Battleship Bismarck (36 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

In the

Ark Royal

, hasty preparations for a second attack were being made. For one thing, the torpedoes’ magnetic detonators were replaced by contact detonators. There was so much to be done that the originally intended launching time of 1830 slipped. It was 1915 when, under low cloud cover and in varying visibility, fifteen Swordfish

were launched, one after the other, into the wind. Around 2000 they appeared over the

Sheffield.

She directed them, but wrongly at first, because in thirty minutes they were back, without having sighted their target. Directed anew, they flew off again, and the sound of the German antiaircraft fire that soon followed told the

Sheffield

that this time they had gone in the right direction.

|

Daytime on the twenty-sixth passed into early evening. Twilight fell and, as far as we in the

Bismarck

were concerned, the dark of night could not come too soon. In spite of our experience as the object of the enemy’s unerring means of reconnaissance, we were still inclined to feel nighttime brought some protection. Of course, ever since a Catalina rediscovered us that morning, a wheeled aircraft had maintained almost uninterrupted contact. Its presence indicated that a carrier was nearby, but eight hours had now passed and, to our surprise, we had not been attacked. Not having any means of knowing that her Swordfish had lost time by mistakenly attacking the

Sheffield

instead of us, we began to speculate. Could the wheeled aircraft be a reconnaissance plane with extraordinarily long range? Was the carrier too far away to launch an attack? Might we be spared one today, 26 May?

Below, the men’s good spirits had returned and morale was high throughout the ship. Word had spread that an enemy force was about 100 nautical miles astern of us, but unless it was much faster than we were, how could it possibly overtake us? Some men pored over charts and calculated that the next morning we would be 200 nautical miles off the coast, within range of the Luftwaffe’s protection. A report circulated that a tanker was on her way to meet us, so our worries about fuel would be over. Hope sprouted anew. I could not help remembering my conversation with Mihatsch: didn’t we still have a good chance of making St. Nazaire? What was to stop us from outrunning the enemy?

We got the answer to that question around 2030—”Aircraft alarm!”

No sooner had the report that sixteen planes were approaching run through the ship than they were flying over us at high altitude. Then they were out of sight, and the order was given, “Off-duty watch dismissed, antiaircraft watch at ease at the guns.” At ease, but not for long. In a few minutes another aircraft alarm was sounded, and this time it was a different picture. The planes dived out of the clouds, individually and in pairs, and flew towards us. They approached even more recklessly than the planes from the

Victorious

had done two days earlier. Every pilot seemed to know what this attack meant to Tovey. It was the last chance to cripple the

Bismarck

so that the battleships could have at her. And they took it.

Once more, the

Bismarck

became a fire-spitting mountain. The racket of her antiaircraft guns was joined by the roar from her main and secondary turrets as they fired into the bubbling paths of oncoming torpedoes, creating splashes ahead of the attackers. Once more, the restricted field of my director and the dense smoke allowed me to see only a small slice of the action. The antique-looking Swordfish, fifteen of them, seemed to hang in the air, near enough to touch. The high cloud layer, which was especially thick directly over us, probably did not permit a synchronized attack from all directions, but the Swordfish came so quickly after one another that our defense did not have it any easier than it would have had against such an attack. They flew low, the spray of the heaving seas masking their landing gear. Nearer and still nearer they came, into the midst of our fire. It was as though their orders were, “Get hits or don’t come back!”

The heeling of the ship first one way and then the other told me that we were trying to evade torpedoes. The rudder indicator never came to rest and the speed indicator revealed a significant loss of speed. The men on the control platforms in the engine rooms had to keep their wits about them. “All ahead full!”—“All stop!”—“All back full!”—“Ahead!”—“All stop!” were the ever-changing orders by which Lindemann sought to escape the malevolent “eels.”

As though hypnotized, I listened for the sound of an exploding torpedo mixing with the roar of our guns. It could be much worse than it was two days earlier. A hit forward of my station could be tolerated, but what about a hit aft? There was not much distance between me and our sensitive propellers and rudders, and it seemed as though these were our attackers’ favorite targets. We had been under attack for perhaps fifteen minutes when I heard that sickening sound. Two torpedoes exploded in quick succession, but somewhere forward of where I was. Good fortune in misfortune, I thought. They could not have done much damage. My confidence in our armored belt was unbounded. Let’s hope that’s the end of it!

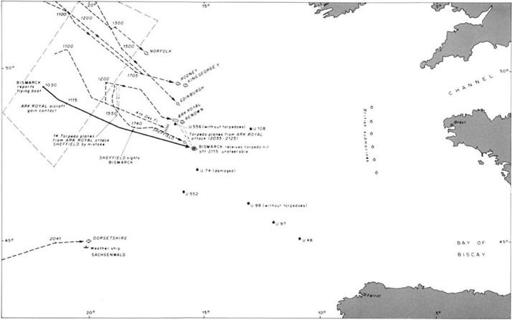

From 1030, German Summer Time, to 2115, German Summer Time, on 26 May. Movements of opposing forces until the fatal rudder hit on the

Bismarck

. (Diagram courtesy of Jurgen Rohwer.)

A Swordfish torpedo-spotter-reconnaissance aircraft returning to the

Ark Royal

after making an attack on the

Bismarck.

The Swordfish carried one 1,600-pound, 18-inch torpedo armed with a charge of 450 pounds of TNT. To deliver an attack, it had to fly at a speed of about 75 knots and an altitude of 50 feet or less. (Photograph from the Imperial War Museum, London.)

Soon after the alarm, Matrosengefreiter Herzog, at his port third 3.70-centimeter antiaircraft gun, saw three planes approaching from astern at an oblique angle, while the talker at his station was reporting other planes coming from various directions. Then, through the powder smoke, Herzog saw two planes approach on the port beam and turn to the right. In no time they were only twenty meters off our stern, coming in too low for Herzog’s or any other guns to bear on them. Two torpedoes splashed into the water and ran towards our stern just as we were making an evasive turn to port.

The attack must have been almost over when it came, an explosion aft.

*

My heart sank. I glanced at the rudder indicator. It showed “left 12 degrees.” Did that just happen to be the correct reading at that moment? No. It did not change. It stayed at “left 12 degrees.” Our increasing list to starboard soon told us that we were in a continuous turn. The aircraft attack ended as abruptly as it had begun.

I heard Schneider on the gunnery-control telephone give targeting information on a cruiser. She was the

Sheffield

, which had come back into view after a long interval. Schneider fired a few salvos, the second of which was straddling. The

Sheffield

promptly turned away at full speed and laid down smoke. The guns of the

Bismarck

fell silent.

Our speed indicator still showed a significant loss of speed because of the turn we were in. Our rudder indicator, which drew my gaze like a magnet, still stood at “left 12 degrees.” At one stroke, the world seemed to be irrevocably altered. Or was it? Perhaps the damage could be repaired. I broke the anxious silence that enveloped my station, by remarking: “We’ll just have to wait. The men below will do everything they can.”

Hadn’t we at least shot down some planes? I had not seen us do so, but we must have. Word that we had shot down several began to make the rounds. How could anyone be so specific, I wondered. Not until years later did I learn that all the Swordfish returned to their carrier.

*

The torpedo hit shook the ship so violently that the safety valve in the starboard engine room closed and the engines shut down. Slowly the vibration of the ship ceased, accentuating individual vibrations. Above, the control station reopened the safety valve and we had steam again. The floor plates of the center engine room buckled upwards about half a meter, and water rushed in through the port shaft well. It did not take long, however, to seal off the room and pump it out.

Casualties in the area of Damage-Control Team No. 1 were kept to a minimum by the foresight of Stabsobermaschinist Wilhelm Schmidt who, when the attack began, ordered his men to cushion themselves against shocks by sitting on hammocks. After the blow that lifted her stern, the ship rocked up and down several times before coming to rest and Schmidt reported to the damage-control center, “Presumed torpedo hit aft.” Inspection by his damage-control parties revealed that the hole blown in the ship’s hull was so big that all the steering rooms were flooded and their occupants had been forced to abandon their stations. The water in those rooms was sloshing up and down in rhythm with the motion of the ship. In order to keep it contained, the armored hatch above the steering mechanism, which had been opened to survey the damage, was closed. But then the after depth-finder tube broke and water rushed through to the maindeck. Apparently because cable stuffing tubes through the bulkheads were no longer watertight and the after transverse bulkheads had sprung leaks, the upper and lower passageways on the port side of Compartment III and the centerline shaft alley were making water. An attempt to pump out the after steering room was delayed by an electrical failure that necessitated switching to a substitute circuit. As soon as that repair had been made, however, it was discovered that the water in the passageway to the steering mechanism had got into the pumps’ self-starters and the pumps were unusable.

Under the supervision of two engineering officers, Kapitänleutnant Gerhard Junack and Oberleutnant Hermann Giese, the damage-control parties, assisted by a master carpenter’s team, went to work. They shored up the transverse bulkhead on the approaches to the steering gear and sealed the broken depth-finder tube. They forced their way through an emergency exit on the battery deck that led to the armored hatch over the steering gear below. A master carpenter and a master’s mate hoped that, with the help of diving gear, they would be able to reach the upper platform deck and there disengage the rudder-motor coupling. Very carefully, they opened the hatch.

Seawater shot up past them, as high as the emergency exit, then was sucked down and disappeared the next time the stern rose in a seaway. Like a falling stone, the stern plunged into the next trough. Once again the water shot up, threatened to overflow the emergency exit, was sucked down on the next wave crest, and disappeared. Giese, the officer supervising the work, was repeatedly called away by questions from the First Officer in the command center. The latter wanted to be informed almost continuously of how things were progressing and to know when the ship could finally resume way. It also appeared ominous that not enough technical personnel were familiar with the layouts of the hand rudder, steering gear, and rudder-motor compartments, that insufficient diving gear was available, and that the volunteers called for did not know how to use it very well. For some, the ship’s abbreviated training period had been too short. Further effort was pointless. There was nothing to do but close the hatch. No one could force his way into the steering plant, much less work there. The attempt had failed.