Battleship Bismarck (34 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

Marinebaurat

*

Heinrich Schlüter suggested that we jettison the forward anchors and anchor chains. His idea was to lighten the forward section so as to adjust the forward trim that we had had since the flooding that began during the battle off Iceland. The ship’s command rejected the suggestion, presumably because it foresaw that the anchors would be essential for mooring in St. Nazaire.

Group West informed the Fleet Commander at about 1930 that the Luftwaffe was ready to cover the approach of the

Bismarck

in force: bombers as far out as 14 degrees west, reconnaissance planes to 15 degrees west, and long-range reconnaissance planes to 25 degrees west; and three destroyers were ready to meet her. The message advised him that the approaches to Brest and St. Nazaire were under strict surveillance and, in an emergency, he would be able to go in to La Pallice. When he passed 10 degrees west longitude, he was to report it promptly.

At about 0430 on 26 May an announcement came from the bridge: “We have now passed three-quarters of Ireland on our way to St. Nazaire. Around noon we will be in the U-boats’ operational area and within the range of German aircraft. We can count on the appearance of Condor planes after 1200.” Joy reigned throughout the ship and morale climbed.

*

Naval Constructor from the Construction Office, OKM (Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine)

|

Like everyone else on board, I knew nothing of the reconnaissance activities in which the Royal Air Force’s Coastal Command was engaged during the night of 25–26 May.

At the beginning of May 1941, seventeen U.S. Navy pilots were sent to Great Britain under the strictest secrecy—the United States was not at war with Germany at this time—and distributed among the flying-boat squadrons of Coastal Command. Their mission was to familiarize the Royal Air Force with the American-built Catalina flying boat some of which had been put at the disposal of the British government under the provisions of the Lend-Lease Act. The arrangement was also to give the American pilots operational experience for the benefit of the U.S. Navy.

With a wingspan of 35 meters, the Catalina had what was at that time the unusually long range of 6,400 kilometers. At 0300 on 26 May, two of them left their base at Lough Erne in Northern Ireland on a far-reaching search into the Atlantic for the

Bismarck.

One of them was Catalina “Z” of Squadron 209. Its pilot was a Briton, Flying Officer Dennis Briggs, its copilot an American, Ensign Leonard B. Smith. Around 1015, in poor visibility and low-lying clouds, Smith saw a ship that he took to be the

Bismarck

, but could not be absolutely certain. Briggs maneuvered the plane into a position for better observation. From an altitude of 700 meters and at a distance of 450 meters abeam, Smith saw the ship again through a hole in the clouds. Was it the

Bismarck!

Minutes later, the Catalina began to transmit, “One battleship bearing 240° five miles, course 150°, my position 49°33′ north, 21°47′ west. Time of origin, 1030/26.”

Flying Officer Dennis Briggs, pilot and aircraft commander of the Catalina flying boat that sighted the

Bismarck

on 26 May 1941. This sighting reestablished the contact that had been lost for thirty-one hours. (Photograph from the Imperial War Museum, London.)

That message showed Tovey how narrowly the

Bismarck

had been missed the previous day: the

Rodney

and her destroyer screen had missed her by some 50 nautical miles, the cruiser

Edinburgh

by around 45 nautical miles. A flotilla of British destroyers had crossed the

Bismarck’s

wake at a range of only 30 nautical miles. Now the

King George V

was 135 nautical miles to the north, the

Rodney

125 nautical miles to the northeast, and the

Renown

112 nautical miles to the east-southeast of the German battleship, which was still 700 nautical miles from St. Nazaire.

|

The

Bismarck

maintained course and speed towards the west coast of France. As the night past had been, the early morning hours of 26 May were quiet. At 1025 Group West radioed Lütjens that our own aerial reconnaissance had started as planned, but that weather conditions in the Bay of Biscay prevented air support from going out. Thus for the time being we could not expect air cover until we were close to shore.

Suddenly, around 1030, a call came from the bridge, “Aircraft to port!” “Aircraft alarm!” All eyes turned in the direction indicated and a flying boat was indeed clearly visible for a few seconds before it disappeared into the thick, low-lying clouds. As soon as it reappeared we opened well-directed antiaircraft fire. It turned away, vanished into the clouds, and was not seen again. We assumed that it was staying in the cover of the clouds so that it could continue to observe us and report our position, preferably unseen. For a while, the bridge considered sending our Arado planes up against the Catalina. But because of the risks that would be incurred in recovering the float planes in such heavy seas, Lindemann would not allow them to be launched.

*

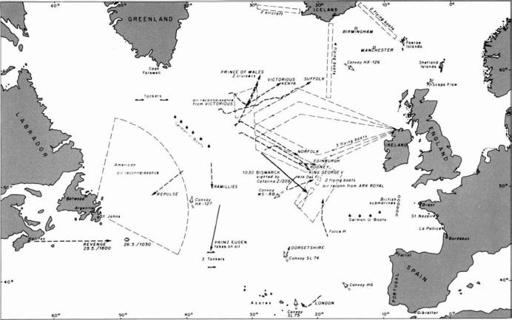

From 1800, German Summer Time, on 25 May to 1030, German Summer Time, on 26 May. After a day without sighting the enemy, the

Bismarck

was rediscovered at 1030, German Summer Time, 26 May. (Diagram courtesy of Jürgen Rohwer.)

Our B-Dienst team speedily decoded the Catalina’s reconnaissance report and at 1156 Group West radioed it to Lütjens as well: “English aircraft reports to the 15th Reconnaissance Group: 1030, a battleship, course 150°, speed 20 knots. My position is 49°20’ north, 21°50’ west.”

We had been rediscovered.

Obviously, the big flying boat had come from a land base a long way away, which led me to assume that it might be a long time before there were any perceptible reactions to its report. But I soon found out that I was wrong. As early as 1200, only an hour and a half after our encounter with the Catalina, Lütjens radioed Group West about the appearance of another aircraft: “Enemy aircraft maintains contact; wheeled aircraft; my position approximately 48° north, 20° west.”

*

A wheeled aircraft! So there must be an aircraft carrier quite nearby. And other, probably heavy, ships would be near her. Would cruisers or destroyers pick up contact before we ran into them? And were we now to experience a new version of our happily ended pursuit by the

Suffolk

and

Norfolk!

We in the

Bismarck

had the realization forced upon us that another page had been turned. After thirty-one hours of almost unbroken contact, thirty-one hours of broken contact had now, perhaps for good, come to an end—an exactly equal number of hours, how remarkable! Did the carrier plane really signify a decisive turn of events? Morale sagged a little among those who could read the new signs.

Of course, we did not know then that the appearance of the carrier aircraft was not simply the visible result of the Catalina’s reconnaissance. We had no idea that the radio signals transmitted by Lütjens the morning before had led the enemy to us. The two signals, the second of which was especially useful to enemy direction-finding stations ashore because of its length, became of interest when the operation was evaluated in Germany. At the time of their transmission, however, they were of no operational consequence. They only helped seal the fate of the ship and her crew.

The dummy stack still lay where it was built on the flight deck. It had not been rigged, and I have not heard a logical reason why not. If it was to serve its purpose, we would have had to set it up when we were out of sight of the enemy, so that the next time they saw us they would immediately think they were seeing a two-stack ship. Instead of playing our trick, we confirmed our identity by firing at the enemy aircraft. As we know today, we even spared him the trouble of making completely sure who we were! So we had decided in advance not to try our ruse or our prepared radio messages, and I could imagine only that this decision had something to do with the attitude of the fleet staff. They probably decided that the overall situation, which they sensed to be increasingly precarious, made it useless to try to camouflage ourselves. There was neither time nor opportunity to ask questions, so I kept my speculations to myself.

*

During the afternoon a Catalina flying boat joined the wheeled aircraft that was holding contact with us. It was the partner of our discoverer, which had earlier been obliged to break off the operation because of its fuel supply. The Catalina circled back and forth over our wake for a long time, out of range of our antiaircraft batteries. Occasionally the planes tried to come closer to us, but each time they were driven off by our flak. The bridge announced that an aircraft carrier was in the vicinity and all lookouts were to pay particular attention to the direction in which the wheeled aircraft disappeared, so that the position of the carrier could be ascertained. The flying boat vanished around 1800 but the carrier plane stayed with us and was soon joined by the cruiser

Sheffield

, which had newly arrived on the scene. At 1824, Lütjens reported the

Sheffield’s

position to Group West, giving her course as 115 degrees and her speed as 24 knots.

At 1903 he radioed Group West: “Fuel situation urgent. When can I count on replenishment?” The question must certainly have puzzled its recipients. Knowing as little as they did about the situation of the

Bismarck

, how could they tell him when and where a supply tanker could be deployed in the midst of the area of operations? It did not become clear until later that Lütjens was only trying to tell them that his fuel supply was critical. In order to keep his transmission brief, he used the so-called short-signal book for encoding, which permitted a report of the fuel situation to be given only in combination with a question about replenishment.