Bastard Prince (37 page)

England could have been thrown into a civil war, with Richmond backed by the House of Howard and Edward's claim stoutly supported by the Seymour family. Henry's will had appointed sixteen co-executors to act equally on behalf on his son Edward. Yet within days of his death Edward Seymour had quickly secured his election as Lord Protector. Although it was agreed that he âshould not do any act but with the advice and consent of the rest of the executors' he soon assumed quasiroyal authority. If the mechanics of Tudor government meant it was âexpedient to have one as it were a mouth for the rest to whom all such [who] had to do with the whole body of the Council might resort' then surely Richmond would have been the obvious candidate.

If Richmond had lived it is possible to imagine the politics of Edward's reign taking a different course. Henry might have taken little persuasion to name his beloved eldest son as regent during Edward's minority despite his illegitimacy. He was, after all, his own flesh and blood and showed every promise of being more than capable of shouldering the responsibility. If the policy has unsettling shades of Richard III and his unfortunate nephews, it was perhaps preferable to the alternative of leaving Richmond isolated and possibly increasingly disaffected. Richmond had always been a loyal and faithful son. There is every reason to believe that he would also have been a charming elder brother, whose skill at hunting, hawking and the like was more than sufficient to engender a degree of hero-worship in his younger sibling.

Richmond was certainly intelligent enough to appreciate that there were more subtle ways to ensure a lifetime of influence and satisfaction than risking the usurption of the crown. Just as John Dudley, then Duke of Northumberland, chose to rule as President of the Council rather than Lord Protector, in the hope of extending his influence over Edward VI into adulthood, so Richmond could have presumed on their blood relationship and common ground to ensure that he remained at the centre of his brother's government. The only question is whether that would have been enough to satisfy the ambition of Henry VIII's eldest son, or the ambitions of the friends around him.

Richmond's survival would also have had further repercussions on the political landscape. In 1536 Richmond's funeral had provided an excuse to isolate Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, from the king's favour. In 1547 Norfolk's enemies had preyed on Henry's concerns about faction and division during a minority. Norfolk's position as one of the greatest nobles in the realm was used against him to suggest that he might seek to overturn Henry's wishes for a Regency Council. Chief among the charges against Surrey was âif the King should die my lord Prince being of tender age you or your father would have the rule and governance of him'. In the event, it was Seymour who gained the overall control that Henry was so anxious to guard against and why he was so keen to ensure Norfolk's removal.

The prospect of the king's own son as regent would have provided a far more difficult obstacle. Richmond's continued existence may have been sufficient to save the Earl of Surrey from the block and ensure Norfolk's continued presence on the Regency Council. In this scenario it is hard to see either of the pivotal figures of Edward's reign, Edward Seymour or John Dudley, being able to stand against a settlement laid down in Henry's will which named Richmond as regent and placed Norfolk at his side.

Although Edward's uncle might seem a natural choice as regent or Lord Protector, according to the terms of Henry's will Edward Seymour was ranked fifth in order of precedence. Seymour had relied heavily on the support and assistance of Sir William Paget

5

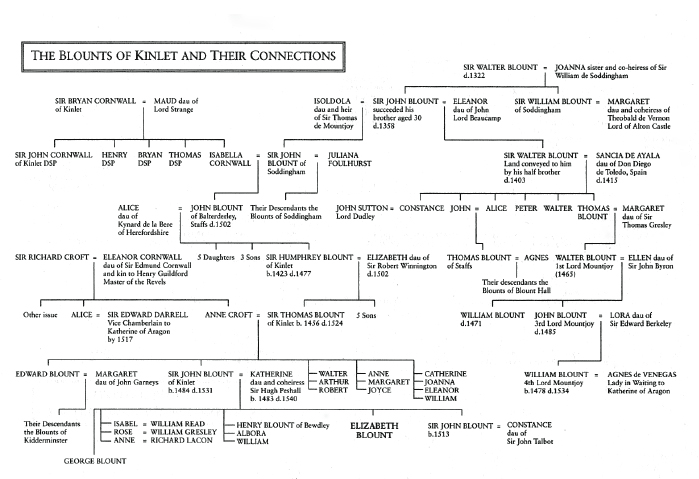

to achieve his goal. A selection of rather dubious grants (attributed to the wishes of the late king) bribed others to support his elevation as Lord Protector. Even then, it is interesting that he did not presume to declare himself regent. John Dudley, who took up the reins of power after Somerset's execution in 1552, enjoyed a good deal of support from Richmond's former step-father Edward, Lord Clinton. The two men were very close and Clinton married his stepdaughter, Elizabeth, Lady Tailbois, to Dudley's second son, Ambrose. Clinton enjoyed a larger share of gifts and grants during Dudley's tenure than any other councillor and repaid Dudley with his loyalty and military skill. If Richmond had lived, surely that support would have been placed behind his former stepson. After all, Clinton had his own family to consider and as Richmond's half-siblings his own daughters might expect to do well.

With Richmond as regent the history of England from 1553 would need to be entirely rewritten. Once Richmond and Norfolk realised that Edward was dying they would have been well placed to exploit the situation to their advantage. Everything suggests that Richmond and not Mary would have been next in line for the throne. Unlike Mary, Richmond seems to have been quite happy to toe the line of least resistance in religion and this is unlikely to have been an obstacle to his accession. There would have been no âdevice for the Succession' which sought to vest the crown of England in the non-existent male heirs of Frances Brandon and her three daughters and no last minute attempt to place Jane Grey on the throne with the express intent of keeping Mary from it. Instead, Edward would have acknowledged his half-brother's position as heir apparent and when Edward finally died on 6 July 1553 England would have faced a very different future, perhaps.

If there had been opposition it would probably not have come from Mary. From an early age she had been taught that the throne of England was the right of the male heir. Her later insistence on her (rightful) title of princess should not be taken as evidence of ambition in this direction. Despite their differences, Mary always maintained her loyalty to Edward as her king and was careful to keep her distance from any sort of plot or political intrigue. This was most noticeable in 1549. During a summer of rebellion the govern-ment's attempts to link Mary with the unrest were not successful. Shortly afterwards, when she was approached to lend her support to a plan to oust the increasingly unpopular Edward Seymour in order to make her regent, she refused to become involved. Katherine of Aragon's daughter was well aware that certain aspects of government were outside the competence of a woman. She expected to be the consort of some foreign prince in a marriage that brought economic and political benefit to her country. The idea that she might rule at all, much less without a husband at her side, would have astonished her.

In 1553 Mary's victory was assured because under the terms of the Act of Succession of 1543 and her father's will she was the legal heir to the throne. However, she and her supporters were in no sense a government-in-waiting. Anyone with any real political ambition had already seen which way the land lay and thrown in their lot with the new regime under Edward. It may be a little cynical to argue that there were perhaps also those who supported Mary, gambling on the fact that she was too middleaged and too racked by health problems to live long or produce an heir. God willing they need only endure her for a short time before they might have Elizabeth. Perhaps it is rather less cynical to claim that there were those who would prefer any alternative to Jane Grey's new husband Guilford, the youngest son of John Dudley, the unpopular Duke of Northumberland, as king. If Richmond had been the designated heir under the terms of his father's last will, then that support would have flocked to him and he no doubt would have exploited it to its full advantage.

There were, of course, others who might have mounted a claim in reaction to the accession of this bonafide bastard. Elizabeth is an obvious candidate, but in 1553 she was still only twenty and a female to boot. In fact, this was a disability shared by all the near blood claimants. They were either, like Margaret Douglas, female, or, like her seven-year-old son, Henry, Lord Darnley, rather too young to stage a coup on their own behalf. There was also always the possibility that another great lord of the kingdom might choose to stand against Richmond. Although these were rather thinner on the ground than in times past â and the death of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk in 1545 removed one dangerous possibility â the combined ambitions of Edward and Thomas Seymour may well have been sufficient to cause him concern. But they would still have needed to muster sufficient support for a coup and there is no guarantee that this would have been forthcoming.

Any attempt to judge what type of monarch King Henry IX might have become must also be pure speculation. The simple answer is probably very much like his father. If part of the duty of a monarch was to look like a king, Richmond certainly met expectations. His wardrobe was positively splendid. A gown of black velvet embroidered with gold, lined with velvet and satin might be paired with matching doublet and hose and topped off with a bonnet of black velvet with a brooch of gold on the cap set with four rubies. The rings on his fingers, collars around his neck or ornamental garters, were all gold set with diamonds, rubies or pearls. His household glittered with gold and silver plate. A large number of pieces, like the silver salt shaped like a unicorn horn and set with pearls, were gifts from his father and Richmond had amassed enough plate from several years' worth of New Year gifts to set a magnificent table.

Like Henry VIII at his accession Richmond was a fine athlete who loved nothing more than hunting and jousting. It is easy to imagine a sense of

déjà vu

as ambassadors and courtiers attempted to keep the king's mind on business, although it is harder to see him as the patron of learning and scholars that William Blount, Lord Mountjoy, saw in his father. Given Richmond's eager pursuit of the arts of war, it is much more possible to see him pursuing as vigorous a foreign policy as his father, keen to secure his own Flodden or Tournai. However, the direction of his campaigns may have been different. Richmond had a warm relationship with Henri, the former duc d'Orléans who now reigned as King of France, although England's tempestuous relationship with Scotland was perhaps always likely to place more strain on Anglo-French relations than a boyhood friendship could hope to offset.

However, Richmond may also have emulated some of his father's less attractive traits. His pursuit of lands and offices suggests an edge of fairly ruthless ambition. His willingness to promote and defend his officers indicates that he was generous to his loyal friends; however his silence over the downfall of Wolsey and Brereton is a worrying hint towards his readiness to put his own interests before anything else. His conscience in matters of religion appears to have been equally malleable. Although his religious education had more in common with Mary than Edward and Elizabeth, and his chapel was certainly traditional enough, he apparently watched the progress of the reformation without a murmur.

Yet Richmond was also universally remembered as charming, gracious and handsome. There were many who lived to mourn his passing. His mother Elizabeth survived him, living until she was about forty years old. Her growing brood of children was little compensation for the loss of her eldest son. If the Earl of Surrey's poetry is a true reflection of his feelings then he too was deeply affected by the loss of his closest friend. A French poet, Nicholas de Bourbon, who had spent some time teaching in England, also wrote a few lines showing that the whole of England grieved for the loss of Richmond. Men like Richard Croke and the French princes spoke with genuine affection for the duke. That Henry VIII appears to have expunged his son from his memory was perhaps not an indication of any lack of feeling, but rather a sign that his grief was such that he could not bear to be reminded of him.

In historical terms Richmond's memory has been overshadowed by the birth of Prince Edward in October 1537. The achievement of his mother, Elizabeth Blount, in presenting Henry with a son has been obscured by the meteoric rise and spectacular failure of Anne Boleyn. As such, neither have attracted the attention devoted to other aspects of Henry VIII's reign. From the chronicler Hollinshed, who had promised to give an account of Richmond in his history of the dukes of the land only never to complete the work, to the modern accounts of Henry's reign which omit all mention of the duke, Richmond has never been seen as a pivotal figure in Tudor history. Yet for Henry VIII he acquired usefulness almost beyond price.

Often his youth was his greatest asset, allowing a style of government â notably at Sheriff Hutton and with the secret council in Ireland â that would not have been tenable under an established magnate. His dual role as an independent magnate and acknowledged son of the king meant that he could embody royal approval in controversial matters, thus saving the king from muddying his own hands. Without the Duke of Richmond, Wolsey's ploy of attempting to woo the daughter of Portugal from the dauphin of France, so that Mary might one day be Queen of France, could not have been put in hand. Richmond also served his father as a diplomat and courtier. He was also good for the king's image. In simple terms, he allowed Henry to demonstrate good lordship by giving out extensive lands and offices without risking the danger of an over mighty subject. More significantly, his presence was Henry's tangible assurance that he could have a son â reassurance for his subjects and an insurance policy that Henry took for granted would always be there.