B005GEZ23A EBOK

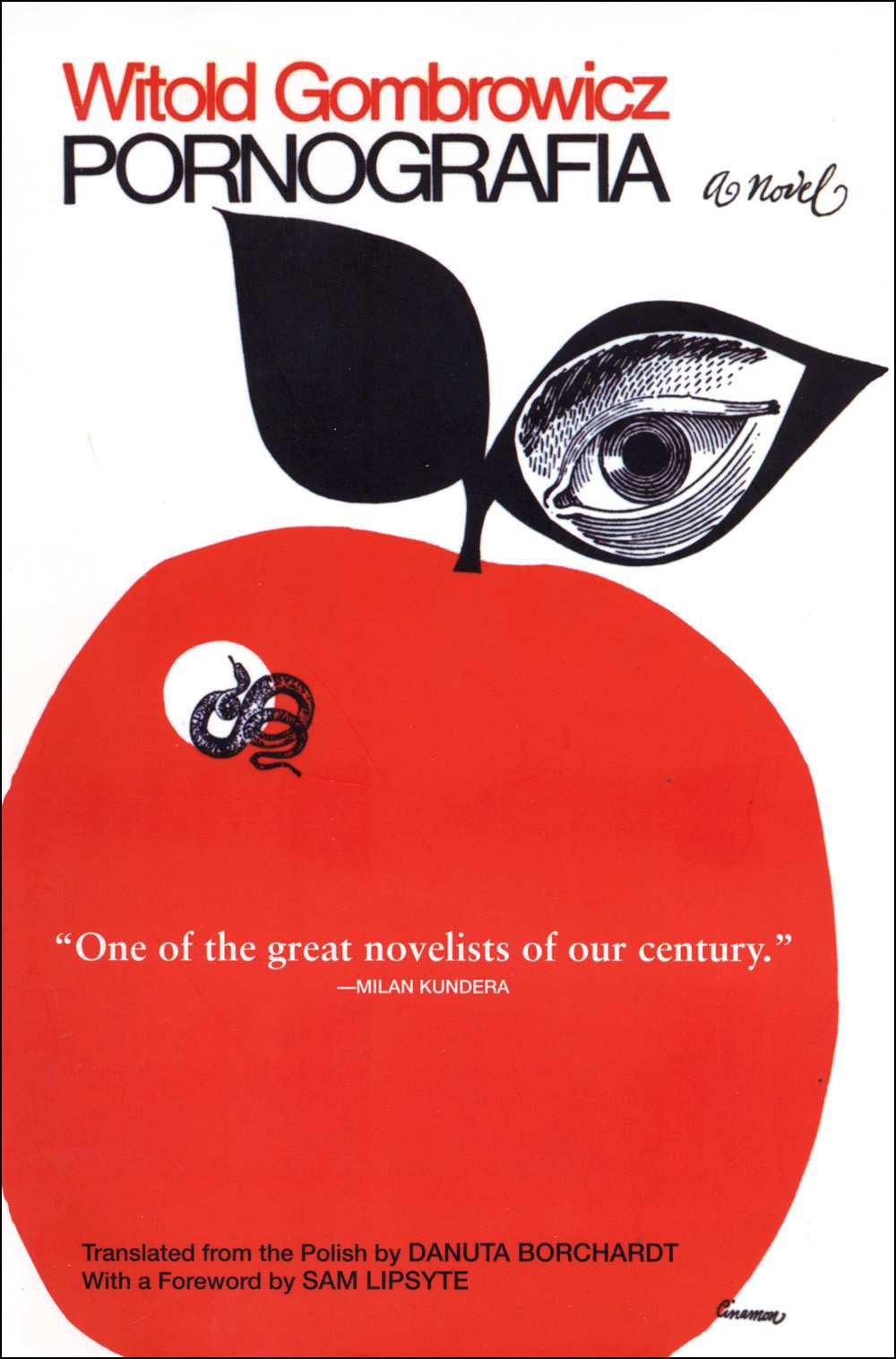

Authors: Witold Gombrowicz

PORNOGRAFIA

Other Works by Witold Gombrowicz

Ferdydurke

Cosmos

Trans-Atlantyk

Possessed

A Guide to Philosophy in Six Hours and Fifteen Minutes

Bacacay

A Kind of Testament

Diary

Polish Memories

Marriage

Ivona, Princess Burgunda

Operetta

Witold Gombrowicz

Translated from the Polish

by

Danuta Borchardt

Copyright © 1966 by Witold Gombrowicz

Translation copyright © 2009 by Danuta Borchardt

Foreword copyright © 2009 by Sam Lipsyte

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected]

Originally published in the Polish language by Instytut Literacki (Kultura) in Paris, France, under the title

Pornografia,

copyright © 1960.

First Grove Press edition published in 1978, together with

Ferdydurke.

Published simultaneaously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9528-9

| This publication has been funded by the |

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

by Sam Lipsyte

The story sounds like the set-up for a very dark joke. It is 1939, the eve of Hitler’s invasion of Poland. Somewhat oblivious to the coming catastrophe (like most everyone else), a writer from Warsaw accepts an invitation for an ocean cruise to South America. He’ll be back in a few months, refreshed for his next project. But once he sets sail there is a slight problem with his itinerary: World War Two. Trapped in Buenos Aires with little money and no Spanish, the writer forges a life there for over two decades. Though he eventually returns to Europe, he never sees Poland, the country that formed (and infuriated) him, again.

Such was the odd fate of Witold Gombrowicz, one of the major writers of the modern age, though readers in the United States have not heard enough about him. International acclaim came late to Gombrowicz, with the French translation of his first published novel,

Ferdydurke

(1937). This masterpiece takes on more than a few literary forms in its hilarious skewering of European philosophy, cultural upheaval, and generational

struggle. It remains one of the funniest books of an unfunny century.

Pornografia

(1960), published over twenty years later, mirrors many of the earlier novel’s themes, but in many ways it is a strikingly different work from

Ferdydurke.

It is also possibly a better one, tauter, its contents under more ferocious pressure, its savagery and comedy more directed. Narrated by a delightfully disturbing and nuanced man named (why not?) Witold Gombrowicz,

Pornografia

embraces an array of corrosive conflicts, between boys and girls, children and grown-ups, anarchy and the law, inferiority (life) and superiority (death), and competing versions of the real. (When the categories begin to deform and melt together, of course, things get truly, intriguingly, dicey.) Another opposition thrown into the pot is war and, if not peace, then a maddening state of not-yet-war. The latter seems especially important because

Pornografia

is set in a relatively calm pocket of Nazi-ravaged Poland, a place Gombrowicz never knew, and its plot consists of the erotic manipulations of a pair of would-be resistance fighters upon some increasingly witting farm teens. If that sounds like the makings of a gleefully tasteless farce, it might be because on a certain diabolical level

Pornografia

is one.

But it is also a profound behavioral study, though Gombrowicz eschews the staid tactics of some literary traditions, whose human specimens writhe under pins of omniscience. Here the psychology—the observations, projections, paradoxes, negations—belong to the panting insatiability of “Gombrowicz” himself, as he negotiates sexual devastation, poisonous

and ecstatic social maneuvering, moral collapse, political ambivalence, and a country manor murder. The manic oscillations of this voice escort us into the wonderful, horrible core of the novel, a whirl of masks, duplicity, flesh and fragmentation.

It is a universe where an atheist must pray with true sincerity, deceiving even himself, to cover up the “immensity of his non-prayer,” where a girl’s hand is “naked with the nakedness not of a hand but of a knee emerging from under a dress,” and where all human endeavor might just be a “monkey making faces in a vacuum.”

Outlandish metaphors, syntactical bolo punches, arias of exquisite paranoia, these are not adornments in Gombrowicz, they are the essence of his style. His word play is deep play. “In the end a battle arises between you and your work,” he wrote in his public diaries, “the same as that between a driver and the horses which are carrying him off. I cannot control the horses, but I must take care not to overturn the wagon on any of the sharp curves of the course.”

Helping to keep the wagon upright here is Danuta Borchardt’s brilliant new translation, the first in English from the original Polish. Borchardt’s

Pornografia

honors both the wildness and the precision of Gombrowicz. She preserves his sudden and propulsive tense shifts and reveals a treasure of new cadences and swerves. Consider an older translation’s description of the pious Amelia’s sudden undoing in conversation with the novel’s chief instigator, Fryderyk: “She was dumfounded (sic) and disarmed …” Borchardt’s version is not only more vivid, but pivots

on the weirdly compelling repetition of a word: “Knocked out of the game … she was like someone whose weapon had been knocked from her hand.” Better still is Borchardt’s Gombrowicz’s take on nightfall. The older translation details “… the sudden expansion of the holes and corners that fills the thick flux of night.” Fine, if a little vague, but it is no match for “… the intensification of nooks and crannies that the night’s sauce was filling.” The “night’s sauce” is almost more than we deserve.

But it is never a matter of what we deserve. I certainly didn’t deserve the gift of Gombrowicz when a good friend gave me

Ferdydurke

many years ago. I was just a young jerk who thought he had a fix on the frontiers of literature. But that book and others revealed the raucous speed and sublime vaudeville the right kind of runaway wagon could deliver. All who enter may revel in the many-layered excitements of

Pornografia,

though the reader is advised to refrain from slapping easy rejoinders to the existential difficulties the novel raises. “The primary task of creative literature is to rejuvenate our problems,” said Gombrowicz in

A Kind of Testament,

a series of interviews with Dominique de Roux. And Gombrowicz did exactly that, through philosophy, satire, critique, all of it powered by a subtle and vicious comic prose that continues to offer dazzling views of our individual and collective derangements.

“I am a humorist, a joker, an acrobat, a provocateur,” he once said. “My works turn double somersaults to please. I am a circus, lyricism, poetry, horror, riots, games—what more do you want?”

Let me know if you think of anything.

A translator does not work in a vacuum. I therefore want to share with the reader the names of those who with their works or in personal communications have informed my translations. You will find the list at the back of the book.

This is the third of Gombrowicz’s novels, and most likely the last, that I have translated. Since there were omissions on my part in giving credit to those who are due, I would like to make amends. Beginning with John Felstiner and our translation group at Skidmore College in 1998, I want to go on expressing thanks to my friends Nona Porter and Alan and Barbara Braver whom I have buttonholed on many occasions. Professor Stanislaw Bara

ń

czak was the one who gave me the first impetus and encouragement to translate the first book—

Ferdydurke.

I had given Thom Lane previous credit, but this bears repeating. I want to thank him for his indefatigable assistance, as the native speaker of American English, in translating the three novels. His wide reading of literature and his keen intuition, since he knows no Polish, helped me

to accurately express Gombrowicz’s ideas. I am also most grateful to Alex Littlefield, my book editor, for his sensitivity in approaching this difficult and idiosyncratic text. Last but not least, my thanks go to Eric Price, the C.O.O. and Associate Publisher of Grove/Atlantic, Inc., for accepting my translation for publication.

The first thing that strikes one about Witold Gombrowicz’s book is its title, so I will open with the author’s thoughts on its translation. In his conversation with Dominique de Roux in

A Kind of Testament,

Gombrowicz tells de Roux how he began writing the novel in Argentina: “… The year was 1955 … As usual, I began scribbling something on paper, with uncertainty, in ignorance, in terrible poverty that had visited all my beginnings. It slowly became rich, intense, and thus a new form emerged, a new work, a novel which I called

Pornografia.

At that time it wasn’t such a bad title, today, in view of the excess of pornography, it sounds banal, and in a few languages it was changed to

Seduction.

” Perhaps when he chose to call his new work “Pornography,” the word suggested something rare, hidden, a dark secret. I have left the title in Polish to convey shades of meaning the English may not have.

Since

Pornografia

has already been translated into English, the question arises why do it again. The simple answer is that

the previous translation was from a French translation and not directly from the original Polish text. There are bound to be mistakes in any translation, but Gombrowicz’s idiosyncratic and innovative use of language adds to the problem. Since the previous English translation was from an earlier translation into French, misunderstandings and errors were bound to multiply.