B0041VYHGW EBOK (165 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

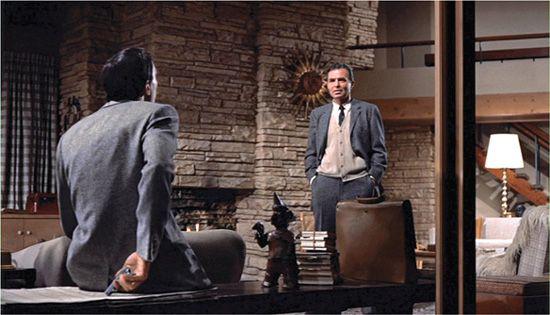

11.13 … as Leonard betrays Eve to Van Damm.

11.14 When Van Damm reacts by punching Leonard, he is seen from Leonard’s POV …

11.15 … and then Leonard is seen from his POV.

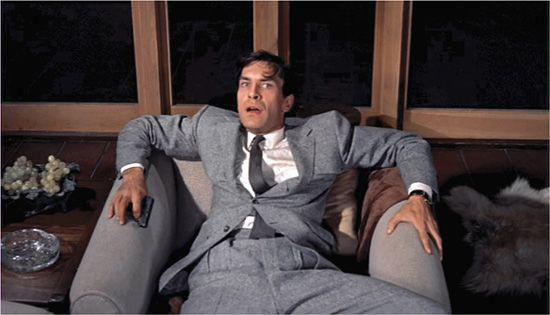

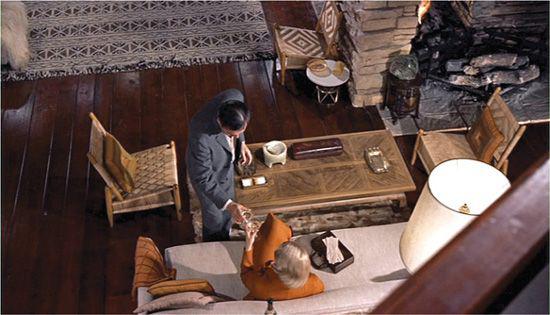

The second phase of the sequence can be said to begin when Roger enters Eve’s bedroom. She has gone back downstairs and is sitting on a couch. Again, Hitchcock emphasizes the restriction to Thornhill’s knowledge by means of optical POV shots

(

11.16

,

11.17

).

In order to warn Eve, he uses his ROT monogrammed matchbook (a motif set up on the train as a joke). He tosses the matchbook down toward Eve. This initiates still more suspense when Leonard sees it, but he unconcernedly puts it in an ashtray on the coffee table. When Eve notices the matchbook, Hitchcock varies his handling of optical POV from the first subsegment. There he was willing to show us the face-off between Van Damm and Leonard (

11.14

,

11.15

). Now he does not show us Eve’s eyes at all. Instead, through Roger’s eyes, we see her back stiffen; we

infer

that she is looking at the matchbook

(

11.18

).

Again, though, Roger’s range of knowledge is the broadest, and his optical POV encloses another character’s experience. On a pretext, Eve returns to her room, and Roger warns her not to get on the plane.

11.16 Later, Thornhill’s glance down at the living room is followed by …

11.17 … a high-angle POV framing appropriate to his position on the balcony upstairs.

11.18 When Eve notices the matchbook, she is seen from Thornhill’s viewpoint upstairs.

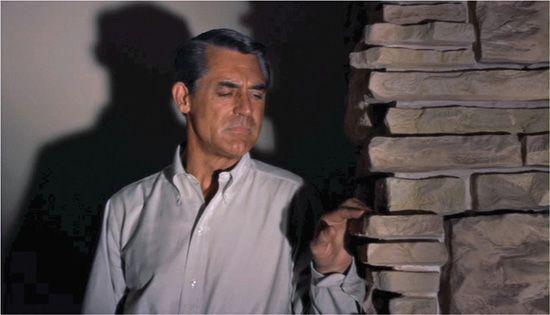

As the spies make their way to the landing field outside, Roger starts to follow. Now Hitchcock’s narration shifts again to show Van Damm’s housekeeper spotting Roger’s reflection in a television set. As earlier in the film, we know more than Roger does, and this generates suspense when she walks out … and returns with a pistol aimed at him.

The third section of the climax takes place outdoors. Eve is about to get in the plane when a pistol shot distracts the spies’ attention long enough for her to grab the statuette and race to the car Roger has stolen. This portion of the sequence confines us to Eve’s range of knowledge, accentuating it with shots from her optical POV. The pattern of surprise interrupting a period of suspense—here, Roger’s escape from the house interrupting Eve’s tense walk to the plane—will dominate the rest of the sequence.

“In

North by Northwest

during the scene on Mount Rushmore I wanted Cary Grant to hide in Lincoln’s nostril and have a fit of sneezing. The Parks Commission of the Department of Interior was rather upset at this thought. I argued until one of their number asked me how I would like it if they had Lincoln play the scene in Cary Grant’s nose. I saw their point at once.”— Alfred Hitchcock, director

There follows a chase across the presidents’ faces on Mount Rushmore. Some crosscutting informs us of the spies’ progress in following the couple, but on the whole, the narration restricts us to what Eve and Thornhill know. As usual, some moments are heightened by optical POV shots, as when Eve watches Roger and Valerian roll down what seems to be a sheer drop. At the climax, Eve is dangling over the edge while Roger is clutching one of her hands and Leonard grinds his foot into Roger’s other hand. It is a classic, not to say clichéd, situation of suspense. Again, however, the narration reveals the limits of our knowledge. A rifle shot cracks out and Leonard falls to the ground. The Professor has arrived and captured Van Damm, and a marksman has shot Leonard. Once more, a restricted range of knowledge has enabled the narration to spring a surprise on the audience.

The same effect gets magnified at the very end. In a series of optical POV shots, Roger pulls Eve up from the brink. But this gesture is made continuous, in both sound and image, with that of him pulling her up to a train bunk. The narration ignores the details of their rescue in order to cut short the suspense of Eve’s plight. Such a self-conscious transition is not completely out of place in a film that has taken time for offhand jokes. (During the opening credits, Hitchcock himself is shown being shut out of a bus. As Roger strides into the Plaza Hotel, about to be plunged into his adventure, the Muzak is playing “It’s a Most Unusual Day.”) This concluding twist shows once again that Hitchcock’s moment-by-moment manipulation of our knowledge yields a constantly shifting play between the probable and the unexpected, between suspense and surprise.

1989. Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks (distributed by Universal). Directed and scripted by Spike Lee. Photographed by Ernest Dickerson. Edited by Barry Alexander Brown. Music by Bill Lee et al. With Danny Aiello, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Giancarlo Esposito, Spike Lee, Bill Nunn, John Turturro, Rosie Perez.

At first viewing, Spike Lee’s

Do The Right Thing,

with its many brief, disconnected scenes, restlessly wandering camera, and large number of characters without goals might not seem a classical narrative film. And, indeed, in some ways, it does depart from classical usage. Yet it has the redundantly clear action and strong forward impetus that we associate with classical filmmaking. It also fits into a familiar genre of American cinema—the social problem film. Moreover, closer analysis reveals that Lee has also drawn on many traits of classicism to give an underlying unity to this apparently loosely constructed plot.

Do The Right Thing

takes place in the predominantly African-American Bedford–Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn during a heat wave. Sexual and racial tensions rise as Mookie, an irresponsible pizza delivery man, tries to get along with his Puerto Rican girlfriend, Tina, and with his Italian American boss, Sal. An elderly drunk, Da Mayor, sets out to ingratiate himself with his sharp-tongued neighbor, Mother Sister. An escalating quarrel between Sal and two customers, Buggin’ Out and Radio Raheem, leads to a fight in which Radio Raheem is killed by police. A riot ensues, and Sal’s pizzeria is burned.

Do The Right Thing

has many more individual sequences than, say,

His Girl Friday,

with its neatly delineated 13 scenes (

pp. 397

–398). Even lumping together some of the very briefest scenes, there are at least 42 segments. Laying out a detailed segmentation of

Do The Right Thing

might be useful for another analysis, but here we want to concentrate on how Lee weaves his many scenes into a whole.

One important means of unifying the film is its setting. The entire narrative is played out on one block in Bedford–Stuyvesant. Sal’s Famous Pizzeria and the Korean market opposite create a spatial anchor at one end of the block, and much of the action takes place there. Other scenes are played out in or in front of the brownstone buildings that line most of the rest of the street. Encounters among members of this neighborhood provide the causality for the narrative.

To match the limited setting, the action takes place in a restricted time frame—from one morning to the next. Structuring a film around a brief slice of the life of a group of characters is rare but not unknown in American filmmaking, as with

Street Scene, Dead End, American Graffiti, Nashville,

and

Magnolia.

The radio DJ Mister Señor Love Daddy provides a running motif that also binds the film’s events together. He appears in close-up in the first shot of the opening scene, and this initial broadcast provides important information about the setting and the weather—a heat wave that intensifies the characters’ tensions and contributes to the final violent outbreak. As the DJ speaks, the camera tracks slowly out and cranes up to reveal the street, still empty in the early morning. At intervals throughout the film, Mister Señor Love Daddy also provides commentary on the action, as when he tells a group of characters spewing racist diatribes to “chill out.” The music he plays creates sound bridges between otherwise unconnected scenes, since the radios in different locations are often tuned to his station. The end of the film echoes the beginning, as the camera tracks with Mookie in the street and we hear the DJ’s voice giving a similar spiel to the one on the previous morning, then dedicating the final song to the dead Radio Raheem.