B0041VYHGW EBOK (167 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

11.23 … and Pino chases him away.

Cinematic technique frequently emphasizes the community as a whole. Indeed, one reason the film has so many segments is that there are frequent cuts from one action to another. The narration is largely unrestricted, flitting from one group of characters to another, seldom lingering with any individual. Similarly, complex camera movements follow characters through the street, catching glimpses of other activities going on in the background. Other camera movements slide away from one line of action to another. On the morning after the riot, Da Mayor wakes up in Mother Sister’s apartment and the camera shifts to Mookie

(

11.24

–

11.26

).

11.24 Da Mayor and Mother Sister talk and then move out into her front room, the camera tracking with them and …

11.25 … passing through the window as they reach it, craning down …

11.26 … to a close view of Mookie, on the way to the pizzeria.

The dense sound track helps characterize the community. As Mookie walks past a row of houses, the sounds of radios tuned to different stations fade up and down, hinting at the offscreen presence of the inhabitants. The music broadcast by the DJ plays a large role in drawing the many brief scenes together, with the same song carrying over various exchanges of dialogue. The different ethnic groups are characterized by the types of music they listen to.

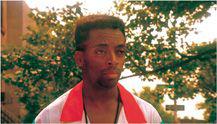

Style also stresses the underlying problems in the community. Radio Raheem’s threatening demeanor is emphasized in some scenes by his direct address into a wide-angle lens

(

11.27

).

Mookie’s self-absorption and lack of interest in the neighborhood is suggested in a visual motif of high-angle views showing him stepping unheedingly on a cheerful chalk picture of a house that a little girl is drawing on the pavement

(

11.28

).

Sound contributes to the racial tensions, as in the scenes where Radio Raheem annoys people by playing his rap song at high volume.

11.27 Radio Raheem orders a slice of pizza from Sal, who has ordered him to turn his radio off.

11.28 One shot from a motif of Mookie walking across a chalk drawing.

Do The Right Thing,

despite its stretching of traditional Hollywood conventions, remains a good example of a contemporary approach to classical filmmaking. Its style reflects the looser techniques that became conventions of post-1960s cinema—an era when the impact of television and European art films inspired filmmakers to incorporate somewhat more variety into the Hollywood system. Even the plot’s departures from tradition are somewhat motivated because Lee adopts the basic purpose of the social problem film—to make us think and to stir debate.

Breathless (À Bout de souffle)

1960. Les Films Georges de Beauregard, Impéria Films and Société Nouvelle de Cinéma. Directed by Jean-Luc Godard. Story outline by François Truffaut, dialogue by Godard. Photographed by Raoul Coutard. Edited by Cécile Decugis. Music by Martial Solal. With Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean Seberg, Daniel Boulanger, Henri-Jacques Huet, Van Doude, Jean-Pierre Melville.

In some ways,

Breathless

imitates a 1940s Hollywood staple, the

film noir

, or “dark film.” Such films dealt with hard-boiled detectives, gangsters, or ordinary people tempted into crime. Often a seductive femme fatale lured the protagonist into a dangerous scheme for hidden purposes of her own (for example,

The Maltese Falcon

and

Double Indemnity

).

Breathless

’s plot links it to a common noir vehicle—the outlaw movie involving young criminals on the run (such as

They Live by Night

and

Gun Crazy

).

The bare-bones story could serve as the basis of a Hollywood script. A car thief, Michel, kills a motorcycle cop and flees to Paris in order to get money to escape to Italy. He also tries to convince Patricia, an American art student and aspiring writer with whom he had a brief affair, to go with him. After equivocating for nearly two days, she agrees. Just as Michel is about to receive the cash he needs, Patricia calls the police, and they kill him.

Yet Godard’s presentation of this story could never pass for a polished studio product. For one thing, Michel’s behavior is presented as driven

by

the very movies that

Breathless

imitates. He rubs his thumb across his lips in imitation of his idol Humphrey Bogart. Yet he is a petty thief whose life spins out of control. He can only fantasize himself as a romantic Hollywood tough guy.

The film’s ambivalent attitude toward classical Hollywood cinema also pervades form and technique. As we’ve seen, the norms of classical style and storytelling promote narrative clarity and unity. In contrast,

Breathless

appears awkward and casual, almost amateurish. It makes character motivations ambiguous and lingers over incidental dialogue. Its editing jumps about frenetically. And, whereas films noirs were made largely in the studio, where selective lighting could swathe the characters in a brooding atmosphere,

Breathless

utilizes location shooting with available lighting.

These strategies make Michel’s story quirky, uncertain, and deglamorized. They also ask the audience to enjoy the film’s rough-edged reworking of Hollywood formulas. An opening title dedicates the film to Monogram Pictures, a Poverty Row studio that churned out B-movies. The title seems to announce a film that is indebted to Hollywood but not wholly bound by its norms.

Like many protagonists in classical Hollywood films, Michel has two main goals. In order to leave France, he must search for his friend Antonio, the only one who can cash a check for him. He also hopes to persuade Patricia to go with him, and it becomes apparent as the action progresses that, despite his flippant attitude, his love for her outweighs his desire to escape.

In a classical film, these goals would drive the action along fairly steadily. Yet in

Breathless,

the plot moves in fits and starts. Brief scenes—some largely unconnected to the goals—alternate with long stretches of seemingly irrelevant dialogue. Most of

Breathless

’s 22 separate segments run four minutes or less. One 43-second scene consists simply of Michel pausing in front of a theater and looking at a picture of Bogart.

Scenes containing crucial action are sometimes brief and confusing. The murder of the traffic cop, an event that triggers much of what follows, is handled in a very elliptical fashion. In long shot, we see the officer approaching Michel’s car, parked in a side road. In medium long shot, Michel reaches into the car for the gun. A close shot of his head follows, as the cop’s voice is heard saying, “Don’t move or I’ll drill you”

(

11.29

).

Two very brief close-ups pan along Michel’s arm and along the gun

(

11.30

,

11.31

),

with the sound of a gunshot. We then get a glimpse of the cop falling into some underbrush

(

11.32

),

followed by an extreme long shot of Michel, running far across a field. So much action has been left out that we can barely comprehend what is happening, let alone judge whether Michel shot deliberately or by accident.

11.29 In

Breathless

’s murder scene, brief shots …