Battleship Bismarck (9 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

The gunnery officer could order a “test shoot,” to find the range, or he could order a series of full or partial salvos. Rather than waiting to spot each splash between salvos of a “test shoot,” he could use a “bracket” to find the target. A “bracketing group” consisted of three salvos separated by a uniform range, usually 400 meters, and fired so rapidly that they were all in the air at the same time. On the

Bismarck

it was customary to fire “bracketing groups” and, with the aid of our high-resolution optical range finders, we usually succeeded in boxing or straddling the target on the first fall of shot. The gunnery officer was aided in spotting the fall of shot by one of the gunnery-computer rooms, which signaled him by buzzer when the calculated time of projectile flight had expired.

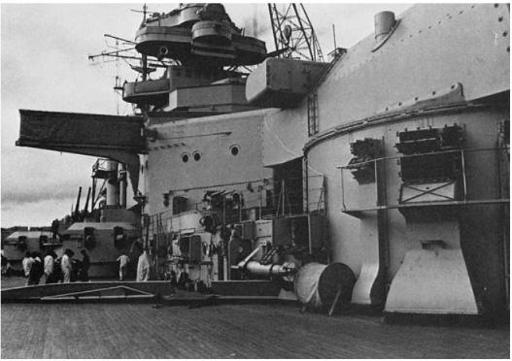

A view of the tower mast and bridges from the forward upper deck, taken while the ship was still outfitting at Blohm & Voss. The platform jutting out from the open bridge was for navigating in such confined waters as canals. It could be folded aft when not in use. Just forward of the two 15-centimeter gun turrets is a group of men in training. In the immediate foreground is turret Bruno. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

Once the range and bearing had been found, the gunnery officer in control would order, “Good rapid.” He could choose to fire full salvos of all eight guns or partial, four-gun salvos fore and aft. In either case, the “firing for effect” was as rapid as possible.

Firing could also be controlled by the individual turret commanders. This allowed great flexibility in case of battle damage. However, in action it was most important for the senior gunnery officer to retain control of the batteries for as long as possible, because central fire control with the help of computer rooms was far superior to independent firing under the control of the turret commanders.

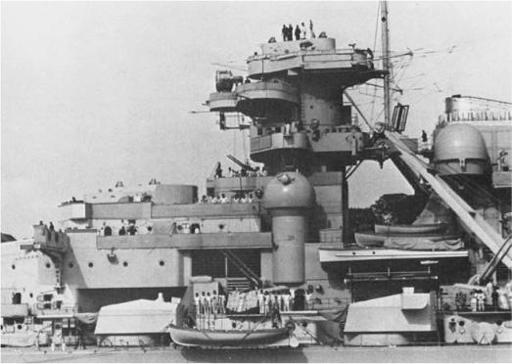

The forward superstructure of the

Bismarck.

The first level at left is the open bridge. Just aft and to the right is the armored conning tower containing the protected wheelhouse and forward fire-control station. On the next level is a twin 3.7-centimeter antiaircraft gun mount. Just above it is the admiral’s bridge. On top of the tower mast is the foretop fire-control station. Two of the three directors in each of these fire-control stations can be seen protruding through the roofs. The rotating range-finder cupolas have not yet been fitted. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

As defense against magnetic mines and torpedoes, the

Bismarck

was equipped with a Mineneigenschutz.

*

This device consisted of a series of cables that encircled the ship inside the outer hull below the waterline. It was supposed to dissipate the magnetic field generated by the ship so that the enemy’s magnetic mines and torpedoes would not detonate.

For reconnaissance, the spotting of shot, and liaison with friendly forces, the

Bismarck

carried four single-engine, low-wing Arado-196 aircraft with twin floats, which also served as light fighters. Two of these machines were stored in a hangar beneath the mainmast, the other two in ready hangars that held one aircraft each on either side of the stack. The planes were launched by means of a catapult located between the stack and the mainmast. This installation ran laterally across the deck as a double catapult, so that launching could be to either starboard or port.

A view of the forward main-battery turrets from the forecastle. Just aft of and above turret Bruno is the open navigation bridge and the armored conning tower. The enclosure with large windows is the admiral’s bridge. Aft of the wave-breaker, to starboard, a detachment of men is assembled. On the wharf, to port, is one of the Blohm & Voss workshops. (Photograph from Bundesarchiv, Koblenz.)

The crew consisted of 103 officers, including the ship’s surgeons and midshipmen, and 1,962 petty officers and men. It was divided into twelve divisions, whose numerical strength varied from 180 to 220 men. The battle stations of Division 1 through Division 4 were the main and secondary batteries. Division 5 and Division 6 manned the antiaircraft guns. Division 7 consisted of what we called “functionaries,” that is, such specialists as master carpenters, yeomen, cooks, and cobblers. Division 8 consisted of the ordnancemen, and Division 9 combined signalmen, radiomen, and quartermasters. Division 10 through Division 12 were the engineers. During our operational cruise, Division 1 through Division 6, reinforced by approximately half of Divisions 7 and 8, occupied every other action station, checkerboard-style. When “Clear for action!” was sounded, the free watch occupied the vacant action stations.

The dark color on the

Bismarck’s

gun barrels is red lead. It was normally applied when the barrels’ gray paint blistered and peeled from the heat of extensive firing and had to be scraped. The rings around the guns hold a cable connecting a coil (visible at the muzzle) to an instrument in the turret which measures each shell’s time of flight. (Photograph from Ferdinand Urbahns.)

The pilots and aviation mechanics we had on board belonged to the Luftwaffe and wore Luftwaffe uniforms. The air observation people were naval officers who were experienced in the recognition and evaluation of events at sea and had been detailed to the Luftwaffe; they served also as radiomen. When we departed on our Atlantic operation, the fleet staff, prize crews, and war correspondents raised the total number embarked to more than 2,200. On 27 May 1941, when the

Bismarck

sank, only 115 of them were saved.

At the time I joined the ship, her entire crew had not yet been ordered aboard. Some sixty-five technical officers, petty officers, and men had been on board since around the middle of April, and sixty or so members of the gunnery department arrived in June. These men were subjected to what was called a building course, the purpose of which was to familiarize them with the ship’s equipment from the keel up. Many of them, when they first saw the

Bismarck

, with her mighty guns and heavy armor-plating, said to themselves, “Well, nothing can happen to me here, this is really floating life insurance!” The petty officers buried themselves in the intricacies of the engine rooms, the weapons, the trunking and valves, then made drawings and prepared lectures for the instruction of the men. Because of the building work that was still going on, the crew was not, at this time, living on board. Most of them were housed in two barracks ships, the

Oceana

and the

General Artigas.

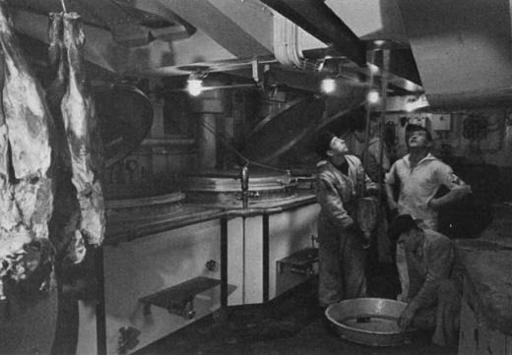

Provisions being brought up to the ship’s galley from the meat locker below. The

Bismarck’s

cold-storage spaces could hold 300 sides of beef and 500 dressed pigs. (Photograph from Ferdinand Urbahns.)

Training began, and the petty officers and their men were assigned their stations. In order to get to know their ship, the men moved through her in small groups, crawling through the hold and ventilation shafts, climbing the bridge and the tower mast, and making themselves familiar with the double bottom, the stowage spaces, the bunkers, and the workshops. Instruction was given on general shipboard duties, on individual areas of competence, and on procedures for clearing for action. So-called emergency exercises began early. We were already at war, so first of all, we had aircraft-and fire-alarm exercises, then damage-control and clear-for-action exercises. These were gone over again and again, always at an increased tempo.

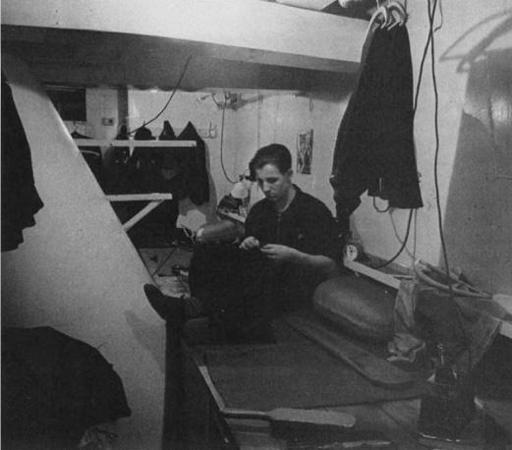

A tailor at work in the

Bismarck

during routine hours. When general quarters was sounded, the tailors, like everyone else, would go to assigned battle stations. (Photograph from Ferdinand Urbahns.)

Signalmen and radio operators, corpsmen, cooks, and stewards began arriving. It was a very young crew; the average age of its members was around twenty-one years, and very few of them had ever been in combat. For many, the

Bismarck

was their first ship. The daily routine was reville at 0600, breakfast at 0630, sweep the decks and clean up at 0715, muster at 0800, then either instruction or practical work at such things as maintenance of the ship and stowing the masses of provisions that were being taken aboard at this time—flags, signal books, binoculars, charts, foul-weather gear, enciphered documents, typewriters, medications, food, drink, everything needed for a ship’s company of more than 2,000 men. The noon break was from 1130 to 1330, after which duties similar to those of the morning continued until 1700, when the evening meal was served. At 1830 the deck was cleaned again, then the duty day came to a close. The call to swing hammocks was sounded at around 2200.