BELGRADE (2 page)

Authors: David Norris

It was bombed the last time in spring 1999, when the government was in the hands of Slobodan Milošević, the only remaining communist leader in south-eastern Europe. NATO’s air forces carried out the bombardment during a three-month war with the ruling regime, from which the Serbs freed themselves by a peaceful revolution in October of the following year. The foreign traveller visiting Belgrade in 2007 might not notice the traces of that dramatic campaign unless his attention is turned to the buildings waiting for renovation—of which not many are left. But he may be interested in the narrative behind the buildings bombed by NATO, which now look like new and have become symbols of Belgrade’s survival in the period known as “the time of transition”.

One of these buildings is the slender, green-blue, glass skyscraper which the visitor cannot fail to see whether taking a bus or taxi from the centre of Belgrade, over Branko Bridge on the Sava toward New Belgrade, or from New Belgrade in the opposite direction toward the centre. It stands alone in apparent supremacy over its surroundings near the crossroads of the two boulevards named after the two scientists, Mihailo Pupin and Nikola Tesla. The skyscraper, now in private ownership, is called the Confluence Business Centre and houses the management boards of several large corporations. It used to be, before it was targeted in April 1999, the hub of Slobodan Milošević’s political power and party organization, better known as the Building of the Central Committee.

From his windows facing south-east, the august master had a wonderful view over the junction of the two rivers, over the fortress in Kalemegdan Park on the opposite bank of the Sava, sitting on its rocky outcrop above the confluence as it has done for centuries, and over Belgrade, a modern conurbation astride the remains of ancient settlements put here by Celts, Romans, Bulgars, Magyars, Serbs, Turks and Austrians. From his offices looking north-west, he could watch the whole of New Belgrade, the city’s most populous borough, where building began only after the Second World War when Josip Broz Tito began his 35–year presidency of socialist Yugoslavia. This swarming district has been transformed into interwoven strips of modern architectural and urban structures, tall buildings and broad avenues, piled up without any particular order, attractive in their own way, on the level surface of what was once the low-lying Pannonian plains.

New Belgrade has also been witness to the many social and political changes that have occurred in the city during the last sixty years. It was built slowly, over decades, in the spirit of the anonymous architectural style of Socialist Realism, on land which was mostly sand and mire. It was considered a gloomy dormitory for the many thousands of people who came after the Second World War from the regions to the capital city of the new socialist state to be schooled here, to find work and to stay.

But for some time, and especially since October 2000 when Serbia’s democratic forces took control of government, those who live here no longer look upon New Belgrade as a dormitory—and with good reason. They now see it as a workshop in which a more modern way of life is being produced, circulated and exchanged in an ever increasing tempo. The transformation has been huge and obvious. Life here teems on the wide and long paths beside the Sava and Danube, on the floating restaurants moored one after the other, especially in the afternoons and evenings. The young and the not-so–young, from New Belgrade and elsewhere, find their favourite meeting points and places for entertainment. The people of New Belgrade have again fallen in love with their rivers, whose banks were empty in the 1990s as they echoed to the sound of shooting, explosions and violent clashes between different political factions, particularly under the night sky. The cost of flats and commercial property in the area is now rising at a dizzy pace year on year. With its broad boulevards, hotels, Serbian and foreign banks, modern shopping centres, boutiques, restaurants, markets, greenbelt space and avenues of trees, sports halls, private universities and clinics, New Belgrade has suddenly become a very desirable place to work, live, mix and socialize.

In young Belgrade slang, you often hear as a mark of respect for a friend’s success, “He’s living like a king over on New-side!” The word Newside in this complimentary phrase means New Belgrade. And yet it also carries an ambiguous subtext about the part of town where money is quickly made and by means which are not always exactly honest. Your own money and your own flat represent an ideal goal for young people in today’s Belgrade; not easy to achieve in a world where employment is difficult to find.

Not long ago, a taxi driver, a man in his early thirties, told me of his experience while driving me to the city centre from New Belgrade. He graduated in medicine over five years ago, he said, and then did the usual things: some voluntary work as a doctor and his military service. After a lot of looking around, replying to adverts and waiting, he finally managed to get a job as a doctor in a small town just over a hundred miles from Belgrade and he was very happy. But his happiness did not last long, for less than a year later he had to leave the job he loved. He was not bothered that he had a long daily commute to and from work, nor that he often worked tenor twelve-hour shifts. But he could not reconcile himself to his doctor’s salary not providing enough for his small family to live on for even ten days in the month. He was forced to make a crucial decision: he left the medical profession for which he had studied eight years, took financial help from his father to buy a new car, and became one of several thousand Belgrade taxi drivers. He was not dissatisfied with his lot, now earning three to four times more than when he was a doctor and with more free time to spend with his family.

I listened to his story, not at all unusual by today’s standards in the capital, while the young doctor skilfully squeezed his taxi in and out of the three lanes of modern cars, creeping along in the late afternoon from New Belgrade toward the centre of town. The traffic was thick and almost at a standstill at that time of day, for only three bridges on the Sava link the old part of town, the megalopolis which has remained in the Balkans, with the new part which vaulted over the river and spread out to merge with the former Austro-Hungarian border town of Zemun.

If New Belgrade bears witness to the great changes that have occurred in the decades since the Second World War, old Belgrade nurtures its memory of past centuries and fallen empires in the many layers of earth on which it has survived for over two millennia. The city authorities have paid particular attention to returning to the capital the shine of its former glory, dulled and damaged in the last years of the previous regime.

The Romans put down the first markers at the end of the last century before Christ. The famous fourth Roman legion of Flavius captured the rocky heights above the confluence of the Sava and Danube, and the Celtic settlement which they called Singidunum, the fortress of the Singi. They quickly discovered that it provided a remarkable watchtower over the rivers, marshes and plains to the east and north, and over the hills and forests to the south and west. Unsurpassed builders, as well as excellent soldiers, the Romans established their military camp at today’s Kalemegdan Park and built roads leading into the interior of the land to the east and south. They used the roads and the aqueducts they placed alongside them for a full three-and–a-half centuries, for as long as they ruled Singidunum, which became a rich and prosperous provincial town, until the fall of the Roman Empire.

The later conquerors of the Belgrade fortress did not change the lines of those first Roman roads; at least, this is the story that Belgrade’s urban planners like to tell. Some historians say that the Turks, in their campaign to drive a wedge into Europe, captured Belgrade in 1521 after many unsuccessful sieges and used the roads that the soldiers and slaves of mighty Rome had cut and paved. The story goes that the line of one such road, probably Singidunum’s main street, has been preserved more or less to today. It is the one called in the vocabulary of town planners and other informed citizens the Belgrade ridge and passes through the very centre, dividing the eastern slope which drops down to the Danube from the western slope facing the Sava.

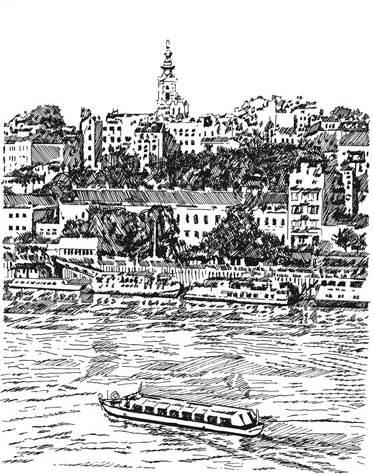

If he likes a walk, our visitor might take in the most important part of the ridge on foot and get to know the centre of contemporary Belgrade. Were I his guide, I would take him first to the plateau of the fortress at Kalemegdan, where the monument to the Victor stands, the symbol of the city and the work of the Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović. A most beautiful view unfolds from the plateau over the waters of the great rivers, the Sava and the Danube, which join at the foot of Kalemegdan, over the Great War Island covered in thick undergrowth, over the plains toward Banat and the east, on the left bank of the Danube, and over New Belgrade to the west, on the left bank of the Sava. All the conquerors and rulers of Belgrade have enjoyed this view in both the morning and evening light, as have the people living here over the last 2,000 years, with the occasional chronicler noting down his wonder at the beauty of the sight. New Belgrade, of course, was nowhere on the horizon before the second half of the twentieth century; in its place was a dark and immeasurable marsh above which, so travellers wrote in their journals, the setting sun presented a surreal scene.

Passing through the park from the fortress which the Turks called

Kale-megdan

, the fortress-on–the-battlefield, our visitor would arrive at Knez Mihailo Street, where the ridge begins. While we step along this route, on which the paving stones cover the remains of the Roman settlement buried deep below, I would tell him details from the history of the houses in the street, one of the oldest in Belgrade. Most of them were built in the nineteenth century by wealthy Serbian merchants, many of whom were also public-spirited philanthropists.

Down Knez Mihailo Street we would soon come to Terazije. The name of the street means, in Turkish, an apparatus for measuring water, a kind of oriental water meter. We could stop to catch our breath in the old and respectable Hotel Moskva, built with Russian capital at the turn of the twentieth century, but perhaps not. We would, of course, continue along King Milan Street, once called Marshal Tito Street, past the crossroads “At the London” and on to the new, elegant building of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre. Then, once across Slavija Square, with its throngs of circling traffic, we would climb to the Vračar plateau. There are two churches here, one large and new, the other smaller and older, both dedicated to St. Sava, sharing the space with the National Library. A monument stands in front of them, just as one stands on the Kalemegdan plateau. This memorial is in honour of Karađorđe, leader of the First Serbian Uprising at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when the idea of the modern Serbian state was formed.

The two statues, the Victor and Karađorđe, placed on these two raised sites imbued with almost mythic status in Belgrade eyes, at Kalemegdan and Vračar, mark the beginning and end of the Belgrade ridge. It is the route along which all armies have had to pass for two millennia, as they advanced and retreated, in victory or defeat, preparing for great sieges and battles, from the time of the Romans to the First Uprising, from the barbaric invasion of the Huns in the fifth century to the even more barbaric bombing of Belgrade by the Third Reich in April 1941. Every evening in autumn 1996 and winter 1997 tens of thousands of citizens of Belgrade, young and old, in good health or sick, celebrated their resistance to violence and madness, scorned Milošević’s terror and protested by peacefully marching from Kalemegdan to Vračar, and from Vračar to Kalemegdan, from the Victor toward Karađorđe, and from Karađorđe toward the Victor, along the line of the old Roman road.

Our traveller, using his imagination, may even feel this line under his feet as he slowly returns along the Belgrade ridge to his hotel. He will undoubtedly be somewhat bewildered by this whirlwind of past and present times in which he has unexpectedly found himself, but which, now as always, blows with the clouds over the gateway to the Balkans.

Svetlana Velmar-Janković

R

EADING THE

C

ITY

A city undoubtedly reflects the mentality of the nation which conceives, and plans, and builds it. Viewed in this light, mere bricks and mortar assume a psychological interest, and are seen as the tangible embodiment of ideas, to be judged according to their practical utility and esthetic value. Thus, the design of a school building, a church, or a house tells its tale more plainly than any words could do.

Despite riches or poverty, the spirit and aspirations of a people are welded into every construction—be it high or low—which meets the eye. This is particularly the case in Belgrade, where the history of the country for several decades back can be traced in the various stages of architecture prevalent in the town.

Lena A. Yovitchitch,

Pages from Here and There in Serbia

(1926)