Battleship Bismarck (10 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

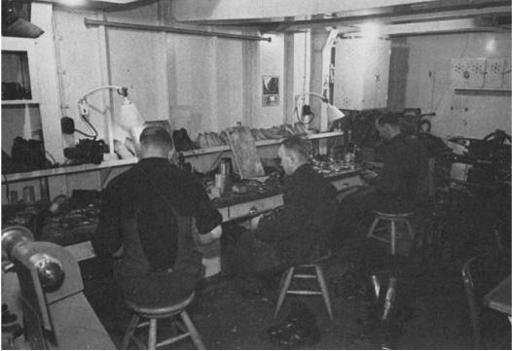

The

Bismarck

had a complete cobbler’s shop. (Photograph from Ferdinand Urbahns.)

During this period, Lindemann lived only to accomplish what he had identified as his primary objective when I reported aboard; to have his ship combat-ready, in terms of both men and material, in the shortest possible time. He had his officers report to him regularly on the progress being made in training the crew and outfitting the various departments, but he did not rely solely on these reports. He was frequently to be seen around the ship, satisfying himself on the spot, attending training, supervising whatever construction remained to be done, asking cogent questions, giving orders, and meting out praise and censure. In addition to these activities, he spent a great deal of time on his paper work, especially reports on questions concerning the ship’s guns, with which he was so familiar. I can still see the clear, steep handwriting in which, in polished terms, he explained his requests and wishes, amended the drafts of other people’s correspondence, or put proposals that would lead to the earlier combat-readiness of the ship into a style that made them irresistible.

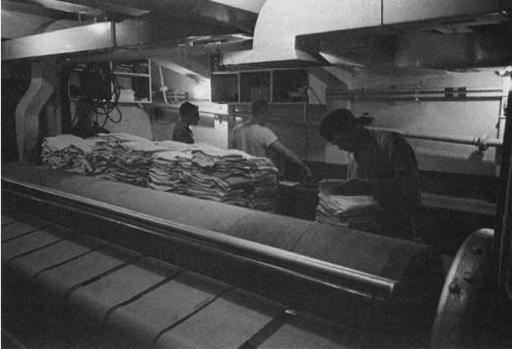

The steam press in the

Bismarck’s

laundry. (Photograph from Ferdinand Urbahns.)

As a rule, Lindemann gave me his orders when I reported to his cabin in the morning. Shortly after I took up my duties, he told me to prepare a schedule of official visits, on which I would have to accompany him, to Hamburg’s civil and military authorities. In due course, we visited the senate of the Free and Hanseatic City in Hamburg’s venerable Rathaus, or town hall, called on the admiral of the Hamburg Naval Headquarters, and on various military commanders and headquarters important to the ship. In August and September 1940 Hamburg was already a target of quite frequent but not very heavy British night bombing raids. Whenever possible, the

Bismarck’s

guns joined in the city’s antiaircraft defenses, and so one of our calls was on the commander of Hamburg’s air defenses, Brigadier General Theodor Spiess, in his roomy offices on the Aussenalster. During visits such as this, wartime security put something of a constraint on the subjects of our conversation, but nevertheless we gained an insight into the morale of official Hamburg. Optimism and confidence in victory were universal. What else, indeed, would one expect, right after the fall of France?

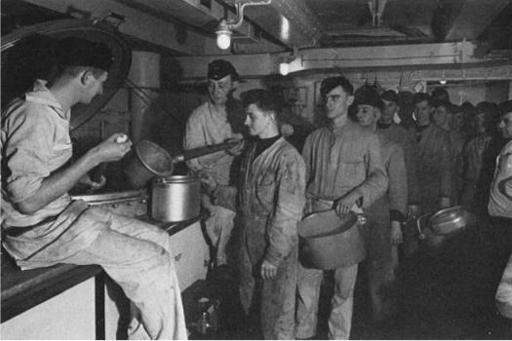

A mess cook ladles food from a giant cauldron into pots that were then carried to the mess decks of the

Bismarck.

(Photograph from Ferdinand Urbahns.)

Most of the visits involved a boat ride across the Elbe from the Blohm & Voss yard. The first time we made this crossing, Lindemann suddenly asked, “Do you know how big the

Bismarck

really is?” He asked this because the

Bismarck

was officially rated at 35,000 tons, and very few people knew her true tonnage. “Well,” I answered, “35,000 tons plus fuel and water, I think.” Not without pride, Lindemann said, “53,000 tons, fully equipped.” When he saw how much that impressed me, he added, “But that is strictly secret information!” Of course, I promised not to divulge it and didn’t until the end of the war.

Members of the

Bismarck’s

crew at mess. The large pot was used to bring hot food from the central galley. (Photograph from Ferdinand Urbahns.)

How far this secrecy extended in practice on board was another matter. There was a machinist chief petty officer who regularly began his briefing on the ship thus: “The

Bismarck

is a movable sea-tank of 53,000 tons. For public consumption and to third parties, the first two numbers change places, so they read 35,000 tons, and that’s what you tell outsiders.”

However, the British government, to whom the

Bismarck’s

construction data were transmitted in accordance with the Anglo-German Naval Agreement in July 1936, had accepted the tonnage figure of 35,000 as entirely true. Even naval attaché Troubridge personally had not doubted it and after the war justified himself by the facade of honest sincerity behind which Raeder had repeatedly assured him of Germany’s firm determination to observe strictly the stipulations of the agreement. Nevertheless, with the political perspicacity characteristic of him, as early as the end of 1936 Troubridge had taken the view and repeatedly reported to London that “when the moment comes, the Anglo-German Naval Agreement will go the way other treaties have before—but not at the moment.”

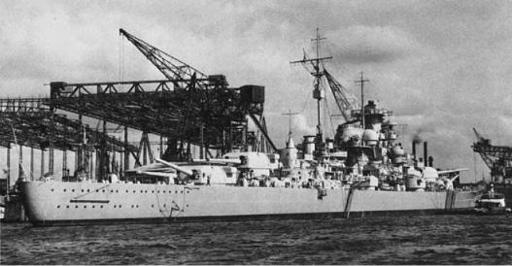

The

Bismarck

made fast to the main outfitting wharf of Blohm & Voss, Hamburg, which she left for the first time on 15 September 1940. After initial trials, she returned to the yard on 9 December 1940 to get her “finishing touches.” She had to remain there until 6 March 1941 because the Kiel Canal was blocked by a sunken ship. (Photograph courtesy of Blohm &. Voss.)

I found Lindemann a thoroughly competent naval officer and gunnery man, one who not only quoted but lived by Prince Otto von Bismarck’s motto,

Patriae inserviendo consumor

(I am consumed in the service of the fatherland). He seemed to be always on duty. When his name came up in the wardroom, it invariably evoked high respect and there was a feeling that it would be impossible to equal his almost ascetic-seeming devotion to duty. Nevertheless, the man had a big heart, a characteristic he was more inclined to exhibit to his men than to his officers, and a radiant smile that greatly contributed to the affection he enjoyed among the crew. Maschinengefreiter

*

Hermann Budich said later: “I completed a year’s building course in the

Bismarck

and was then steward to the Rollenoffizier,

†

Korvettenkapitän

Max Rollmann, who occupied a cabin in the

General Artigas.

Here I encountered many officers, and began to know and esteem Kapitän zur See Lindemann. When one bumped into an officer in the confines of the barracks ship, 90 percent of the time a bawling-out resulted. When the ‘Old Man’ came aboard, he radiated an aristocratic but not overbearing calm. If there was any excitement, he immediately took charge. In short, the ordinary sailor came to trust this man, despite his ‘piston rings.’”

*

*

Lindemann actually said, “Soldiers of the

Bismarck.

” The Germans refer to their naval seamen as “soldiers,” but use “seamen” when referring to men in their merchant marine.

*

According to calculations from her designers (Mr. Otto Reidel), whose records include the construction specifications of both the

Bismarck

and the

Hrpitz

, when the

Bismarck

was completed, her full-load displacement was 50,933.2 metric tons, while the

Tirpitz

was 50,955.7 metric tons.

*

Degaussing gear

*

Seaman Apprentice (Machinist)

†

The Detailing Officer, who assisted the First Officer in distributing the seamen of the ship’s company among the battle stations, as called for by the battle or clear-for-action drills. The composition of the divisions was determined and drill stations were assigned on this basis. Every member of the crew had to be berthed in a space as near as possible to his action station so that he could reach it without interrupting the ship’s traffic patterns.

*

Captain’s stripes

|

The day came for the

Bismarck

to leave the Hanseatic City for the first time and undergo her trials, which were to be conducted in the eastern Baltic. She had been lying with her stern to the Elbe, hut on 14 September 1940 tugs turned her 180 degrees. A day later she slid into the channel and steamed through a mass of ships and launches, past the familiar landscape of the village of Blankenese, to the lower Elbe. How often I had passed this way on ships in peacetime, when the banks were full of people waving friendly greetings. But now it was wartime; the

Bismarck’s

sailing had not been announced, and the banks were empty. Early in the evening we dropped anchor in Brunsbüttel Roads, in order to enter the Kiel Canal the next morning. Naturally, the first time we anchored, I wanted to watch the operation. The anchor chain ran out with what to those who were forward of the navigation bridge sounded like a great roar but, because of the length of the ship, was scarcely audible to those aft. Furthermore, since the hull of the ship remained completely motionless, which is far from the case when a cruiser drops anchor, anchoring must have seemed to the men aft like something that was going on in “another part of town.” After darkness fell, the air raid alarm sounded; the “Brits” were back. Aided by the light of a searchlight ashore, the

Bismarck

joined in the antiaircraft fire. But there was no visible result.