Backstage with Julia (18 page)

Read Backstage with Julia Online

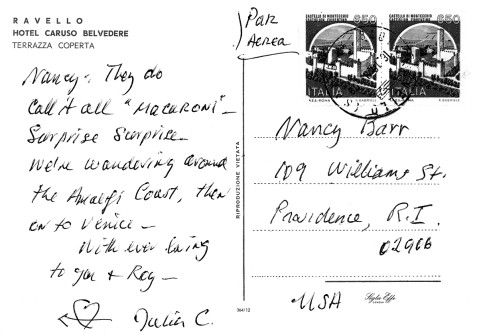

Authors: Nancy Verde Barr

At the time I sold that book,

We Called It Macaroni,

I was still working on a typewriterâan electric typewriter, but a typewriterâand Julia's immediate advice to me was "Get a computer." She was already using one.

So I invested in the computer; I bought a printer and reams of that old computer paper with yards of attached sheets folded on top of each other and tiny holes running down the sides to move it through the rollers. I loaded the paper in the printer, installed a word-processing program, and composed my first workâa letter to Julia. Her return letter was an enthusiastic response to my computer efforts.

"Dearest Nancy," she wrote in July 1985. "Delighted to have your letter on your WP, and aren't they wonderful! I'm getting really used to mine, and can do pretty much what I wantâbut do I know all that it can do? That will be an eternal question. Certainly, once you've gotten onto the processor (like the food processor), you'll never go back. However, I still have my electric typewriter, and use it for corrections on sticky tape."

Letters to Julia were easy; the book was hard. Not the recipesâI knew which ones I wanted to include, and I was as exacting as Julia was about testing and retesting. The problem was all that copy around the recipes. It did not exactly flow onto the computer screen, and I understood what Gene Fowler meant when he said, "Writing is easy. All you do is stare at a blank sheet of paper until drops of blood form on your forehead."

Judith was a no-nonsense, thorough, and exacting editor, and quite honestly, she scared me to death. She wanted cookbooks that told a story or at least said something, and that something had better not be drivel. Julia described Judith's editorial approach as "an iron fist in a kid glove," and indeed, Judith could not have been gentler as she encouraged me to write and praised my progress, but I still constantly feared that iron fist crushing my meager manuscript into hundreds of tiny shreds. (Years later, when I worked on my second book with Judith, I came to realize that the kid glove goes pretty deep. She no longer scared me; she simply overwhelmed me with her capabilities.)

When I was certain the amount of blood pouring from my head would cause my demise, it was Julia who mopped my brow and convinced me I wasn't going to die. It helped that she was also struggling with the book she was writing,

The Way to Cook

. She intended for it to be a comprehensive, instructional cookbook, but it was becoming massive and she knew she had to rope it back into a manageable shapeânot a simple task when you consider that this was the same woman who in her

Mastering the Art of French Cooking

books devoted eight pages to describing how to make an omelet and eighteen to French bread. "Oh, my book!" she wrote to me. "It is getting so largeâI have no idea how many pages but I've now done only two chapters, Poultry and Vegetables, and they seem immense, and it takes so long. How are you doing on yours?" And later in the letter, she admitted that she was "taking the day off as a reward for finishing my vegetable chapter. And I'm not going to take any work at all on this European tripâfor the first time ever!" I'll bet she didn't write that last part to Judith.

"Blue-pencil" is the term used for what an editor does in editing a manuscript. Originally, all editors wrote in blue so their notes would stand out against white paper and black writing. Judith doesn't blue-pencil, she green-pencils. And she writes in small, finely formed cursive. When she returned my manuscript with her first edits, I sat down and page by page read her clear notes. What was that in the margin outside that paragraph? The writing was much smaller than the rest, infinitesimal, and I had to get out a magnifying glass. It was one word,

nice,

with an exclamation point after it. I stopped going through page by page and began flipping the pages over rapidly to find more

nice

s. There were three. Three Pulitzer prizes on the first read alone.

Julia called me shortly after I received the edit and wanted to know how it went. I told her that Judith must have liked what I wrote about such-and such because she'd written "nice" next to it with an exclamation point.

The elevated level of excitement in her tone was unmistakable. "How many

nice

s did you get?" she asked.

"Three."

"Why, that's wonderful! I always look for them first. Never get too many, but I love it when I do." From that point on, Julia and I shared the number of

nice

s as soon as we received our edits from Judith.

So, though our problems were quite differentâJulia wondering what she could cut without jeopardizing her intent and I struggling with what to put inâwe formed a writers' bond that replayed some years later when she asked me to write two books with her. Julia was much too gracious a person to suggest even remotely that she had as much to do with my book as she did, but I know she felt a connection to it. When eventually she gave the majority of her cookbooks to the Schlesinger Library, she told me, "But I still have yours. Always will."

I cannot separate Julia from my professional career. I don't know if I ever would have written cookbooks or even magazine articles were it not for her. It is doubtful that I would have had the opportunity to work in television. She was all that a mentor should be, and when my personal life needed guidance, she provided that as well.

When I originally enrolled in Madeleine Kamman's Modern Gourmet culinary school, my intention was to follow my nonprofessional degree with a teacher's diploma. Two pregnancies interrupted that goal, and it was seven years before I applied to Madeleine for a student-teacher position. By that time, she had moved the school to Annecy, France, which meant I would have to fulfill my two-week apprenticeship there. It was a difficult decision because I had never left my family for such a long stretch. No less difficult was my awareness that I was entering enemy camp, so to speak.

Sometime long before I applied to the program, Julia explained to me why she didn't trust "that woman from Newton." When Madeleine first moved to Boston to teach cooking classes, Julia invited her to her home and introduced her to the local culinary community. Julia thought she had a great new ally in her goal of introducing good French food to Americans since she and Madeleine shared not only a passion for classic French cuisine but also an unwavering goal of teaching its principles and techniques. But then, for reasons only she could know, Madeleine wrote a critical letter to WGBH, Julia's public broadcasting station in Boston, stating not only that Julia was neither French nor a chef but that perhaps she had other issues that made her unfit for the show. Liz told me that it was a "vicious" letter. Then, during a newspaper interview, Madeleine told the press that she had taken classes with Julia's

Mastering the Art of French Cooking

co-authors Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle at Ecole des Trois Gourmandes, the cooking school the three had started in France, but had not learned a thing. She said she actually taught them a thing or two. Julia was at first stung and then angry. From that point on, even as I watched Madeleine try to assume a kinship over the years, Julia's comment was always, "Don't turn your back on her."

I'm not quite sure why Madeleine accepted me into the apprenticeship program, because from the very first class she was relentless in her quips about my work with Julia. "I suppose you learned that from

Julia

!" she'd say, and "Is that the way

Julia

does it?"âalways out loud in the middle of a class I was teaching. At one point, in an attempt to relax a young student who was near-spasmodically trying to bone squab, I put my hand on her shoulder and said, "Relax. Cooking is fun."

"Fun!"

Madeleine erupted from the other side of the kitchen. "You think this is fun? It's hard work and don't forget it." I tried to convince myself that it wasn't me, that Madeleine was just being her ornery self, but a fellow student teacher told me that she was appalled at the hostility vented my way. After less than a week, I found the constant animosity unbearable, and I thought longingly of Julia, who was at her home in Provence. Philip and I had spent four perfect days there with her and Paul before he returned home and I left for Annecy. I wished desperately I could return to the warm environment of her home.

So I called her. For years after, when Julia and I recounted the story of my experience, we always said I called "sobbing." We liked to tell it that way because Julia liked to parody me by making the most despondent sobbing sounds and it made the story all the more funny and dramatic. I don't recall if I actually sobbed when I called, but I have no problem remembering how wretched I felt. "This was a big mistake. I'm so miserable," I said. "I think I'm going to leave. I was thinking that I could come back to La Pitchoune until it's time for me to return home."

"Don't you dare!" she said firmly instead of cooing the you-come-right-back-here-dearie words I expected to hear. "You bull it through and don't let

that woman

know she's getting to you."

"Butâ"

"No buts. Just do it!" Had she no heart? I needed rescuing, but she would have none of it. She acknowledged that "that woman" was most likely taking it out on me because I was "consorting with the enemy," but she insisted I tough it out.

I stayed in Annecy and did not let on to Madeleine how miserable she was making me, and for no reason I can comprehend, by the time I left, her attitude had completely changed. She saw me off at the train station, where she presented me with a lovely blue and white faience serving plate as a gift. Go figure.

It wasn't until we were both back home that Julia, with unmistakable compassion, told me how distressed she had been I was having such a hard time. "I wanted to run right up there and snatch you out of her clutches." It was, of course, exactly what I'd wanted her to do at the time. Instead, she allowed me to have the satisfaction of having bulled it through a tough situation, which is what she would have done, and it felt damned good.

Chapter 6