Battleship Bismarck (3 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

Table of Equivalent Deck Designations

| Kriegsmarine | United States Navy | Royal Navy |

|---|---|---|

Stauung | Tank Top | Tank Top |

Unteres Platformdeck | 3rd Platform | |

Mittleres, Platformdeck | 2nd Platform | Lower Platform |

Oberes Platformdeck | 1st Platform | Upper Platform |

Panterdeck | Fourth Deck | Lower Deck |

Zwischendeck | Third Deck | Middle Deck |

Batteriedeck | Second Deck | Main Deck |

Oberdeck | Main Deck | Upper Deck |

Aufbandeck | 01 Level | Shelter Deck |

Unteres Bruckendeck | 02 Level | Boat Deck |

Unteres Mastdeck | 03 Level | No. 2 Platform |

Oberes Mastdeck | 04 Level | Signal Deck |

Admiralbrucke | 05 Level | Lower Bridge |

| | 06 Level | Upper Bridge |

BATTLESHIP

BISMARCK

|

Sea Battle Between the English and French! Churchill Bombards the French Fleet!

So read the giant headlines in the daily newspapers on Hamburg kiosks. This sensational display told the German public of the bloody attack by a British naval force on French warships lying in the harbor at Oran, Algeria, at the beginning of July 1940. The attack was part of a determined British attempt to prevent the Germans from seizing the French Navy, a threat raised by the French surrender late in June. Nominally, the fleet was under the control of the Pétain government, but most of it had taken refuge in ports outside of France. On the morning of 3 July, a British naval force, consisting of two battleships, a battle cruiser, an aircraft carrier, two cruisers, and eleven destroyers, appeared off the coast of Algeria. Its commander immediately presented the French admiral with an ultimatum to surrender his ships. When the allotted time had expired and the French had taken no action, the British opened fire. Thirteen hundred French seamen were killed that afternoon, and three French battleships were destroyed or damaged. Only the battleship

Strasbourg

and five destroyers managed to escape to Toulon.

As I read the news accounts of this amazing event, I was reminded of the British seizure of the Danish fleet at Copenhagen in the midst of peace in the year 1807. But this attack, taking place in my day and between two states that had been allies until then, impressed me so deeply that I made note of the commander of the task force and ships involved: Vice Admiral Sir James Somerville, the battle cruiser

Hood

, and the aircraft carrier

Ark Royal.

Still, I had no inkling of the role

that within a year this admiral and these ships would play in the fate of the battleship

Bismarck

, to which I, a thirty-year-old Kapitänleutnant,

*

had just been assigned.

In June 1940, when I first saw the

Bismarck

, she was in the Hamburg yard of her builders, Blohm & Voss, awaiting completion and acceptance by the German Navy. Therefore, what I saw was a dusty steel giant, made fast to a wharf and littered with tools, welding equipment, and cables. An army of workmen was hustling to complete the job, while the crew already on hoard were familiarizing themselves with the ship and conducting whatever training was possible under the circumstances.

But under this disguise, the distinctive features, both traditional and novel, of the future battleship were already apparent. There it was again—that elegant curve of the ship’s silhouette fore and aft from the tip of the tower mast—then a characteristic of German warship design that sometimes led the enemy to confuse our ship types at long range. Other things about her were familiar to me because I had served in the battleship

Scharnhorst

, but everything about the

Bismarck

was bigger and more powerful: her dimensions, especially her enormous beam, her high superstructure, her 38-centimeter main-battery guns (the first of that caliber installed in the Kriegsmarine), the great number of guns she had in her secondary and antiaircraft batteries, and the heavy armor-plating of her hull, gun turrets, and forward command-and fire-control station. She had a double-ended aircraft catapult athwartships, another first for the Kriegsmarine, and, as did the

Scharnhorst

and her sister the

Gneisenau

, the new, spherical splinter shields on her antiaircraft stations on both sides of her tower mast.

At first sight of this gigantic ship, so heavily armed and armored, I felt sure that she would be able to rise to any challenge, and that it would be a long time before she met her match. A long life was very obviously in store for her. Still, I thought, the British fleet had numerical superiority, and the outcome of any action would depend on the combination of forces engaged. But questions like that seemed to lie far in the future, as I began my service in the

Bismarck.

I had supreme confidence in this ship. How could it be otherwise?

When my assignment to the battleship

Bismarck

reached me in May 1940, eleven years of naval service lay behind me. I was born in Spandau in 1910, into a family that originated in Baden but some of whom migrated to the east. The profession of arms was a family tradition. My father was killed in action as a major in command of the 5th Jäger Battalion in the Argonne in April 1916; my only brother, who was younger than I and a captain in the Luftwaffe, was killed on 2 September 1939 while serving as a squadron commander in the Richthofen Wing during the Polish campaign.

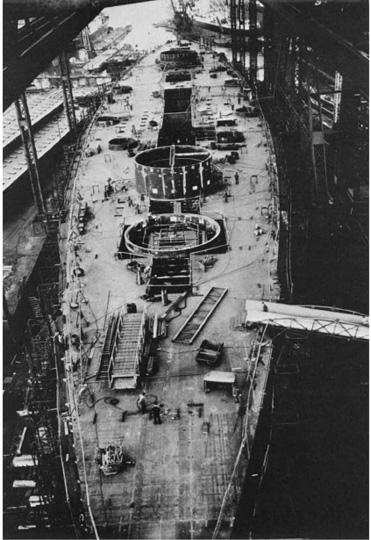

Looking aft over the

Bismarck

on the slipway at Blohm & Voss. She is complete up to her armored deck, where an octagonal hole awaits the installation of the armored barbette for 38-centimeter turret Bruno. The barbettes for turret Caesar and for all six 15-centimeter turrets are in place. (Photograph courtesy of Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart.)

The

Bismarck

is shown almost complete to her upper-deck level. Barbettes for the main and secondary batteries have been installed. (Photograph courtesy of Württembergische Landesbibliotek, Stuttgart.)

In April 1929, I graduated “with excellence” from a classical high school and entered the Weimar Republic’s 15,000-man Reischsmarine. By the time the several thousand applicants had been subjected to rigorous examination, the class of 1929, to which I belonged, numbered about eighty men. A year-long cruise in a light cruiser to Africa, the West Indies, and the United States in 1930 got us accustomed to life aboard ship, and at the same time assuaged our yearning to see the big, wide world, which naturally had played a role in our choice of profession. We then went through the Naval School and took the standard courses on weapons before, towards the end of 1932, we were dispersed among the various ships of the Reichsmarine as Fähnrich zur See.

*

A year later, together with my classmates, I became a Leutnant zur See

†

and then served as a junior officer in a deck division and as range-finder officer in the light cruisers

Königsberg

and

Karlsruhe.

Following my promotion to Oberleutnant zur See

‡

in 1935, I spent a year as a group officer at the Mürwik Naval School, training midshipmen. Early in 1936, I took a course at the Naval Gunnery School in Kiel in fire control, which began my specialization in naval ordnance. There followed two years in our then-very-modern destroyers, first as adjutant to the commander of the 1st Destroyer Division, then as a division and gunnery officer. At the end of these tours, I was promoted to Kapitänleutnant.

In the autumn of 1938 the Oberkommando der Kriegsmarines

§

first sent assistants to the naval attachés in the most important countries. There were very few of these posts and when I was offered one of them, and moreover the important one in London, not only did I feel honored but I felt that an inner longing was being satisfied. I accepted it and took up my post with great pleasure.

The outbreak of the Second World War brought this assignment to an abrupt end and, in October 1939, I began two months’ service as fourth gunnery officer of the battleship

Scharnhorst.

The following month, I took part in the sweep into the Faeroes-Shetland passage, which was led by the Fleet Commander, Admiral Wilhelm Marschall, in his flagship

Gneisenau

, and which culminated in the sinking of the British auxiliary cruiser

Rawalpindi.

Afterwards, the

Scharnhorst

had to go into the yard for an extensive overhaul and I was appointed First Officer of the destroyer

Erich Giese.

As such, I participated in mine-laying operations off the east coast of Britain in the winter of 1939–40 and in the occupation of Narvik during the Norwegian campaign of April 1940. All ten of the German destroyers engaged in this operation were lost, half of Germany’s destroyer force. I had to be given a new assignment and, because of my weapons training, I was appointed fourth gunnery officer, my action station being the after fire-control station, in the

Bismarck

, which was soon to be commissioned. I looked forward with keen anticipation to serving in this wonderful, new ship.