Atlantis and the Silver City (32 page)

Read Atlantis and the Silver City Online

Authors: Peter Daughtrey

There is a report that Moses’s father-in-law was the head of the Kenites, a group that joined with Moses’s Israelites. An alternative name, frequently used in ancient reports, for the Conii/Kunii people from the Algarve was the Cynetes or Kynetes.

The Tribe of Dan—or Dana—was also reported to have worshipped the goddess Diana, also a well-known Greek deity. The large river that forms the border between the Algarve and Spain, now called the Guadiana, used to be known as the Ana. I have read that the whole region was once known as the country of Ana (D’Ana?).

If all this is confusing, I apologize. I have tried to pull together many, many strands that cover thousands of years. Modern genetic research, such as that involving DNA and Haplogroup X, is undoubtedly helping to

unravel the tangled web and indicates that the various dispersals of people discussed here are broadly correct.

No matter how complicated the path all these blonds or red-haired people took, however, if we could follow them back it is likely they would all lead to southwest Iberia and Atlantis.

So, do you carry the Atlantean gene this hypothesis about hair color would indicate? If you have blond/red hair, or any of the shades in between, then you probably do. No matter where you now live, somewhere in the ancient past, one of your ancestors with these unique distinguishing features probably struck out from Atlantis. Welcome to the club.

This book started with that huge stone egg. I have not revisited it so far as, in itself, it did not provide any evidence to prove that Atlantis was in Iberia. Now, with Atlantis firmly nailed down, I decided that it was time to further research this extraordinary object. Might it be the first relic ever found to support Plato’s legend?

CHAPTER NINETEEN

The Great White Egg

She had deliberately chosen this very night. The old woman had said it would be auspicious for her mission. The full moon created an eerie combination of flat light and deep shadows

.

She drifted up the gentle slope past the houses, with their slumbering occupants, and the almond trees, with the perfume from their delicate white blossom hanging heavily in the air, until the monument suddenly loomed stark on the skyline, its glistening, white surface beckoning. Willing herself not to recoil against the chill surface, she loosened the robe and pressed her naked body to the stone. She moved gently, massaging against the strange symbol sculpted onto it, her arms widespread in a fervent embrace. She ached for a child but, after several years with her man, pregnancy still eluded her. Now she fervently prayed to the gods to make her fertile

.

The old woman had said that this great white egg, representing the very essence of birth, had worked its magic in the past. Why not for her?

It was powerful. Legend had it that the gods erected it long ago to mark the begining.

T

hat’s not a recorded event, but one that I suspect could well have happened quite regularly many thousands of years ago. The stone egg still exists, having survived every calamity the Algarve’s torrid history could

throw at it. As recounted in the first chapter, it has been lying unappreciated for some thirty years in a corner of a delightful museum in Lagos, an old coastal town famous as a port for many of Henry the Navigator’s caravels that sailed forth to discover uncharted parts of the world. If this book’s hypothesis for Atlantis is correct, then this object could be highly significant.

The museum houses an eclectic variety of remains from the Neolithic, Roman, and Moorish periods, together with ethnic examples from life in the area during the last few centuries. The largest object there, the stone egg, is not from Lagos but from land near Silves. I knew the general area where it had been found, but not the exact position. The museum could not help, nor could the local archaeology department; but a spot of amateur sleuthing eventually enabled me to track down one of the local men involved in the discovery. He obligingly took me to the very place. To my amazement, it was overlooking the area I have already suggested was the port for Plato’s Atlantis capital, ancient Silves. He had helped unearth it three decades before, when the land was being prepared for agriculture. A new well was being dug when, at a depth of between four and five meters, the workmen hit the top of a huge, curved, smooth rock. At first they thought it was the back of a carved stone pig, but, as the sides were excavated, it became obvious that it was a large egg. Together, the workmen succeeded in hauling it to the surface with ropes. I had originally been told of its existence more than twenty years ago by an eyewitness who had seen it lying by the side of the road before being moved to its new home in Lagos (Silves did not then have a suitable museum to accommodate it).

The Lagos museum describes it as a

menhir

(standing stone), but I believe it is too sophisticated for that and was designed for another specific purpose—although it could have served as a

menhir

later in its life, as suggested in the opening cameo of this chapter. It is made from local limestone—the same white stone that Plato indicated was among those used extensively in the Atlantis citadel and which is freely available very close to where the relic was found.

It has been sculpted to represent a large egg, about six feet in height—or length. Unfortunately the side it lies on in the museum has been broken

either during its discovery or, more likely, at some stage when it was toppled over from wherever it was erected.

Sculpted down the three visible sides of the egg is the same large motif. The images stand proud of the surface, indicating that great care had been taken in the stone’s preparation, especially if the workers had only stone tools. It would have been far easier to finish the whole surface, then carve the images into it. (

SEE IMAGES

44, 45,

AND

46

IN THE PHOTO INSERT

.)

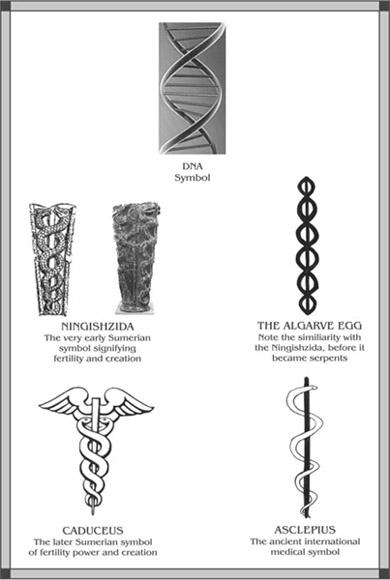

What could the motif possibly mean, or represent? It immediately struck me that it had an astonishing resemblance to the DNA helix but, before jumping to sensational conclusions, further research was called for.

Carlos Castelo informed me that each segment of the motif was identical to the fertility symbol of the Kunii people, assumed to have been adopted because of its similarity to the female vulva. It would, however, be illogical to stack a whole pile of segments on top of one another. That would be confusing. One symbol standing alone is more easily recognizable and has greater impact.

The similarity to the DNA helix is masked by a central rod. Is it possible, though, that there are two elements combined? One element could be the central rod or wand, and the other a simplified version of the DNA helix to make it possible to carve it on stone.

Throughout ancient history, the rod has represented power, the staff of office, the scepter of kings and queens. Historical records are littered with other references, including:

• Author Zecharia Sitchin, an expert on ancient Sumerian tablets, believed that the rod or wand traditionally represented “the Lord of the manufacture” or “implement of life.”

• Ancient Egyptian priests were depicted with rods.

• Stone Age paintings show figures holding rods, thought to be symbolic of power.

• Moses had a wand—as did his brother Aaron—that supposedly had magical powers.

• Druids had a wand that represented “the tool and vehicle of the power of the heavens.”

• Some scholars believe the rod has roots as a phallus—always a good fallback for bemused experts.

In 1910, archaeologist Dr. William Hayes Ward wrote that he thought a well-known symbol called the caduceus had originated in Sumeria between 3000 and 4000

B.C.

The oldest known example is on a Sumerian cylinder seal. This is uncannily similar to the carving on the Algarve “egg.” It depicts two snakes coiling up the rod and is sometimes shown with wings at the top. (

SEE IMAGE

43

BELOW

.)

(

IMAGE

43)

Chart depicting the DNA symbol, the carving on the stone egg, and other similar symbols of ancient Sumerian origin dating from between 4,000 and 2,000 B.C

.

It is unclear exactly what the caduceus originally represented or stood for, but the most widely accepted explanation is that it was a symbol of fertility and wisdom. Later, the Greeks associated it with their god Hermes (or Mercury), who was known as “the messenger of the gods.” Among his more dubious credentials, Hermes was the god of thieves, but he was also the protector of merchants. I suppose the latter would have been apt for a monument overlooking a bustling harbor front devoted to trade, although there are no wings or snakes on the Algarve stone. He is also thought to have been the Greek equivalent of the Egyptian god Thoth, who originally ruled in the West.

The caduceus has also become confused with another ancient motif, the asclepius, which shows a single snake around a rod and was the original medical symbol. Confusion still reigns, with the caduceus wrongly appearing on the badge of the American medical corps.

Yet another similar symbol predates the caduceus by about a thousand years: the Ningishzida. It represented a Mesopotamian deity who was the god of nature and fertility.

That the symbol on the egg appears to have evolved into something slightly different in Sumeria but still stood for fertility and wisdom supports the DNA hypothesis. The gods/rulers who influenced the founding of the Sumerian civilization were known as the “serpent people.” If they introduced the symbol into Sumeria, it’s easy to see how it could have evolved into two intertwining serpents. The Sumerians were not the only ones to depict versions of it; an intertwined snake version appears on frescoes on the tombs of Egyptian pharaohs Seti and Rameses VI.

The age of the Algarve “egg” is critical here. It is thought that the many

menhirs

and assorted standing stones scattered around the Algarve date from around 3500 to 2500

B.C.

As mentioned in the last chapter, the established view is that the Kunii people migrated from the northeast to the Algarve after that period. Carlos Castelo, supported by the latest genetic research, might disagree; but if that is correct, and the “egg” dates back as far as the other

menhirs

—to around 3500

B.C.

—then the original symbol could not have come with the Kunii. They must have extracted just one segment from the egg’s carving, knowing that it was locally associated with fertility and because of its unmistakable similarity to the female vulva.

I strongly suspect, however, that the stone egg is even older. It was found at a depth of between four and five meters, in arable land at the brow of a hill. It is unlikely that soil would have been naturally washed down onto it: the opposite is far more likely.

In their book

Uriel’s Machine

, Robert Lomas and Christopher Knight detailed a strong scientific case for Noah’s great flood occurring in 7640

B.C.

100

This also concords with the last great glacier melt. Apart from the host of worldwide legends, the evidence is supported by research. The measurable results point to the cause being a large ice meteorite breaking into pieces and plunging into the oceans around the world. Large chunks of the ozone layer would have been destroyed, leading to an increase in the production of carbon-14. Nitric acid would have been formed by nitrogen being burned by the sheer energy of the impact. This has been measured in worldwide ice cores, demonstrating that an event of this magnitude happened in about 7640

B.C.

That some ten thousand species became extinct around that time is strong supporting evidence.

The inevitable result would have been gigantic tsunamis crashing over all the world’s landmasses at speeds of around 640 miles per hour. Even worse, their height would have reached five kilometers. Only those on the highest mountains or hundreds of miles from any coast could have survived the initial calamity. The equivalent of a nuclear winter would have followed, with the sun blotted out in most areas. There would also have been unprecedented deluges of rain.

Colossal amounts of mud, rock, and debris would have been tossed around before being dragged back out to sea or deposited on land as the waters subsided. The world’s great saltwater lakes—the Dead Sea and that in Utah, for example—would have been formed as the ocean water remained trapped in large valleys.

The many

menhirs

that can still be seen all over the western Algarve are, almost certainly, still in their original standing positions. They must, therefore, have been erected since this flood, otherwise they would have been flattened and buried. Archaeologists concur in dating them back to between 3500 and 2500

B.C.

The great egg, however, was buried under thirteen to sixteen feet of soil. It is tempting to presume

that this was a result of this last great flood. It must have been buried sufficiently deep to have disappeared. If it had just lain toppled on the ground and even partly visible for centuries, its significance would almost certainly have led to any superstitious new populace reerecting it to an upright position.