Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (121 page)

As the story emerged, the day before Beethoven had gone out for a walk and, lost in thought, strayed up the towpath of a canal. He kept going until he fell out of his trance and found himself lost and hungry. Trying to figure out where he was and where to find something to eat, he began peering in the windows of houses. This bedraggled Peeping Tom soon caught the attention of the police. “I'm Beethoven!” he told the constable who apprehended him. “Sure, why not?” the constable replied. “You're a tramp. Beethoven doesn't look like this,” and hauled him off. Soon the mayor arrived to apologize and provided a state coach to take him back to Baden in style.

20

Along with his burgeoning creative energy and eccentricity, his duplicitous business schemes also accelerated. In November 1821, having over the past year given his old Bonn friend Simrock repeated assurances that he and only he would have the

Missa solemnis

, he wrote Adolf Schlesinger in Berlin about corrections for the op. 109 Sonata and added, “I am taking this opportunity of writing you

on the subject of the Mass

about which you inquired. This is one of my greatest works and should you care to publish it, perhaps I might let you have it . . . And now let me ask you to keep

this offer secret

.” He had meanwhile persuaded Franz Brentano, Antonie's husband, to advance him Simrock's offer of 900 florins out of Franz's own pocket. Certainly he did not want it to get around that he had offered the piece unequivocally to two publishers. Here he began a long, shabby game over selling the

Missa solemnis

. So far he was only double-dealing. Eventually he worked his way up to quintuple-dealing. And eventually his friendship with Franz broke up over the loan, which Beethoven never paid back.

21

Â

After years of slow and erratic production, the course of 1822 was one of the astonishing periods of Beethoven's life, a creative flowering that would not have seemed possible if he had not done it. He greeted the new year not with optimism but with reports of a painful “gout in the chest.” The condition bedeviled him for months. That summer another visitor, John Russell from England, added his impressions to the mounting record:

Â

Wild appearance . . . eye full of rude energy; his hair, which neither comb nor scissors seem to have visited for years . . . Except when he is among his chosen friends, kindliness or affability are not his characteristics . . . [in a cellar] drinking wine and beer, eating cheese and red herrings, and studying the newspapers . . . he must be humored like a wayward child . . . The moment he is seated at the piano, he is evidently unconscious that there is anything in existence but himself and his instrument; and, considering how very deaf he is, it seems impossible that he should hear all he plays. Accordingly, when playing very

piano

, he often does not bring out a single note . . . The muscles of his face swell, and its veins start out; the wild eye rolls doubly wild; the mouth quivers, and Beethoven looks like a wizard, overpowered by the demons whom he himself has called up.

22

Â

This account sounds suspiciously Romantic, the equivalent of the genius-scowl in so many Beethoven portraits. Earlier reports had his usual expression impassive most of the time, even when playingâexcept for the fiery eyes. But maybe in his age and in the isolation of deafness his feelings had made their way to his face.

Another visitor was Friedrich Rochlitz, a poet and writer who had edited Europe's leading musical journal, the

Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung

, until 1817. Its critics were a frequent target of Beethovenian tirades, but the editor was a fervent if not slavish Beethoven admirer. Rochlitz's recollections of his visits in 1822 shed light less on Beethoven's personality than on his personal style, his way of being in the world that made him endurable and even sometimes lovable, in spite of everything. He was always thinking, soliloquizing, making phrases when he was not making music: “His delivery was absolutely natural and free of any kind of restraint, and whatever he said was spiced with highly original, naïve judgment and humorous fancies. He impressed me as a man with a rich, aggressive intellect and a boundless, indefatigable power of imagination. He might have been a gifted adolescent who had been cast on a desert island and had there meditated on any experience or learning that he might have accumulated.”

Rochlitz enjoyed listening to Beethoven sounding off. There was an ingenuous directness to his rants as he strode around the countryside in his shirtsleeves, his coat slung on a stick carried over his shoulder. “Even his barking tirades, such as those against his Viennese contemporaries, were only explosions of his fanciful imagination and his momentary excitement. They were uttered without any haughtiness, without any feeling of bitterness or resentment, simply blustered out lightly and good humouredly . . . He often showed . . . that to the very person who had grievously injured him, or whom he had just most violently denounced, he would be willing to give his last thaler, should that person need it.”

23

The latter hints that Rochlitz knew he himself was one of the people Beethoven regularly denouncedâenough to earn him one of the composer's nicknames: “Mephistopheles,” after Goethe's elegant demon.

24

In their last meeting Rochlitz noted that Beethoven was suddenly dressed cleanly and elegantlyâhe had begun a campaign to upgrade his wardrobe.

25

Another visitor of 1822 was, as Beethoven knew painfully well, the only composer in the world who in many quarters put him in the shade. Gioachino Rossini's operas were as wildly popular in Vienna as they were in the rest of Europe. Stendhal, who published a biography of Rossini in 1824, declared, “During the last twelve years, there is no man who had been more frequently the subject of conversation, from Moscow to Naples, from London to Vienna, from Paris to Calcutta.”

26

The Italian's first visit to Vienna in April raised the city's ongoing Rossini craze to a frenzy. Every important drawing room in town contended for his presence.

Beethoven and his circle, including Karl, regularly took snipes at this rival. “A pretty talent and pretty melodies by the bushel,” Beethoven said. As for Rossini's celebrated facility, “His music suits the frivolous and sensuous spirit of the age, and his productivity is so great that he needs only as many weeks to write an opera as the Germans need years.”

27

Both quips show that Beethoven had a good sense of the man who between 1815 and 1823 wrote twenty operas full of tunes that stick in the ears.

Rossini admired Beethoven's piano sonatas and quartets, as well as the

Eroica

. He was thirty in 1822, Beethoven fifty-one. The details of their meeting are hazy; it appears that publisher Dominico Artaria first brought Rossini to Beethoven, but he was sick that day and they did not succeed. A second attempt gained him entrance. Rossini was stunned by two things in that visit: the squalor of the rooms and the warmth with which Beethoven greeted this rival who he knew was eclipsing him. There was no conversation; Beethoven could not make out a word Rossini said.

28

But Beethoven congratulated him for

The Barber of Seville:

“It will be played as long as Italian opera exists.” He had also looked over some of the serious operas. “Never try to write anything else but

opera buffa

,” he continued. “Any other style would do violence to your nature.” After a short meeting he sent him off with, “Write many more

Barbers

!”

Rossini left in tears. That night he was the prize guest of a party at Prince Metternich's. He pleaded with the assembled aristocrats, saying something must be done for “the greatest genius of the age.” They brushed him off. Beethoven is crazy, misanthropic, they said. His misery is his own doing.

29

Â

In February 1822, Beethoven sent off the second two of the three piano sonatas Schlesinger had commissioned, opp. 110 and 111. Op. 109 was already engraved. Two months later Schlesinger got a revised finale for op. 111. In fact, Beethoven made a revised final version of one movement in each of the three sonatas.

30

The last of Beethoven's thirty-two piano sonatas wrote the final chapters in his epochal series for the keyboard: his equivalent of

The Well-Tempered Clavier

. Here the divide between his painful and increasingly dismaying life and his increasingly spiritual art reaches an apogee. The last three sonatas mark an end point of his evolution in every dimension: technical, pianistic, expressive, spiritual. Each a distinct individual, the three still share a concern with counterpoint, a juxtaposition of extremes, a climactic finale, and an extraordinary variety combined with extraordinary integration. They combine a constant attention to minutiae in the developing of ideas while often giving the impression of rhapsodic improvisation. At other times they have an almost childlike simplicity and directness.

In character they range from earthy and comedic to ethereal and otherworldly. To repeat: Beethoven rarely compromised the technical for the expressive, or the expressive for the technical. In his late music he still submitted to the old forms established by his forebears, but now the forms are often sunk beneath the surface, still functioning but not breaking the impression of music unfolding in rhapsodic freedom. In the last sonatas, the technical and the expressive together reach an end point unlike anything before or since, perhaps at the end of what music can be and doâas can be said of

The Well-Tempered Clavier

as well.

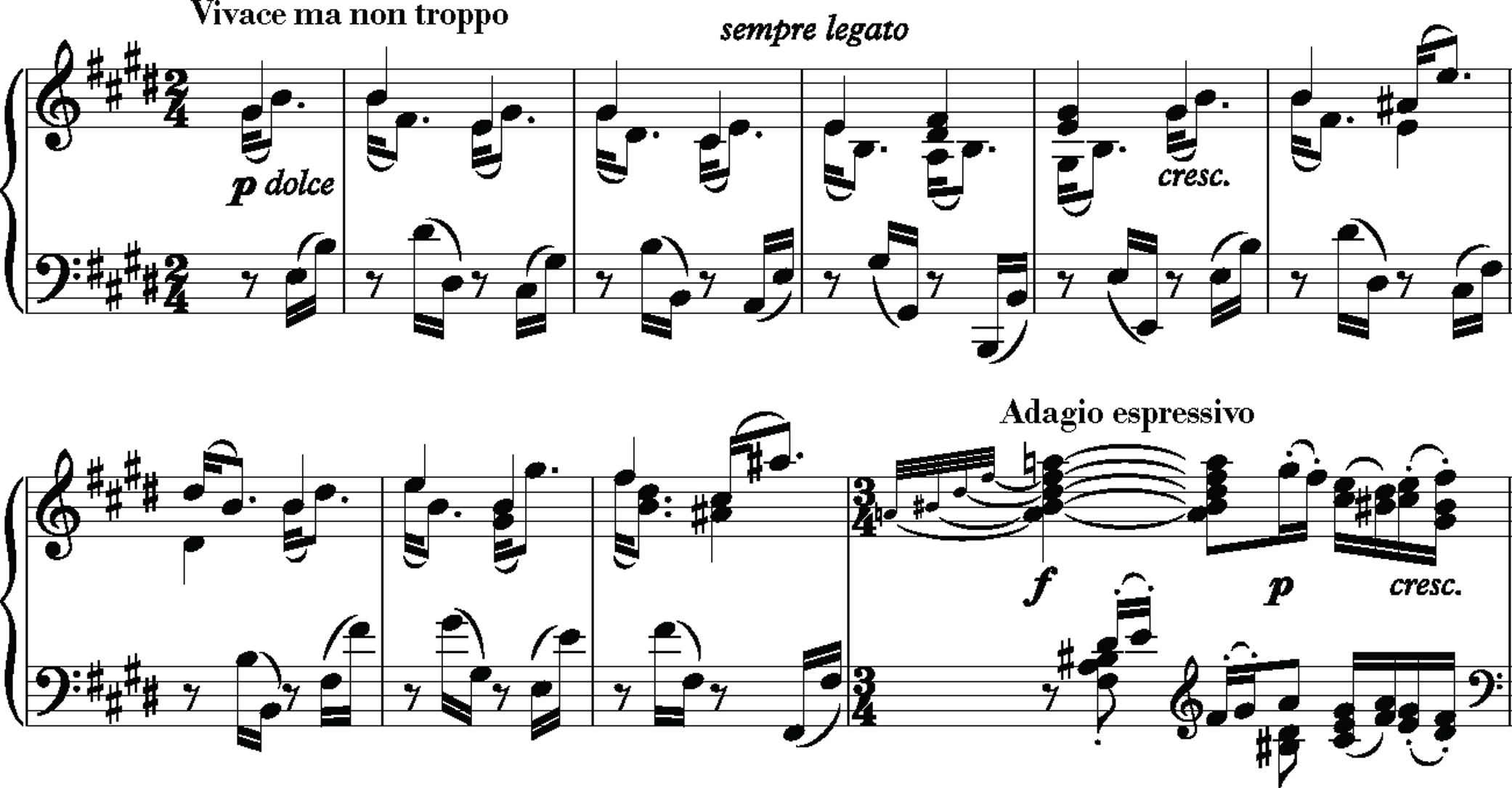

The first movement of the E Major Sonata, op. 109, begins with a blithe, lilting tune marked Vivace ma non troppo. On an open harmony, as if in midthought, the music veers into a mysterious and improvisatory Adagio espressivo, which serves as the second theme of a tightly compressed sonata form:

Â

Â

Â

Â

The leading idea apparently began as a bagatelle written for a piano anthology put together by his friend Friedrich Starke. Another friend, Franz Oliva, suggested that Beethoven use this idea for the commissioned sonata.

31

Now that theme begins the work on an artless and intimate note. In shape, dimensions, and impact, little op. 109 is the anti-

Hammerklavier

. Its opening fillip will be a largely constant presence, its “Scotch snap” rhythm contrasting with the pealing, rhythmically amorphous arpeggios of the second theme. The mercurial character established on the first page will persist throughout. The second theme flows directly (without repeating the exposition) into the development, in which the blithe opening idea becomes gradually vehement; that character phases imperceptibly into the recap. After a much-changed second theme, a quiet and touching coda suggests a joining of the themes. With a

fortissimo

and

prestissimo

eruption, the E-minor second movement breaks out with a driving, fiery-unto-alarming tarantella.

32

Then comes a variation movement for the finale, the theme a solemnly beautiful sarabande, one of the long-breathed themes that exalt Beethoven's late music.

33

It is marked “Songful, with the most heartfelt expression.” Haydn and Mozart had used variations as inner movements of sonatas, even occasionally as a first movement. Now Beethoven lifted variations (as in the

Eroica

) to a weight and finality beyond which nothing needed to be said in a work.

34

In keeping with what came before in the sonata, these variations have mercurial changes of speed and texture and character, from introspective to jovial to Baroquely contrapuntal.

In the final variation the music gathers into a shimmering texture of trills, conjuring something on the order of a divine radianceâsay, Kant's starry sky. The trills gather slowly to an ecstatic climax, then the finale concludes with a simple recall of the theme, the effect of which summons a future poet's line that we return from a journey to where we began and know the place for the first time.

35