Back of Beyond (50 page)

A hand on my shoulder. Not a friendly hand. Two female Schwarzeneggers block the aisle and stare at me with outraged grimaces. No “be-friendly-to-foreigners” attitude here. They make it very clear I’m in alien territory. One has her notebook out. I’m going to get ticketed for trespassing? The larger one of the two points back the way I came. Everyone in the carriage is laughing. I start laughing too. Glasses of maotai are raised in salute. I lift my sticky bun in farewell and obediently follow the guards back to the quiet cocoon of my soft-sleeper. They berate Yves and Barney, who look very serious and guilty, like naughty schoolkids. I can see my guides are losing face rapidly. I turn on all the charm I can muster, hold the hands of the two guards, look downcast, and bow a little and mumble inanities softly. That seems to calm them. I look for some token of my atonement, and all I can find are two ballpoints stamped with a U.S. gas company logo. I mumble some more inanities, give them the pens, and they seem confused about what to do next. A final half-hearted reprimand. I smile a last apology. They both smile back and close the door firmly behind them. Duffy opens one eye and laughs. “You got further than most.” Barney and Yves ask me not to do it again and resume their tea-sipping stupor.

The last gashes of sunset now. We pass small dusty villages of tightly packed houses, each with a little red sign above the door. “That one says ‘Have a happy marriage,’” Yves tells me. “That one ‘We love our new son.’” Two cyclists pedaling home pass an old man leading two oxen with enormous horns. Tiny tractors like overgrown lawn mowers return from the long lines of paddies, leaving trails of scarlet dust. A huge moon rises over low purple hills….

Sleep comes easily on our hammocky beds. Through the night I half remember stops and starts and occasional clusters of dusty people waiting under dim streetlights near lonely platforms. Beyond are more long plains bathed in moonlight.

Six

A.M.

and the loudspeakers begin. Marshal music followed by interminable announcements in Chinese over crackling loudspeakers. Maotai hangover time. Bathrooms (a euphemism for one john and one hand basin) have long waiting lines. Everyone’s bleary-eyed and silent. We decide to have an early breakfast and then wonder why: It’s only rice gruel in a chickeny stock with flecks of green, and sticky dough buns. Yves slurps away at his noodles. Barney sips tea. Duffy is still sleeping.

Outside, total transformation. No more rice paddies and villages and lines of poplars now. We are deep into desert. Vast vistas of a gravelly wilderness edged by golden dunes and hints of blue mountain ranges. Occasional glimpses of sheep and goats on barren hillsides cut by deep gullies. After the chaos and congestion of the city and the verdant intensity of the plains, this land feels emptier than anything I have ever seen before. An enormous sandy sun shines across all this nothingness—fringes of the great Mongolian grasslands.

Duffy wakes up, takes one look outside, grunts a long, “Oh gawd no,” and covers his head with a gray-green Chinese railways regulation government blanket.

A young man steps in our door. “Please, I am student in Shanghai and would much like to practice my…” The green-uniform guards pounce like panthers, and that’s the last I see of him.

An older man passes. We had spoken in slow English the previous evening. He is a teacher in Beijing and is coming home to Baotou for a few days’ vacation with his family. He pauses at the door. “I wish I could invite you to the house of my father, but there is not time to get permission.”

“You need permission?” I asked incredulously.

“Oh yes, of course. And usually they say no. Especially away from the city…”

“What happens if I just turn up?”

He looked startled. “Oh no! There are too many people who watch…they tell…very difficult…”

We both smile sadly and shake hands.

Another station stop. Barney and Yves have been waiting for it. “Come, come,” they insist, so we tumble out onto the chilly platform and rush to a tiny blue shack to buy hot, greasy pancakes filled with chopped vegetables and other intriguing bits and pieces. Yves brings out his special soy mixture and sprinkles it lavishly over our steaming slabs of dough. Further down vendors are selling oranges, hard-boiled eggs, cold chicken with rice, packages of dried white noodles (Yves, of course, buys an armload), and tiny jars of spiced pickles. The whistle blows, everyone crams back onto the train, guards whisk away the vendors like wastepaper, and we move on again into the bright new morning.

Our destination must be approaching. The loudspeaker is getting louder, women are coming through, sweeping floors (ours is an utter wasteland of discards but they don’t seem to mind), removing Thermos flasks and spitoons, ordering the beds closed (Duffy sleeps on regardless).

Images are piling up again as we near the city: groves of delicate bamboo sway in the breeze; a soaring sandstorm way off to the east; flocks of dusty goats squeezing down the narrow lanes of a village of mud houses; a mule drawing a cart piled high with feathery desert scrub for kindling. Different kinds of faces here. More weathered, stronger—flickers of Ghenghis Khan and his conquering army of Mongol hordes.

Finally we arrive in Baotou and it’s chaos once again. Everyone rushing to get out of the station before the crush. Duffy awakes and advises a relaxed approach. He drinks some of Barney’s tea in a leisurely display of gentlemanly ease. The guards can’t understand why we won’t join the throng….

Out into the main square. Crowds of people once again. High drab buildings decorated with red banners (but no posters of Mao). Street stores galore selling pickles, buns, cigarettes, maotai, and cookies. Street snack bars with white-hatted waiters serving rice gruel and dim sum breakfasts. More loudspeakers and marching music for a hundred railroad employees who do ritual exercises in front of the railroad offices. Huge volumes of steam from the locomotive that has pulled us from Beijing (they still build these great cast-iron creatures to run China’s forty thousand miles of railroad); sidewalk displays of used Chinese and Western magazines for sale; big billboards advocating one-child-only families (big fines for additional children plus official reprimands from local party comrades), also billboards of TVs, bikes, watches, radios (materialism is rife here and new bonusincentive schemes for workers encourage “patriotic” consumerism). “Not too much, though, not too fast,” one student told me in Beijing. “You must be careful. Official policy changes fast. You buy fancy things one week. Next week confiscated! People still remember the Red Guards.” (All this was months before the Tiananmen Square debacle.)

A sudden glimpse of cracks in the social façade. People seem so placid and self-contained in the endless crowds of bicyclists pedaling to work. Then, one cyclist falters and brings down another behind and two more on either side. The flow is broken. Pent-up fury erupts instantly. Inscrutable faces turn furious and purple with rage. A hundred people suddenly shouting and cursing and blaming one another in utter confusion. A brief flurry of fists. Police and rail guards run and begin loud reprimands. No real damage to the bikes but a glimpse of hoarded anger. Frightening. Normalcy returns eventually, and the sea of cyclists waves on. Everyone seems calm again. Order has been restored.

Without strict control and imposed discipline one wonders what China might be—a nation of one billion creative dynamic live-wire capitalists or a place of utter social chaos? Maybe a bit of both. More recent events have proved the government’s reluctance to take chances. “Democratic” freedom is anathema to totalitarian regimes.

Duffy has the last word as usual. “In China, nothing is what it seems. Especially nowadays.” He smiles through black morning stubble and maotai eyes. Barney and Yves nod in agreement and wonder where to find more hot water for tea and noodles.

I can hardly wait for the next stage of our journey together, deep into Inner Mongolia.

CHINA—INNER MONGOLIA

Silence in silver limbo.

I lay in the lee of a sandy hill. Spears of brittle grass rose from the still-warm earth and glowed in brilliant moonlight. I could see for miles across gently rolling plains—across the vast silvered silences below a canopy of black velvet, pinpricked by a billion stars.

A soft crunch and I turned. The man, silhouetted on the hillside, paused, spotted my movement and came down slowly. It was the commune secretary, an elderly individual of grace and almost constant humor, who had never stopped smiling since we arrived at this lonely herdsman’s house in the heart of China’s Inner Mongolian grasslands. He eased himself into the sand, and we sat together without speaking for a long time, looking out into the glowing night.

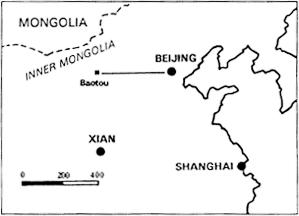

Was I really here? The place—the whole experience—had an ethereal quality to it—the fulfillment of a fantasy. Somehow I had arrived in the heart of this mysterious, almost mythical, land that forms part of China’s northern boundary for over eight hundred miles, a region the size of Texas (three times the size if you include Outer Mongolia to the north, now a separate nation within the USSR sphere of influence). From Hohhot, capital of Inner Mongolia, you can extend lines on a map to the north and west across deserts, mountain ranges, grassland plains, and steppes and never touch a major road, a city, or even a village for over two thousand miles!

Somehow, after a desert journey I’d gladly forget, I arrived at this lonely place in the middle of nowhere to spend time with the Mongolian descendents of the infamous Genghis Khan, one of those characters of history whose predeliction for cruel conquest during the fourteenth century filled my schoolboy lessons with bloodcurdling images. Somehow I’d been allowed in by the authorities after days of negotiation—the first Westerner to visit this “closed area” since the revolution of 1949. I’d come to see how people lived in these vast spaces. I’d come to meet the herdsmen, who endure torrid summers and the shrieking Siberian winds of winter when temperatures often sink to—40°F or below, all for the sake of their precious (and very tough) Kashmir goats, whose silky underlying fleece produces the world-famous cashmere wool.

The commune secretary was still smiling as we sat looking across the endless horizons skimmed by moonglow.

At the top of the hill we returned to the world again. In a dip to our right a couple hundred white sheep and goats lay huddled together around a solitary tree (trees are as rare as people in this vast nowhereness). Ahead, the small three-room farmhouse was a flurry of noise, light, and activity. Figures scurried around inside the high-walled courtyard at the front of the house, hefting huge slabs of just-slaughtered sheep into the kitchen. Steam poured from two giant woks perched on furiously flaming coal stoves; the shy girl with brilliant red cheeks and broad Mongolian face was obviously in charge and directed her helpers with Bernsteinlike bravado. (She only went shy outside the kitchen!) And from the living room came the now-familiar toasts of “ganbei!” as yet one more round of fiery maotai liquor—scorched a score of throats once again. And the scratching and yowling of strange stringed instruments—the morin khour, hugin, and erhu—and the wail of the bamboo flute accompanied yet another plaintive “long song,” sending it soaring into the night through the bright candlelit windows.

On the raised platform, or

kang

, which stretched fifteen feet from wall to wall at the far end of the room, sat the motley members of our expedition—Ed Duffy, China trader, self-proclaimed “King of Cashmere” and raconteur extraordinaire, our interpreters Yves and Barney (very Anglicized versions of their unpronounceable Chinese names), Tony from the Dongsheng cashmere factory, and our silent driver—all humming a discordant harmony as Etu, the singer, pushed her sad notes higher and higher and the two-stringed hugin fiddle screeched its closing chords.

“Duffy-sing, Dawi-sing! Sing, sing!”

So once more Duffy and I launched into ribald, half-remembered choruses of old sixties party favorites plus the inevitable “Skip to m’Lou,” which they loved best of all but could never quite make the words sound right (“Sip-u-mee-oo” was about as close as they got. Visiting anthropologists will one day ponder this odd fragment of dialect.) And they clapped and we clapped and the songs raced faster and faster and the candles trembled as twenty strident voices blasted out the inane lyrics into this night-to-end-all-nights in the middle of nothingness—lost in the great grasslands and loving every second of it.

Getting here in search of the Kashmir goat herdsmen had been a long and arduous process. The journey was planned with the precision of a Napoleonic campaign but invariably suffered from those interminable delays and frustrations that seem an integral part of travel in China, if you are determined, as I was, to resist standard tourist itineraries.

“Everything’s just fine,” we were told as we left the

China Flyer

train after the seventeen-hour night ride in “soft-sleeper” to Baotou on the fringe of the grasslands. “You’re off tomorrow,” they said as we drove another one hundred miles across a Saharan wilderness of magnificent golden dunes to Dongsheng—and the first of our logistical roadblocks.

Someone in authority had realized that my route entered “closed areas” and suggested we make do with a visit to the special tourist “nomad camps” of traditional felt and canvas yurts (Disneyesque collections of herders’ tents set on concrete plinths with all modern facilities!), a couple of camels, some wrestling, and maybe horse-racing if the weather’s good. “Very good photos—very much color,” we were told.

“Sorry,” I insisted. “We’ve come to see the

real

Inner Mongolia. We want to stay with a real herdsman—yurts or no yurts!” It didn’t seem a lot to ask, but to the Chinese authorities it was an outrageous proposition.

“These areas are closed. There has been a mistake. Have some tea.”

In this country where “face” is a key factor of communication, no one likes to say “no” outright!

And so the meetings began, sixteen in all, and we became increasingly depressed. Finally, on the third day, as we waited for the ultimate “no” to be pronounced, in walked the local chief of security police and declared that we may go where we wished and that special passes would be issued immediately.

“You are very lucky,” he told us as we toasted one another’s endurance. “You are going somewhere that has never been opened to Westeners before. You will see many things. You will remember this journey.”

How right he was.

Out, out, and even further out. Across eroded hills, over vast areas of dunes, salt flats, and high steppes where wild horses roamed the horizons, silhouetted against burning skies. Out where the road became a track, then a vague marking in the soft earth, and then nothing but an improvised line of sight across dry hardscrabble grasslands. Out across more than three hundred backside-flattening miles of empty country into the unknown, to find the herdsmen and a place to rest for a while. We were a happy and expectant bunch of explorers and quite unprepared for our next challenge.

It began innocently enough—brief buffetings of breezes from the north and the prattle of blown sand on the side of the Jeep. Then—almost imperceptibly—the sun began to take on halos, a series of strange golden rings in a gradually yellowing sky. Dust devils whirled up in the distance, first one, then four simultaneously, then a whole stretch of grasslands spinning skyward in a swirling column.

We all became quiet. The driver sat up straight and tightened his grip on the wheel. Then the sun disappeared. Just like that, it vanished in a strange beige mist and sand began blowing in through the open windows. “Uh-oh!” groaned Tony. “A blooty sandstorm.” (Tony always had problems with his

ds

). In less than a minute visibility was down to yards, and a gale came howling straight across our path, blowing the sand horizontally. We closed all the windows. The heat became unbearable and fine dust still billowed through. Sweat streamed down our faces in brown rivulets. The track—hardly more than a path—kept disappearing, and telltale tiremarks ahead were quickly obliterated. At one point we almost ran straight into a dune, until we realized that the dune itself was actually moving across the track in front of us, driven on by the furious wind. The driver’s face was as set as stone. Somehow we kept on moving. Six times we hit soft sand and labored out with four-wheel drive. No one talked—we all watched for signs of the route and willed on our silent driver.

“We must not stop,” Tony broke the silence. “Neber” (Tony also had problems with his

vs

). But fate had other plans.

We stopped as abruptly as hitting a barn door. We had lost the track and slid into talcuum-soft sand. This time the super-drive failed, and we sank deeper.

“Out—push” said Tony, and we knew it was the only way.

The next few minutes are as imprinted on my mind as the “sand burns” were on my body. We heaved and gasped and heaved again in that mad maelstrom. The wind was blastfurnace hot and the sharp sand filled every pore. We were five deaf, blind, suffocating creatures, hardly human, struggling to push the heavy Jeep out before the newly drifting sand sealed her even deeper. We were motivated by an increasingly real fear of being stuck and cut off by dunes without supplies in this howling wilderness.

Somehow we did it. Somehow we found the track and somehow we got out of that place. And just before we left I looked behind and saw, like ghostly shadow puppets, the faint silhouettes of two camels moving together through the fury…I called to the others and we all turned. But they were gone.

And the party rolled on at the herdsman’s house in the middle of nowhere. After the sandstorm, fate was kinder to us, and by evening we had found the perfect place to stay—this small brick house in a hollow with a family whose welcomes and kindnesses never ceased.

We had become celebrated guests of honor, a sheep had been killed for us in the courtyard (it is customary to watch the ritual but I invented some lame excuse and didn’t), and, as we sprawled like Arabian potentates on the cushions and rugs spread across the kang, we could smell the meat—the whole animal—cooking in the adjoining kitchen.

And the dancing and the songs continued with no letup in pace or enthusiasm. I remember one Mongolian long song with the most beautiful words:

I am a small flower hidden in the grass

The spring winds let me breathe and grow high

I live in the mountains and in the grassland

The grassland is my mother

I love Mongolia—I am Mongolia.

“In Mongolia,” the pretty red-cheeked girl from the kitchen explained, “a person who cannot play the flute or the morin khour or sing the songs of this land is not alive—is not human—is not Mongolian! And,” she added with a serious frown, “I am Mongolian, not Chinese. We are not Chinese!” She spat out the last word.

Then she whispered to her friend, who was also acting as our interpreter. “She wants to know if she can touch your beard. She has never seen a West-man before. She has never seen a red beard!”

So the apple-cheeked girl stroked my beard with her plump fingers, blushed even more brightly, and scurried back into the kitchen to supervise the cooking. Her friend laughed, as did the others around the table. Then she leaned over and whispered: “They are very happy you are all here…they are very glad you come.”

The night was full of moments like this. One song was so sad it left us all teary-eyed—even the singer; another was so loud and clap-happy that our palms blistered; a third, a rowdily erotic drinking song, transformed our placid driver into a raging romeo with a Mario Lanza voice and a lust for the pretty female duetist as big as his larynx.

Our herdsman-host at one point invited me to look at the old photographs of his family and relatives hanging in large frames on the wall next to a brightly painted red-and-green chest of drawers, one of the few pieces of furniture in the house. He led me outside into the moonlight to stand by the shrine to his ancestors, decorated with banners and ribbons and the remains of offerings. It stood like an altar just beyond the courtyard door, guarded by two silvered replicas of Genghis Khan’s trident spear—the prime symbol of Mongolian identity and pride.

Then a great shout went up. It was 2:30

A.M.

and the tiny house roared once again into frantic activity; people ran around with fresh bottles of maotai, gleaming plates, huge Mongolian meat knives, and baskets of fat white bread buns. “Sit-sit-sit!” we were told. “It’s coming!”

And so—it came!

A mountain of meat emerged on a platter the size of a car hood; thigh-size chunks of juicy mutton piled up pyramid-fashion and covered with the sheep’s fatty back (rear end pointing toward me as guest of honor!), topped by the whole head, eyeballs, horns—the lot—smiling through billows of steam and the whole vast display dripping deliciously….

I cut the first slice with a ritual knife, and then it was a free-for-all as twenty ravenous revelers tore the exquisitely tender “finger mutton” from the bone and scooped moist meat into mouths sore with songs and scorched from over seven hours of toastings.