B0041VYHGW EBOK (163 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

The restriction of the action to very few locales might seem a handicap, but the patterns of character placement are remarkably varied and functional. Walter’s persuading Hildy to write the story is interesting from this standpoint (

11.1

,

11.2

; note the gestures). And spatial continuity in the editing anticipates each dramatic point by judiciously cutting to a closer shot or smoothly matching on action so that we watch the movements and not the cuts

(

11.3

,

11.4

).

The change in the position of Walter’s arms, so apparent in our illustrations, goes unnoticed because of Hildy’s broader and more emphatic gestures. Virtually every scene, especially the restaurant episode and the final scene, offers many fine examples of classical continuity editing. In all, space is used to delineate the flow of the cause–effect sequence.

11.1 In

His Girl Friday,

as Walter and Hildy pace in a complete circuit around the desk …

11.2 … Walter assumes dynamic and comic postures.

11.3 In the opening scene of

His Girl Friday,

Hildy’s action of throwing her purse at Walter …

11.4 … is matched at the cut to a more distant framing.

We might highlight for special attention one specific item of both sound and mise-en-scene. It is plausible that newspapermen in 1939 use telephones, but

His Girl Friday

makes the phone integral to the narrative. Walter’s duplicity demands phones. At the restaurant, he pretends to be summoned away to a call; he makes and breaks promises to Hildy via phones; he directs Duffy and other minions by phone. More generally, the pressroom is equipped with a veritable flotilla of phones, enabling the reporters to contact their editors. And, of course, Bruce keeps calling Hildy from the various police stations in which he continually finds himself. The telephones thus constitute a communications network that permits the narrative to be relayed from point to point.

But Hawks also visually and sonically orchestrates the characters’ use of the phones. There are many variations. One person may be talking on the phone, or several may be talking in turn on different phones, or several may be talking at once on different phones, or a phone conversation may be juxtaposed with a conversation elsewhere in the room. In scene 11, there is a polyphonic effect of reporters coming in to phone their editors, each conversation overlapping with the preceding one. Later, in scene 13, while Hildy frantically phones hospitals, Walter screams into another phone

(

11.5

).

And when Bruce returns for Hildy, a helter-skelter din arises that eventually sorts itself into three sonic lines: Bruce begging Hildy to listen, Hildy obsessively typing her story, and Walter yelling into the phone for Duffy to clear page one (“No, no, leave the rooster story—that’s human interest!”). Like much in

His Girl Friday,

the telephones warrant close study for the complex and various ways in which they are integrated into the narrative, and for their contribution to the rapid tempo of the film.

11.5

His Girl Friday.

1959. MGM. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Script by Ernest Lehman. Photographed by Robert Burks. Edited by George Tomasini. Music composed by Bernard Herrmann. With Cary Grant, Eva Marie Saint, James Mason, Leo G. Carroll, Jesse Royce Landis.

Hitchcock long insisted that he made thrillers, not mystery films. For him, creating a puzzle was less important than generating suspense and surprise. While there are important mystery elements in films such as

Notorious

(1946),

Stage Fright

(1950), and

Psycho

(1960),

North by Northwest

stands as almost a pure example of Hitchcock’s belief that the mystery element can serve as merely a pretext for intriguing the audience. The film’s tight causal unity enables Hitchcock to create an engrossing plot that fulfills the norms of classical filmmaking. This plot is presented through a narration that continually emphasizes suspense and surprise. (For more on thrillers, see

pp. 332

–334.)

Like most spy films,

North by Northwest

has a complex plot, involving two major lines of action. In one line, a gang of spies mistakes advertising agency executive Roger Thornhill for an American agent, George Kaplan. Although the spies fail to kill him, he becomes the chief suspect in a murder that the gang commits. He must flee the police while trying to track down the real George Kaplan. Unfortunately, Kaplan does not exist; he is only a decoy invented by the United States Intelligence Agency (USIA). Thornhill’s pursuit of Kaplan leads to the second line of action: his meeting and falling in love with Eve Kendall, who is really the mistress of Philip Van Damm, the spies’ leader. The spy-chase line and the romance line further connect when Thornhill learns that Eve is actually a double agent, secretly working for the USIA. He must then rescue her from Van Damm, who has discovered her identity and has resolved to kill her. In the course of all this, Thornhill also discovers that the spies are smuggling government secrets out of the country in pieces of sculpture.

“He (Hitchcock) was fairly universal, he made people shiver everywhere. And he made thrillers that are also equivalent to works of literature.”

— Jean-Luc Godard, director,

Breathless

From even so bare an outline, it should be evident that the film’s plot presents many conventional patterns to the viewer. There’s the search pattern, seen when Thornhill sets out to find Kaplan. There’s also a journey pattern: Thornhill and his pursuers travel from New York to Chicago and then to Rapid City, South Dakota, with side excursions as well. In addition, the last two-thirds of the plot is organized around the romance between Thornhill and Eve. Moreover, each pattern develops markedly in the course of the film. In the course of his search, Thornhill must often assume the identity of the man he is trailing. The journey pattern gets varied by all the vehicles Thornhill uses—cabs, train, pickup truck, police car, bus, ambulance, and airplane.

Most subtly, the romance line of action is constantly modified by Thornhill’s changing awareness of the situation. Believing that Eve wants to help him, he falls in love with her. But then he learns that she sent him to the murderous appointment at Prairie Stop, and he becomes cold and suspicious. When he discovers her at the auction with Van Damm, his anger and bitterness impel him to humiliate her and make Van Damm doubt her loyalty. Only after the USIA chief, the “Professor,” tells him that she is really an agent does Thornhill realize that he has misjudged and endangered her. Each step in his growing awareness alters his romantic relation to Eve.

This intricate plot is unified and made comprehensible by other familiar strategies.

North by Northwest

has a strict time scheme, comprising four days and nights (followed by a brief epilogue on a later night). The first day and a half take place in New York; the second night on the train to Chicago; the third day in Chicago and at Prairie Stop; and the fourth day at Mount Rushmore. The timetable is neatly established early in the film. Van Damm, having abducted Roger as Kaplan, announces, “In two days you’re due at the Ambassador East in Chicago, and then at the Sheraton Johnson Hotel in Rapid City, South Dakota.” This itinerary prepares the spectator for the shifts in action that will occur in the rest of the film. Apart from the time scheme, the film also unifies itself through the characterization of Thornhill. He is initially presented as a resourceful liar when he steals a cab from another pedestrian. Later, he will have to lie in many circumstances to evade capture. Similarly, Roger is established as a heavy drinker, and his ability to hold his liquor will enable him to survive Van Damm’s attempt to force him to kill himself when driving while drunk.

A great many motifs are repeated and help make the film cohere. Roger is constantly in danger from heights: his car hangs over a cliff; he must sneak out on the ledge of a hospital; he has to clamber up Van Damm’s modernistic clifftop house; and he and Eve wind up dangling from the faces on Mount Rushmore. Thornhill’s constant changing of vehicles also constitutes a motif that Hitchcock varies. A subtler example is the motif that conveys Thornhill’s growing suspicion of Eve

(

11.6

,

11.7

).

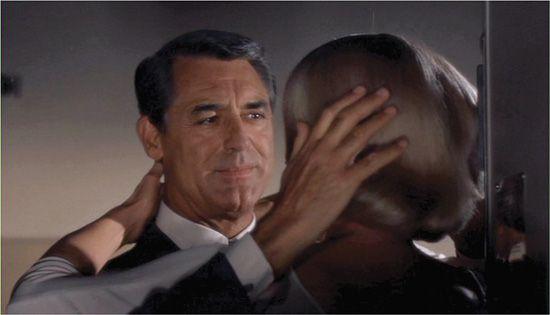

11.6 On the train, when Thornhill and Eve kiss, his hands close tenderly around her hair, but …