned quickly, but he must have been in a minority.

‘The quality of replacements

has declined appreciably in recent weeks,’ his division reported on 26 October. ‘We receive too many men not physically fit for infantry combat. We have received some men forty-years-old who cannot take exposure to cold, mud, rain etc. Replacements are not sufficiently prepared mentally for combat. They have not been

impressed with the realities of war – as evidenced by one replacement inquiring if they were using live ammunition on the front.’

Front-line divisions were furious with the lack of training before their arrival.

‘Replacements have 13 weeks basic training,’

a sergeant in III Corps commented. ‘They don’t know [the] first thing about a machinegun, don’t know how to reduce stoppage or get the gun in action quickly. They are good men but have not been trained. Up in the fight is no place to train them.’ Another sergeant said that, in training back in the States, the raw recruits had been told that

‘enemy weapons could be silenced

and overcome by our weapons’. They arrived thinking the only danger was from small-arms fire. They had not imagined mines, mortars, artillery and tanks. In an attack, they bunched together, offering an easy target. When a rifle fired or a machine gun opened up, they would throw themselves flat on the ground, exposing themselves to mortar bursts, when the safest course was to rush forward.

The principle of ‘marching fire’, keeping up a steady volume at likely targets as they advanced, was something that few replacements seemed able to comprehend.

‘The worst fault I have found’

, reported a company commander, ‘has been the failure of men to fire weapons. I have seen them fired on and not fire back. They just took cover. When questioned, they said to fire would draw fire on themselves.’ Paradoxically, when German soldiers tried to surrender, replacements were nearly always the first to try to shoot them down, which made them go to ground and fight on. Newcomers also needed to learn about German tricks which might throw them.

‘Jerry puts mortar fire

just behind our own artillery fire to make our troops believe that their own fire is falling short.’ Experienced troops were well used to this, but replacements often panicked.

Divisions also despaired at the lack of preparation for officer and NCO replacements. They argued that officers needed to serve at the front before being given responsibility for men’s lives. NCOs who arrived without any combat experience should be reduced in rank automatically before they arrive, and then be promoted again once they had proved they could do the job.

‘We actually had a master sergeant sent to us,’

one division reported. ‘All he had done since being in the Army was paint a mural in the Pentagon. He is a good man but we have no job for him in grade.’

‘My first contact

with the enemy found me rather in a dazed frame of mind,’ a young officer replacement admitted. ‘I could not quite grasp the significance of what it was all about … It took me about four days to get where I did not think every shell that came over was for me.’ He doubtless turned out to be a good platoon leader. But many, through no fault of their own, were utterly unsuited to the task. Some lieutenants were sent to tank battalions having never seen the inside of a tank. An infantry division was horrified to receive

‘one group of officer

replacements [who] had no experience as platoon leaders. They had been assistant special service officers, mess officers, etc.’

Commanders, in an attempt to galvanize their replacements, tried to stir up a hatred of the enemy.

‘Before entering combat

I have my leaders talk up German inhumanities,’ stated a battalion commander with the 95th Division involved in the reduction of fortresses at Metz. ‘Now that we have been in combat, we have lots of practical experience to draw on in this regard and it takes little urging to get the men ready to tear the Boche limb from limb. We avoid putting it on thick but merely try to point out that the German is a breed of vicious animal which will give us no quarter and must be exterminated.’

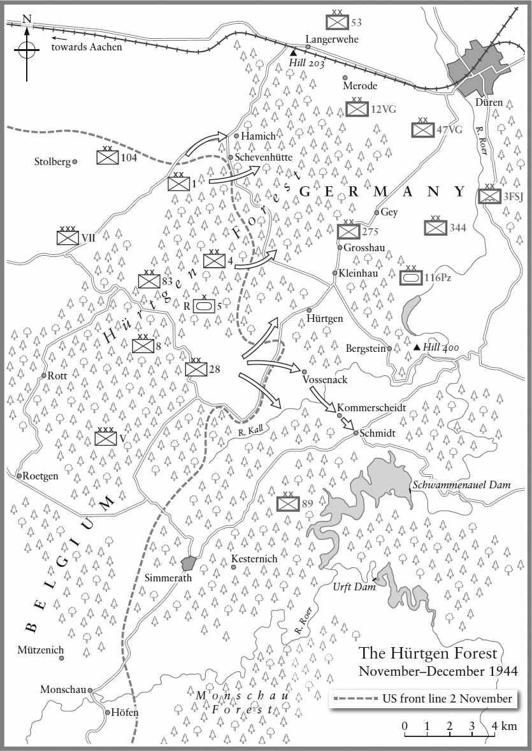

The Hürtgen Forest

Hemingway’s friend and hero Colonel Buck Lanham of the 4th Division had soon found himself back in a world far removed from the comforts of the Ritz. At the end of October, General Eisenhower issued his orders for the autumn campaign. While the Canadian First Army finished securing the Scheldt estuary to open the port of Antwerp, the other six Allied armies under his command would advance to the Rhine with the industrial regions of the Ruhr and the Saar as their next objectives.

First Army’s breaching of the Siegfried Line round Aachen put it no more than thirty kilometres from the Rhine, a tantalizingly small distance on the map. Some fifteen kilometres to the east lay the

Roer river

, which would have to be crossed first. The left wing of First Army, supported by the Ninth Army just to its north, would prepare to cross as soon as Collins’s VII Corps and Gerow’s V Corps secured the Hürtgen Forest and adjoining sectors.

Lieutenant General Courtney H. Hodges chose the old health resort of Spa for his headquarters. At the end of the First World War, Spa had been the base for Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg and Kaiser Wilhelm II. There, in November 1918, the leadership of the Second Reich faced the sudden disintegration of their power as mutinies broke out back in Germany: the ‘stab in the back’ which Hitler was now obsessed with preventing twenty-six years later. Hodges took over the Grand Hôtel Britannique, while his operations staff set up their collapsible tables and situation maps under the chandeliers in the casino. The town’s parks were packed with Jeeps and other military vehicles which

had churned the grass into a mass of mud. The combat historian Forrest Pogue noted that, although less than thirty kilometres from the front line, nobody bothered to carry a weapon or wear field uniform.

First Army headquarters was not a happy place. It reeked of resentment and frustration at the slow progress during that stalemated autumn. Hodges, a strictly formal, colourless man with a clipped moustache, always held himself erect and seldom smiled. He had a southern drawl, was reluctant to take quick decisions and showed a lack of imagination for manoeuvre: he believed in simply going head-on at the enemy. More like a businessman in head office than a soldier, he hardly ever visited the front forward of a divisional command post. His decision to attack straight through the Hürtgen Forest as part of the plan to close with the Rhine led to the most gruesome part of the whole north-west Europe campaign.

South-east of Aachen, the Hürtgen Forest was a semi-mountainous expanse of deep pinewoods, with a few patches of oak and beech and some pasture on the ridges. Before the noise of war dominated its eerie peace, the only sounds were those of the wind in the trees and the mew of buzzards circling above. The forest, riven diagonally by ravines, had all too many vertiginous slopes. They were too steep for tanks and exhausting for heavily laden infantry, slipping and sliding amid the mud, rock and roots. The pine forest was so dense and so dark that it soon seemed cursed, as if in a sinister fairy-tale of witches and ogres. Men felt that they were intruders, and conversed in whispers as if the forest might be listening.

Tracks and firebreaks gave little sense of direction in this area of just under 150 square kilometres. There was little sign of human habitation except for a handful of villages, with woodcutters’ houses and farms built in the local grey-brown stone at ground level, and timber-framed above. Piles of firewood were neatly stacked under shelters outside each dwelling.

After the initial forays into the edge of the forest by the 3rd Armored and the 1st Infantry Divisions in the second week of September, Hodges and his staff should have realized what they were asking their troops to take on. The subsequent experience of the 9th Infantry Division during the second half of September and October should have been a further warning. Progress had been good at first, advancing south-east towards

the key town of Schmidt. Surprise was achieved because, in the words of the German divisional commander facing them,

‘In general it was believed

to be out of the question that in this extensive wooded area which was difficult to survey and had only a few roads, the Americans would try to fight their way to the Roer.’ Once the German infantry were supported by their corps artillery, the forest fighting turned into a terrible battle of attrition.

The Germans brought in snipers to work from hides fixed high in the trees (closer to the ground there was little field of vision). They had been trained at Munsterlager in a

Scharfschutzen-Ausbildungskompanie

, or sniper-training company, where every day they had been subjected to half an hour of hate propaganda.

‘This consisted

of a kind of frenzied oration of the NCO instructors and usually took the following form:

‘NCO: “Every shot must kill a Jewish Bolshevik.”

‘Chorus: “Every shot.”

‘NCO: “Kill the British Swine.”

‘Chorus: “Every shot must kill.”’

The American 9th Infantry Division was attacking the sector held by the 275th Infanterie-Division led by Generalleutnant Hans Schmidt. Schmidt’s regiments’ command posts were log-huts in the forest. The division was only 6,500 strong with just six self-propelled assault guns. It had some soldiers with an idea of forest fighting, but others, such as the 20th Luftwaffe Festbataillon, had no infantry experience. One of its companies consisted of the Luftwaffe Interpreter School, which in Schmidt’s view was

‘absolutely unfit for employment at the front’

. The following month

‘almost the entire company went over to the enemy’

. His troops were armed with a mixture of rifles, taken from foreign countries occupied earlier in the war.

Fighting in the Hürtgen Forest, Schmidt acknowledged, made

‘the greatest demands on [the soldiers’

] physical and psychological endurance’. They survived only because the Americans could not profit from their overwhelming superiority in tanks and airpower, and artillery observation was very difficult. But German supplies and rear-echelon personnel suffered badly from fighter-bomber attacks. The difficulties of bringing hot food forward meant that German troops received nothing but

‘cold rations at irregular intervals.’

Men in soaking uniforms had to remain in their foxholes for days in temperatures close to freezing.

On 8 October, the division was joined by Arbeitsbataillon 1412, consisting of old men.

‘It was like a drop of water on a hot stove,’

Schmidt commented. Virtually the whole battalion was annihilated in the course of a single day. An officer cadet battalion from the Luftwaffe was also torn to pieces. And on 9 October, when the division had already suffered 550 casualties

‘without counting the great number of sick’

, a police battalion from Düren was thrown into the battle east of Wittscheide. The men, aged between forty-five and sixty, were still in their green police uniforms and had received no training since the First World War.

‘The commitment of the old paterfamilias was painful,’

Schmidt admitted. Casualties were so heavy that staff officers and training NCOs from the Feldersatzbataillon, their reserve and replacement unit, had to be sent forward to take command. Even badly needed signallers were sent in as infantrymen.

Only the very heavy rain on 10 October gave the 275th Division the chance to re-establish its line. Schmidt was impressed by the American 9th Infantry Division and even wondered whether it had received special training in forest warfare. That afternoon when his corps and army commanders paid a visit, they were so shaken by the condition of the division that they promised reinforcements.

Reinforcements did arrive, but to launch a counter-attack rather than strengthen the line. They consisted of a well-armed training regiment 2,000 strong, half of whom were officer candidates, commanded by Oberst Helmuth Wegelein. Hopes were high. The attack was launched at 07.00 hours on 12 October with heavy artillery support. But, to the despair of German officers, the advance became bogged down under very effective American fire. It appears that the battalion commanders of this elite training regiment became confused and the whole attack collapsed in chaos. A second attempt in the afternoon also failed. Training Regiment Wegelein lost 500 men in twelve hours, and Wegelein himself was killed the next day. On 14 October, the Germans were forced to pull back to reorganize, but as General Schmidt guessed with relief, the American 9th Division was also totally exhausted.

The 9th Division’s painful and costly advance came to a halt on 16 October after it had suffered some 4,500 battle and non-battle casualties: one for every yard it had advanced. American army doctors, operating on both badly wounded GIs and German soldiers, had begun to notice a striking contrast. Surgeons observed that

‘the German soldier shows

an aptitude for recovery from the most drastic wounds far above that of the American soldier’. This difference was apparently due to ‘the simple surgical fact that American soldiers, being so much better fed than the Germans, generally have a thick layer of fat on them which makes surgery not only more difficult and extensive, but also delays healing. The German soldier on the other hand, being sparsely fed and leaner, is therefore more operable.’

To the dismay of divisional commanders, First Army headquarters was unmoved by the casualties of the 9th Division’s offensive and still took no account of the terrain. Once again Hodges insisted on attacking through the most difficult parts and the thickest forest, where American advantages in tank, air and artillery support could never play a part. He never considered advancing on the key town of Schmidt from the Monschau corridor to the south, a shorter and generally easier approach. The trouble was that neither his corps commanders nor his headquarters staff dared to argue with him. Hodges had a reputation for sacking senior officers.

The First Army plan for the Hürtgen Forest had never mentioned the Schwammenauel and Urft dams south of Schmidt. The idea had simply been to secure the right flank and advance to the Rhine. Hodges did not listen to any explanation of the problems the troops faced. In his view, such accounts were simply excuses for a lack of guts. Radios worked badly in the deep valleys, heavy moisture and dense pinewoods. A back-up signaller was always needed since the Germans targeted anyone with a radio pack on his back. The Germans were also swift to punish any lapses in wireless security. The slip of a battalion commander who said in clear over the radio

‘I am returning in half an hour’

led to two of his party being killed in a sudden mortar bombardment on their customary route back to the regimental command post.

The trails and firebreaks in the forest were misleading and did not correspond to the maps, which inexperienced officers found hard to read anyway.

‘In dense woods,’

a report observed, ‘it is not too infrequent for a group to be completely lost as to directions and front line.’ They needed the sound of their own artillery to find their way back. Sometimes they had to radio the artillery to fire a single shell on a

particular point to reorientate themselves. And at night men leaving their foxhole could get completely lost just a hundred metres from their position, and would have to wait until dawn to discover where they were.

Most unnerving of all were the screams of those who had stepped on an anti-personnel mine and lost a foot.

‘One man kicked a bloody shoe from his path,’

a company commander later wrote, ‘then shuddered to see that the shoe still had a foot in it.’ American soldiers soon found that the Germans prided themselves on their skills in this field. Roadblocks were booby-trapped, so the trunks dropped across trails as a barrier had to be towed away from a distance with long ropes. New arrivals had to learn about

‘Schu, Riegel, Teller and anti-tank mines’

. The Riegel mine was very hard to remove as it was ‘wired up to explode upon handling’. Germans laid mines in shellholes where green troops instinctively threw themselves when they came under fire. And well aware that American tactical doctrine urged troops to approach a hill whenever possible via ‘draws’, or gullies, the Germans made sure that they were mined and covered by machine-gun fire.

Both sides mined and counter-mined in a deadly game.

‘When mines are discovered,’

a report stated, ‘this same unit places its own mines around the enemy mines to trap inspecting parties. The Germans, in turn, are liable to booby-trap ours, and so on.’ A member of the 297th Engineer Combat Battalion noticed a mine poking through the surface of the ground. Fortunately for him, he was suspicious and did not go straight to it. A mine detector showed that the Germans had buried a circle of other mines all around it and he would have had a leg blown off.

‘The Germans are burying

mines as many as three deep in the soft muddy roads in this sector,’ Colonel Buck Lanham’s regiment reported soon after reaching the Hürtgen Forest. The engineers would locate and remove the top one, not realizing that there were more. Once spotted, they resorted to blowing them with dynamite and then repairing the hole in the road with a bulldozer.