Back of Beyond (51 page)

And what a feast it was, flowing on and on into early dawn with that special camaraderie that comes from unexpected mutual enjoyment and excitement. At around 5:00

A.M.

bodies collapsed one by one onto the kang; herdsmen, their wives, children, commune leaders, all of us, shoeless and serene, for two hours of deep sleep before breakfast.

Blurry-eyed, we awoke and washed in an enamel bowl in the courtyard. The sun was already warm and over the wall, I could see the goats beginning their never-ending search for grass across the hazy hills.

Bowls of mare-milk tea came to the table on the kang along with dishes of hard yellow millet, sweet yak butter (

souyou

), a golden pile of fried dough, and tooth-cracking cookies baked from yogurt and flour. Amid elaborate mixings of tea, millet, and souyou (stirred with the little finger), we slurped in unison, as was obviously the custom. Someone sprinkled the earthen floor of the room with water to keep the dust down and removed a couple of errant chickens wandering in from the courtyard. The women were busy as usual, cleaning, feeding a sick foal, checking the herd, milking the goats and horses (fermented mare’s milk is used to make the potent

airag

drink of the herdsmen), and removing traces of the previous night’s revelries. The men sat quietly, slurping endless bowls of tea, smoking ferocious little Mongolian cigarettes, and talking quietly to us about the old days in the grasslands.

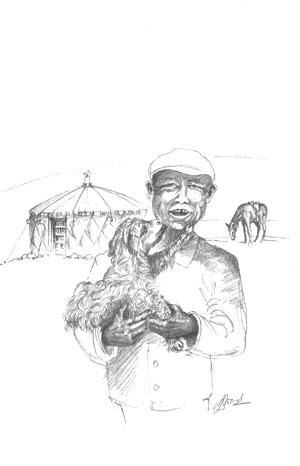

We were curious about changes in the nomadic traditions of the herdsmen. Once the great grasslands were full of wandering groups of families with their herds of sheep and goats, living in ingenious round yurts made of layers of felt, canvas, and hides stretched over wood-lattice frames. They would select temporary camps, as many as ten different sites a year across the immense plains and ranges, moving their flocks, horses, and camels through sunny summer days and furious winter blizzards. The famous Kashmir goats were renowned for their endurance and the silky quality of their underlying fleece, which retained warmth in conditions that would freeze a man to the marrow in minutes.

“Oh, we still have our yurts,” our host told us. “Smaller ones though now. Normally we don’t need them, the grasslands are better irrigated and most families build houses nowadays and stay in one place. Sometimes though, if the rain is late, like this year, we send the younger men off with the herd to new pastures, and they live in the small tents. But it’s mostly communes now—there are around eight hundred families in our commune.”

We looked out over the vast empty spaces beyond the courtyard.

“Ah!” He laughed. “You won’t see many of them! We live a long way apart, we’re quite independent, but for certain things we all come together. Particularly for weddings and the big festivals—we come together for the wrestling and the racing—and the maotai. There are over ten million people in Inner Mongolia, but you’ll hardly see any. Strangers don’t realize—they can’t imagine—just how far these grasslands go. For hundreds of miles”—he stretched his arms as wide as he could and smiled gently to himself—“hundreds of miles…”

His smile was a smile we came to know well with these people. We called it the “Genghis Khan grin”—a proud knowingness of the immensity of their land, a smell of freedom in the wild unchecked winds, a sense of “possessing the whole earth,” which must have given the great conqueror and his Mongol hordes the grand visions of world domination that they essentially achieved during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

“We’re just herdsmen now,” said our host, but there was that flash in his eye that still sends shivers down the spines of the Han, China’s primary racial group, who have been actively settling in these wild regions for decades to the point where they now form over eighty percent of the population.

I wondered about the two-humped Bactrian camels, once the main mode of transport in the grasslands.

“Many things are changing,” they told us. “We still have our camels, but we let them wander for most of the year. We don’t need them now to carry the fleece to the cities. They usually come home to birth and then leave again. We concentrate on our goats and sheep—these are our life.”

Over the slow, easy days, we watched and became part of the steady rhythm of their lives. I sat cross-legged on the ground while the goats were combed for their precious white cashmere fleece, hardly more than four ounces per animal (“…takes at least twenty goats to make a good sweater”). I wandered with the younger herdsmen over the high windy hills and watched them use their pebble-throwing

yang-cha

sticks with unbelievable accuracy to keep their animals in check. I ate the hard

arul

cheese and drank airag for lunch in the bright midday sun.

And in the silences my mind would fall silent and become as vast as the spaces around me. It seemed that everything I saw was actually within me, within an all-enveloping mind—an eagle, alone and soaring on spiraling air, a flash of light on quartz crystals, a wisp of wind rattling the grasses, the crack of rocks splitting in the dry, hard heat. I had never sensed the power of silence so intensely: each object seemed wholly distinct and full of individual energy and yet totally a part of everything around me. And even my own body and spirit—for fleeting but seemingly infinite moments—became a part of the land in the vibrant wholeness of this magical place.

Eventually, we left, a lot more quietly and stilled in spirit than when we arrived. The herdsmen had allowed us to become part of their world for a brief period and to sense the slow, steady rhythms; the strong underpinnings of their lives. The ribbons on the ancestors’ altar table waved in a warm breeze as we said our farewells, and the trident of Genghis Khan gleamed as bright as ever in the morning sun.

We headed off across the sandy hills; my mind was too full of feelings to talk, too full of excitement at what we had found, too full of anticipation for what was to come next….

Time to fly.

The ground had held me too long.

I needed another landscape—a free-form topography of blue and white. I needed to float among the hammerheads, to ride the updrafts into a world beyond the grist and grind of the human merry-go-round—to leave the earth for a while and touch the wild places

inside

once again.

A friend had a plane, a tiny Piper Cherokee, forever tied down by a runway, too far out of town for casual jaunts. He dreamed of great journeys—an Atlantic crossing via Newfoundland and the Azores; a Pacific odyssey full of touchdowns on Robinson Crusoe Islands, a world circumnavigation with stops in all the forgotten places. But the plane just sat there, full of tantalizing possibilities, draped in dreams.

“America from Five Hundred Feet.” What a splendid book idea excuse for this serendipitous photographic adventure. To bid farewell to the concrete calamities and the tawdry esthetics of the earthbound. To lift up, out, and off, leaping into infinities.

So we did.

I was proud of him. Beneath the careful man, clogged by schedules and mind-bound by meetings, I found the spirit of the boy, brimming with fantasies, clutching the cirrus tails, reaching out to touch new possibilities.

A small plane is pure magic. For what seems like forever, you’re ticking off checklists, testing tires, tediously playing with dials and switches, deafened by the prattle and boom of the little engine, talking gibberish to robotlike voices in the tower, noting details about wind speed and air traffic and vectors and quirks of the ever-fickle weather. And then it’s suddenly different. The runway skims by, the engine screaming in anticipation, the nose lifts, the seat springs groan and creak as your body weight doubles in that first thrust of flight, and—you’re off. The ground drops away, becoming a rinky-dink, toy-town picture book of dollhouses and Matchbox cars and spongy trees and tiny white-spired churches.

The world is all yours. You can go anywhere, do anything. Turn left, turn right, fly in circles, climb, dive, do a somersault, loop a loop if you must, play peek-a-boo with clouds, chase a rainbow, tease a thunderhead, skim the spuming surf, kiss a mountaintop, make the long grasses wave like silky hair, roll your wings at a farmer in his field, bombard the cumulus galleons with their wind-ripped sails. Your spirit soars with the Cherokee; you feel light as duck down, free as a feather. And you remember, you know again, just how precious and perfect life and being alive can be. The high of the whole. The best high of all. Because it’s true.

Look up and it’s a pure Mediterrenean-blue dome, arching over to a golden haze. Look down and the patterns intermingle: the patchwork panels of fields, a random quilt of greens and golds and ochres; the pocket-comb geometrics and curlicues of ploughed furrows; the silver-flashed streams; the Baroque tangles of woods and copses on humping hills; the sprinkle of villages along a tattered coastline ribboned with white surf. Gone are the gas stations and the hype lines of neon-decked motels and junk-food stands and auto showrooms and traffic lights and do-this do-that signs and billboards and all the gaudy excess of street-bound life.

This was a new world up here, fresh, bright, traffic free—and all mine! I wanted to shout down to farmers and tell them how beautiful their fields looked—bold abstract masterpieces of color and form that could grace the walls of any gallery. I saw lovely things: a single fishing boat with the shadow of a galleon, apexed in a flat pyramid of cut ocean; the fluid lines of submerged reefs, receding in filigreed layers from turquoise to the deepest of royal blues; moonscapes of gravel pits and quarries concealing pools of clear green water; the silty delicacy of estuaries edged by curled traceries of emerald marshes; Frankenthaler earth patterns of water absorption in fields of new wheat. It was an esthetic unfamiliar to me. A world of fresh beauty; juxtapositions of form, color, and texture I’d never imagined before.

Evening eased in slowly and seemed to last forever. As the sun slid down into its scarlet haze, we rose up to watch the shadows scamper across the rolling land. A modest line of trees following a winding country road cast quarter-mile-long shadows, purpling the furrows. Little hillocks produced mountain-sized echoes of themselves across the fields. Even a tiny white farm cluster of barns and outbuildings became a Versailles shadow, suggesting towers, turrets, and elegant cornices. Cows were giraffes, a tiny red truck became a triple-decker bus, a man heading for home across a bronze field was a stick-legged giant.

And when the night came, it came with grace in a slow canopy of velvety purple, sprinkled with stars. The west gave up its glow with reluctance and the night allowed a dignified retreat. An equitable ritual, well rehearsed over the eons. And we watched the gentleness of it all, floating easily in the evening air, not wanting to leave, reluctant to face the disordered scramble of earthly matters. So we flew on, abandoning ideas for a touch-down somewhere in the flatlands below us. Food and flight plans, taxis, motels, and beds could all wait. The night invited us to stay and we accepted, watching it flow in, filling the lower places, rising up the flanks of the ranges, leaving little islets of light on the high tops for a while until they too were submerged in the purple tide as we floated on into the mysteries of the dark.

The tale of our odyssey across America from five hundred feet must be left to another time. It was a fascinating journey, a photographic record of esthetic experiences rarely matched by earthbound adventures. At the outset I had merely wanted to fly for a few hours, a few days, to get my world-wanderings in a fresh context and think of future directions for my life and travels. I had never expected to discover such new joys in the experience of flying itself—flying as an end rather than a means. My notebooks (rather shaggy things now, full of untidy scribblings, stained by spilled coffee and oil from a leaky engine pump) still tingle with a novice’s sparkle-eyed euphoria:

—slow curling rivers—gentle essays in time—histories written clear on the earth: oxbows, old courses with the sinewy shadows of snakes; ancient lakes, now limpid marshlands with flurries of egrets rising to meet us

—spuming deltas with silt patterns like duck feathers; the thwack of midday sun on still water, gleaming like a new Porsche; forest-shaded curves where the bass lie cozy in the slow cool depths

—a range of snow-crusted peaks, seemingly another blending of cloud banks, then slowly taking on a sharper form of arêtes, ice ridges, and glacier-gouged ravines

—rising through gauzy morning mists, slipping off “the surly bonds of Earth,” up into the purest blue that goes on forever.

—a swirl of silver-gold dunes, soft sensual curlings and rounded shadows—the pretty petticoats of shattered peaks

—the bare beige endlessness of sagebrush country, but also the strict patterning of the bushes, each occupying a precise and evenly spaced territory, geometrics of logic rarely discernable on the ground

—faint radial scratchlines on a dry scorched land coalescing at a muddy brown waterhole in the middle of nowhere

—into canyons of cumulus, playing tag with the giant thunder-heads, skimming the black tentacles of a storm column, feeling the life of this fleeting creature illuminated from within by its own lightning

—seeing our cruciform shadow, projected giant-size by the sun on the clouds, haloed in gold; suddenly from an insignificant speck we become manifest

—the unearthly solitude of flying above the clouds; it all belongs to me, utter limbo-land; the ultimate “I am”

—a sprinkling of ponds and little lakes, hardly visible at first across the dun Maine tundra, suddenly sparkling like scattered pearls, then neutered again as we fly on

—the gleam-sheened waterworld of the Atchafalaya bayous where the hard earth dissolves into droopy cypress swamps and blue-green blankets of reeds and fields of floating hyacinths

—jousting with the Arizona buttes, red-ochre remnants of ancient plateaus, pointing skinny fingers at the sky, chiseled reminders of time passing, skimming them with our wingtips

—close enough to see the flash of a vulture’s eye—and then off again in wild trajectories, deeper into the wilderness, not wanting to leave this empty place; waiting to hear its secrets

—our shadow dancing over the swirl and switchbacking of the Utah wilderness; no roads, no tracks, no sign of human life for hours, a place left to play by itself, rejoicing in its sinewy contortions, raged up in tectonic fury, cracked open and flung apart by the elements, gashed and exposed—a warrior torso of a land, garlanded with ribbons of colored strata, crowned with shattered pinnacles and cooled by storms, roaring across its scoured belly and screaming through its broken teeth

—up here, floating, apart from it all, indivisible; a sense of greater perceptions—hierarchies of knowingness just beyond the next truth. Like the paradox of particle physics, never quite getting there, merely seeing deeper and deeper, space beyond space into the inner universe with its constellations of quarks (strange, charmed, and all those other multicolored entities), mesons, gluons, neutrinos, gravitons (and even antigravitons), matching the complexity and scale of the outer universe itself—an equilibrium of endlessness

—up here, floating, you see it all quite clearly. The clamor of experiences, the search for something forever out of reach, out of comprehension. Seeking the mind of God in the fragmentary illusions of everyday life, playing with

his

possibilities, cracking open the creaky walls of knowledge and flying out into pure beingness…

I wished it would all last forever. But it didn’t, and finally we were back to the swelling hills of home, bosky with copses and stringy streams and things with associations, leaving all the wild places behind for a while.

But happy with a thought.

That the wildest places of all are deep within and there’s no end to the exploration and enjoyment of their mysteries and magic

.

And that is sufficient.

For the moment.

And finally, something I wrote a day or so after coming back home to Anne, the two cats and the lake….

Here

Once again

Smelling the grass above our lake

(rippled now and then with turtle bobbings)

and the burps of bullfrogs

and the unraveling of silver clouds

and the low pale light across the hills

and the sun in the wings of dragonflies

and the shaggy shadows of evening woods

and the woolly-misted air

and the stalk-stiff herons, like meditating monks

and the bobbling butterflies

and the sound of beetles sucking sap in the fat leaves

and the wind, knobbly with raindrops

and all the warm familiarity of this piny place

glimmer-green and fusty with ancient wood rot

and Anne

boiling the kettle for a little tea-and-talk

between the books and books and books

and all the fresh expectations

of new perceptions

new journeys

new wild places

and another new today

tomorrow.