Battleship Bismarck (8 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

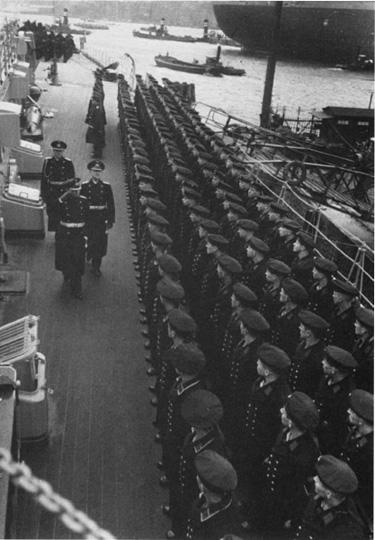

The ensign is hoisted for the first time on the

Bismarck

, formally placing her in commission in the Kriegsmarine. The horizontal and vertical stripes and the Iron Cross in the upper lefthand corner are reminiscent of the white ensign flown by ships of the Imperial German Navy. In the background is the ocean liner

Vaterland

, which was launched earlier the same day. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

“Seamen of the battleship

Bismarck!

*

Lindemann began. “Commissioning day for our splendid ship has come at last.” He called on the crew, on each individual, to do his best to make her a truly effective instrument of war in the shortest possible time, and thanked Blohm & Voss for having worked so hard that she had been completed ahead of schedule. He spoke of the significance of the hour at hand, which demanded a military solution to the fateful questions facing the nation, and quoted from one of Prince Otto von Bismarck’s speeches to the Reichstag, “Policy is not made with speeches, shooting festivals, or songs, it is made only by blood and iron.” After expressing certainty that the ship would fulfill any mission assigned to her, he gave the command, “Hoist flag and pennant!” The honor guard again presented arms and, to the strains of the national anthem, the ensign was hoisted on the flagstaff at the stern and the pennant on the mainmast. Both waved smartly in the wind. The battleship

Bismarck

had joined the Kreigsmarine.

Kapitän zur See Lindemann, followed by the First Officer, Fregattenkapitän Hans Oels, and the author, reviews one of the ship’s divisions during commissioning ceremonies. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

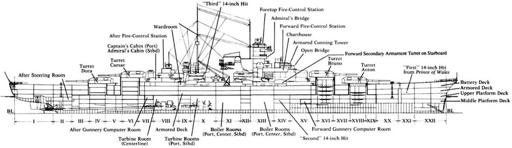

Laid down on 1 July 1936 and launched on 14 February 1939, the

Bismarck

had a net displacement of 45,928 metric tons and a full-load displacement of 49,924.2 metric tons.

*

Her overall length was 251 meters, her beam 36 meters, and her designed draft was 9.33 meters or, at maximum displacement, 10.17 meters.

Of special interest is the fact that, in comparison with most large warships of the period, her beam was relatively wide in proportion to her length. This characteristic ran counter to the prevalent desire for ever more speed, which called for the least beam possible in relation to length. However, the

Bismarck’s

wide beam seemed to work to her overall advantage, because it lessened any tendency to roll in a seaway and, thus, increased her value as a gun platform. It also reduced her draft, which could be important in the shallow waters of the North Sea. Furthermore, it allowed a more efficient use of space, better placement of armor, a greater distance between the armored outer shell and the longitudinal torpedo bulkheads, which protected the ship against underwater explosions, and simplified the arrangement of the twin turrets of the secondary battery and of the heavy antiaircraft guns.

More than 90 percent of the

Bismarck’s

steel hull was welded. As added protection against an underwater hit, her double bottom extended over approximately 80 percent of her length. Her upper deck ran from bow to stern, and beneath it were the battery deck, the armored deck, and the upper and middle platform decks. A lower platform deck ran parallel with the stowage spaces, which formed the overhead of the double bottom, almost throughout. Longitudinally, the ship divided into twenty-two compartments, numbered in sequence from the stern forward.

Armor comprised the highest percentage of the ship’s total weight, some 40 percent, and qualitatively as well as quantitatively it was mounted in proportion to the importance of the position to be protected. The upper deck was reinforced by armor that ran almost its entire length. This armor was only 50 millimeters thick but it provided protection against splinters and would slow down an incoming projectile so that it would explode before striking the armored deck below, which protected the ship’s vital spaces. The armor on this deck was from 80 to 110 millimeters thick and ran longitudinally between two armored transverse bulkheads, 170 meters apart. At the stern, the armor thickened into an inclined plane to protect the steering gear. Between the transverse bulkheads, the ship’s outer shell was covered by an armored belt, whose thickness varied up to 320 millimeters and which protected such important installations as the turbines, boilers, and magazines. Higher up, the armor was between 120 and 145 millimeters thick and it formed a sort of citadel to protect the decks above the armored deck. The two-story forward conning tower, the elevated after section of which served as the forward fire-control station, was also armored with 350 mm on sides and 220 mm on roof.

Since as a weapon system the

Bismarck

was almost exclusively a gun platform, protection of her guns was of the utmost importance. Her main turrets were protected by armor that ranged in thickness from 150 to 360 millimeters. Her secondary armament was less heavily protected; indeed, the relatively light armor in those areas left something to be desired as protection against heavy projectiles.

The arrangement of the superstructure was very similar to that of the

Prinz Eugen

and other German heavy cruisers. There were four decks forward and three aft. The tower mast was on the forward bridge, and atop it were the main fire-control stations for both the antiaircraft gun and the surface batteries.

The propulsion plant, which comprised 9 percent of the total weight of the ship, consisted of three sets of turbines for which twelve high-pressure boilers supplied steam. The plant was designed to provide a top speed of 29 knots at a total horsepower for the three shafts of 138,000, but at the normal maximum of 150,000 horsepower the speed was 30.12 knots. By the time she had been completed, the

Bismarck

was one of the fastest battleships built up to that time.

Her maximum fuel-oil capacity was 8,700 tons, which gave her an operating range of 8,900 nautical miles at a speed of 17 knots, and 9,280 nautical miles at 16 knots. This was a remarkable range for a turbine ship of that day, and it shows that, from the outset, the

Bismarck

was intended for high-seas operations. However, it was some 1,000 nautical miles less than the range of the preceding

Scharnhorst-class

of turbine battleships, and it might be that this relative lack of endurance contributed to the

Bismarck’s

unhappy end.

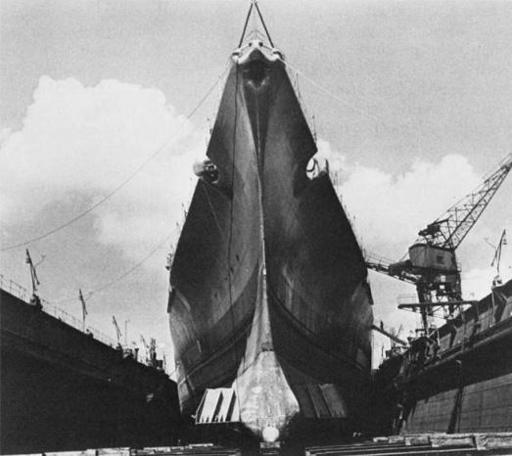

In the course of her construction, the

Bismarck

went into a giant floating dry dock at Blohm &. Voss so that work could be done on her external hull fittings. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.]

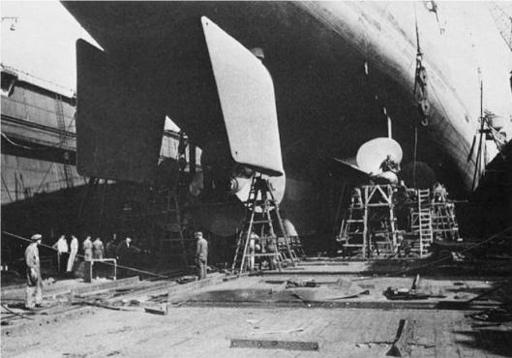

Electric-drive steering gear controlled two rudders mounted in parallel, each with an area of 24 square meters.

A big-gun ship such as the

Bismarck

needed an enormous amount of electrical energy. To supply it, there were four generating plants comprised of two 500-kilowatt diesel generators and six steam-driven turbo-generators. In total, these generators delivered approximately 7,900 kilowatts at 220 volts.

While the

Bismarck

was in dry dock, her three propellers, which were almost five meters in diameter, were installed. The workman sitting on the hub of the starboard propeller gives an idea of its size. In the foreground are the ship’s twin rudders, her Achilles’ heel. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

The battleship’s main armament consisted of four double 38-centimeter turrets, two of which, Anton and Bruno, were mounted forward, and two, Caesar and Dora, aft. Their maximum range was 36,200 meters. For these guns, her normal load was 840 rounds, her maximum load 960, each of which consisted of the shell (weighing 798 kilograms), a primer, and a principal charge. The shells were so heavy that they had to be conveyed from the magazines on the middle platform deck to the turrets by means of a mechanical hoist. Secondary armament consisted of twelve 15-centimeter guns (weighing 43.3 kilograms per shell) in six twin turrets equally divided on either side of the ship. They had a maximum range of 23,000 meters. The normal ammunition supply for these was 1,800 rounds. Antiaircraft defense consisted of heavy, medium, and light guns. As heavy flak, the

Bismarck

carried sixteen 10.5-centimeter quick-firing guns in twin mounts, with a maximum range of 18,000 meters. Sixteen 3.7-centimeter semiautomatic guns in twin mounts provided medium flak, and eighteen 2-centimeter in ten single and two quadruple mounts provided light flak.

Since a battleship is essentially a floating gun platform, a description of the

Bismarck’s

gunnery equipment and procedures may be helpful, especially because these differed from navy to navy. Her surface fire-control system was installed in armored stations forward, aft, and in the foretop. Inside each station were two or three directors. A rotating cupola above each station housed an optical range finder and served as a mount for one of three radar antennas.

The director, which was basically a high-powered telescope, was used to measure bearings for surface targets. In contrast to most other navies, the Kriegsmarine did not mount its directors in the rotating range-finder cupola, but below it, inside the fire-control station. The director was designed like a periscope so that only the upper lens protruded slightly above the armored roof of the fire-control station.

Not only the optical range finders but also the radar sets were used to measure range to the target. German radar had a shorter range and poorer bearing accuracy than the optical equipment. It gave exact range information in pitch darkness or heavy weather, but it was extremely sensitive to shock caused by the recoil of heavy guns. Range and bearing information from directors, range finders, and radar were received in two fire-control centers, or gunnery-computer rooms, which provided continuous solutions to ballistic problems.

Control of the guns was primarily the task of a gunnery officer. His personality, as expressed by his choice of words and tone of voice, could influence the morale of his men. Either the main battery or the secondary battery could be controlled from any one of the three stations, whose directors were brought to bear on a target by two petty officers under the direction of a gunnery officer who observed the fall of shot. In each station, there was a “lock-ready-shoot” indicator whose three-colored lights showed the readiness of the battery, the salvo, and any possible malfunctions in the guns. When the battery was ready, the petty officer on the right side of the director would fire by pressing a button or blowing into a mouthpiece. It was also possible to actuate the firing system from any of the computer rooms.