Atlantis and the Silver City (28 page)

Read Atlantis and the Silver City Online

Authors: Peter Daughtrey

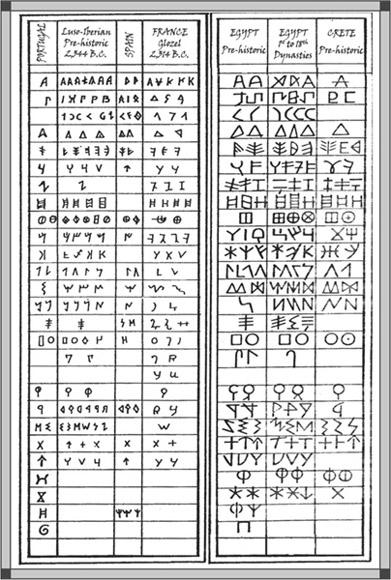

Academics refer to it as the “southwestern” script, acknowledging that it emanated from southwest Iberia where the most finds have been made

and where it appears to have been perpetuated the longest. Samples of a similar script called the “northeastern” exist elsewhere in Spain.

The dates originally attributed to some of these earliest discovered Algarve specimens go as far back as 2300

B.C.

Archaeological and academic circles have wrestled with the enigma these inscriptions present, and for a while have put forward a unified front. Because the script shares some characters with the Phoenician and Greek alphabets, rather than face the traumatic possibility that it might represent a source of writing that predated them—with the consequent need to completely redraft the history of the Western alphabet—academics have shoehorned it into accepted dogma: that the Algarve script must have developed from Phoenician and Greek influences in the region from about 900

B.C.

The samples unearthed must, they reason, therefore date from the late Iron Age, around 500 to 900

B.C.

(The Phoenician alphabet is thought to have emerged around 1050

B.C.

and the Greek to have developed from it sometime afterward.) On analysis, this date for the southwest script is clearly nonsense. Consider the following evidence.

First, there are several references by ancient Greek writers indicating that the Phoenicians did not invent their alphabet. The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who flourished between 60 and 30

B.C.

, wrote: “Men tell us … that the Phoenicians were not the first to make the discovery of letters; but that they did no more than change the form of the letters, whereupon the majority of mankind made use of the way of writing them as the Phoenicians devised.”

83

Tacitus, a Roman historian

(A.D.

56–117), wrote: “The Phoenicians gained the reputation of inventing a form of writing, which they merely received.”

84

The writings of the famous Greek Strabo (64

B.C.–A.D.

34)—known as “the Geographer”—which I have referred to in earlier chapters, are relevant. He said that the Turdetani peoples of southwest Iberia had a written script as long as six thousand years previously—an inconvenient and unwelcome statement dismissed by the establishment. “They are the most cultured of all the Iberians; they employ the art of writing and have written books containing memorials of ancient times, and also poems and laws set in verse, for which they claim an antiquity of six thousand years.”

85

If the script existed in 6500

B.C.

in a form that was in regular use, it would have taken some considerable time to develop. It may even have been inherited from an earlier epoch. We do not know where Strabo obtained his information, but it smacks of the truth. What did he have to gain by inventing it? His most likely source was Greek merchantmen trading with the Turdetani region along the southern Algarve and Spanish coasts and, like Plato and Solon before him, the Egyptians. Why have none of the books to which he refers survived? The most likely culprits were the merciless Carthaginians. If anything survived, then other Lusitanian tribes from north of the Algarve destroyed cities and their contents in the south in retribution for the Conii cooperation with the Romans. Other villains could have been the Romans themselves. Then, of course, we have to take into account the periodic disastrous quakes, followed by fires and tsunamis.

Fortunately, solid examples have survived: the

herouns

. The samples were mostly found in the mountains, in their foothills, or just north of them, well away from any coastal inundations and the destruction of cities. They were monuments, erected in private places for personal reasons.

A number of Portuguese historians have published books on the subject since 1983, but the expert is a local Algarve man: Carlos Alberto Basilio Castelo, an amateur epigrapher. He has spent decades and devoted much of his life to solving this enigma. He is now able to translate the script and can even trace its subtle evolution over millennia. This enables him to attribute an approximate date for each find, according to the engraving displayed. In his opinion, many of them definitely predate 1050

B.C.

and the Phoenicians. He may not be a professional academic, but his research is impeccable.

From the evidence Carlos has amassed, he is convinced that the script represents the remnants of a root language that, in the very ancient past, was taken to other countries, particularly to the Middle East, the Atlantic seaboard of Europe, and Morocco. Over the ages, it was developed by different peoples and changed, eventually finding its way back from the Middle East to the Algarve in an adapted form, via the Phoenicians. This explains why some of the characters remained the same.

Although I was familiar with Carlos Alberto’s work, having saved newspaper articles detailing it from before the turn of the millennium, I did not meet him until 2009, having already mapped out this book. When he courteously showed me into the study at his home, I was stunned. It was reminiscent of a set from such movies as

Raiders of the Lost Ark

, and I half expected Harrison Ford to stride through the door. The walls were covered in charts, made by Carlos, of the script and its derivatives. There were also crammed files as well as eclectic artifacts, including a bust of an Egyptian pharaoh. Carlos’s breadwinning career as a gifted graphic artist was evident from the general bric-a-brac.

He is currently working with other experts in northern Spain on a project tracing the history and spread of “The Royal People”: the ancient Kunii/Conii. There is much confusion and uncertainty about the various names given to these ancient people who lived in southwest Iberia, and many are probably interchangeable; the Conii, the Kunii, and the Turdetani are but a few. Carlos believes it was the Conii who perpetuated the script for many thousands of years. They were highly cultured and even had a religion worshipping just one god. They called him Elel or Eliel on some

herouns

, and the Old Testament’s “Eloim” uncannily echoes this. Which came first?

Like other investigators of ancient civilizations, he theorizes that those we regard as “previously uncivilized man” existing, say, five thousand years ago, were the result of the degeneration of a great civilization from many thousands of years earlier, which had been annihilated in a huge disaster. Those who survived had migrated far and wide to different parts of the world. I believe this is partially correct, but also that other parts of the globe—India and Southeast Asia, for example—had parallel civilizations existing at the same time as Atlantis. The old Egyptian priest had prefaced his words to Solon: “There have been, and will be again, many destructions of mankind arising out of many causes: the greatest have been brought about by agencies of fire and water and other lesser ones by innumerable other causes.”

Also, Plato comments in

Critias

: “In the days of old, the gods had the whole earth distributed among them by allotment.”

The following examples are from those meticulously filed in Carlos’s study, along with others I have been able to research.

Pre-10,600

B.C.

Carlos showed me an illustration of an engraving on a bone dagger dating way back to French prehistory.

86

I had seen it before. It is a celebrated archaeological find, but I had not realized its significance: it shows a pregnant wolf and the word

Laol

in the archaic alphabet. He maintains that this spelling was perpetuated by the Conii as

Laoba

or

Loba

and

Laobi

or

Lobo. Lobo

is still the Portuguese word for “wolf.” One of the Algarve’s most famous tourist and golfing developments is called

Vale de Lobo

(“Valley of the Wolf”). (

SEE IMAGE

39

BELOW

.)

(

IMAGE

39)

The bone dagger from the Stone Age, engraved with letters from the ancient alphabet and the depiction of a wolf (circled). Carlos Castelo maintains that the word shown meant “wolf” in the ancient Conii script and has evolved into the word used for wolf today in the Portuguese language: lobo

. (Courtesy of Carlos Castelo.)

4000

B.C.

One of Carlos’s charts shows characters from a famous dolmen at Alvão in central Portugal. This has been dated to around 4000

B.C.

Some of the characters on it again match the more recent Algarve examples.

4000

B.C.

In 1916, a piece of engraved stag bone was discovered at a place called Bancal Deta, near Coruna in the Galicia region of northern Spain, to the north of Portugal.

87

Archaeologists have scientifically dated it to between 3800 and 4000

B.C.

They described the engraved letters as belonging to an unknown Iberian pre-Indo-European language. I dug out the chart given to me by Carlos Alberto showing the Algarve letters and those used in predynastic Egypt. Most match the ones on the bone.

Using the Iberian script as a reference, experts have recently claimed to have translated the engraving as spelling “A TA LA TA R TE.”

88

If this is correct, it opens up a fascinating area for speculation. The name Tartessos, the ancient kingdom referred to in the Bible and possibly once ruled by King Arganthonius, could have been formed from a combination of TARTE and the Greek suffix ESSOS, or even NESSOS, meaning “peninsula.” ATALA is the ancient civilization referred to in a Moroccan Berber legend about a fabulous, verdant land to their north, which was destroyed a long time ago in a terrible catastrophe (see last chapter).

Could this piece of stag bone have been carved by refugees to assert their identity and as a reminder of their sunken homeland far to the south?

Pre-3000

B.C.

Way before 3000

B.C.

, the Egyptians had an alphabet script similar to the Algarvean one, prior to their development of hieroglyphics. Mummies have been found in Egypt with inscriptions formed using Iberian characters. In 1890, the famous Scottish archaeologist and ancient Egyptian historian William Flinders Petrie found examples on stone splinters dating from between 3000 and 12,000

B.C.

89

Apart from the timescale, preceding the great dynasties and way before the Phoenicians, this has another important significance relating to the Atlantis legend that will be covered later in this book. In support of the Egyptian connection, it should be mentioned that Manetho (250

B.C.

) wrote that the Egyptian script could be attributed to a western island and particularly their god Thoth, who had once ruled a “Western Domain.”

90

The Turin Papyrus (1700

B.C.

) has Thoth listed as one of the ten kings from the “reign of the gods” around twelve thousand years earlier.

91

(

SEE IMAGES

40

A AND

40

B ON THE FOLLOWING PAGES

.)

(

IMAGE

40

A

)