Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (13 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

No one ever figured out that each of those trips coincided with another stagecoach robbery. In fact, there was not a lot of sympathy for Wells Fargo. Many people believed it was just another big company taking advantage of hardworking people. Some stagecoach robbers were glamorized; they were seen as brave bandits robbing the rich and … well, robbing the rich.

Bowles often waited months before staging another heist. Later he claimed that he stole only “what was needed when it was needed.” Those robberies took careful planning: Because he was afraid of horses, he couldn’t ride, so he had to walk to the scene and then walk away

after the job was done. The robberies almost always took place on the uphill side of a mountain, because the horses had to slow to pull the load. And although no one knew it at the time, the rifle he carried was old and rusted and probably wouldn’t have fired even if he had loaded it, which he did not.

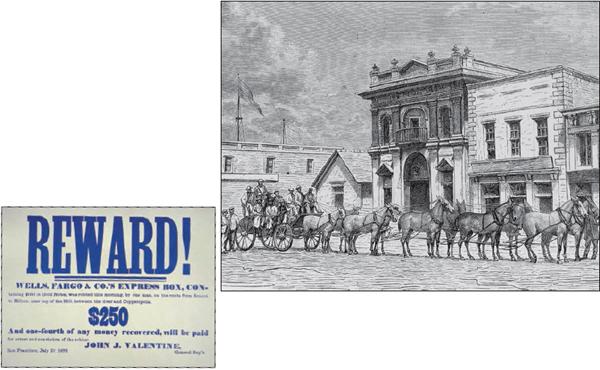

Black Bart’s success in robbing Wells Fargo stagecoaches eventually led the company to offer a reward—and when that failed, the company hired private detective Harry Morse, “the Bloodhound of the West,” to track down the bandit.

The second robbery took place more than five months after the holdup on Funk Hill. Once again, the driver reported a lone holdup man, with three armed accomplices hiding among the rocks. When investigators arrived at the scene, they found the sticks still in position.

Almost eighteen months passed before Bowles’s next crime. In the interim, he had accepted a teaching position in Sierra County. At that time the school year was only about three months long, and that job probably provided an acceptable diversion for him. Supposedly he was well liked by his students; he was known for reciting poetry and quoting Shakespeare, especially

Henry V.

When not robbing stages, Bowles lived as a socialite in San Francisco.

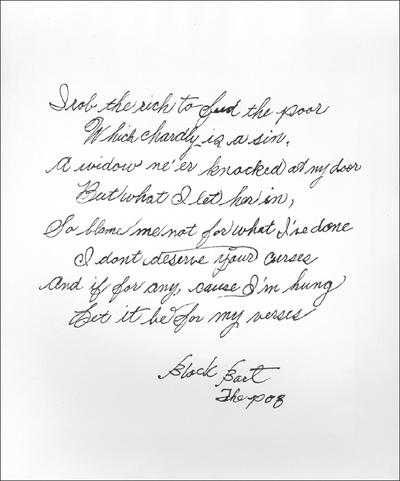

At first, Detective Hume was so busy with other matters that he took little notice of these sporadic holdups. But that changed after Black Bart’s fourth crime, on October 2, 1878. His method hadn’t changed, but for the first time he left a clue. Investigators found a poem in the broken strongbox:

I’ve labored long and hard for bread,

For honor and for riches

But on my corns too long you’ve tread

You fine-haired sons-of-bitches

It was signed

Black Bart, the P o 8.

A day later another stage was robbed. Once again a poem was left at the scene:

Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat

And everlasting sorrow

Yet come what will, I’ll try it once

My conditions can’t be worse

And if there’s money in that box

’Tis money in my purse

Once again, it was signed

Black Bart, the P o 8.

The audacity of the robber who left poems at the scene quickly attracted the attention of newspaper editors and dime novelists, and Black Bart, the Gentleman Bandit, captured the fancy of the American public. All this publicity naturally brought him to the attention of James Hume. Wells Fargo’s analysis of the handwriting suggested a man who had long been employed in clerical work. An eight-hundred-dollar reward was posted for information leading to his capture, and detectives confidently announced he would soon be brought to justice. But the robberies continued without indication that detectives were closing in.

In 1880, Hume finally made an arrest in the case, but it was quickly discovered that the man they arrested actually had the perfect alibi—he had been in prison when several of the robberies occurred.

The fact that Black Bart left his own poems, signed “the P o 8,” at the scenes of his crimes attracted national attention—although his reason for doing so was never determined.

In fact, no one had the slightest idea why this bandit left poems at these crime scenes, nor why had decided to call himself Black Bart, nor even what his signature, “the P o 8,” meant. Only years later was it revealed that the name had been taken from a dime novel published in 1871 entitled

The Case of Summerfield.

The book, which had been reprinted in the

Sacramento Union

soon after its initial publication, featured a robber named Black Bart, a villain who dressed all in black, had long, wild, black hair, and robbed Wells Fargo stagecoaches. Supposedly the story was based on the true exploits of Captain Henry Ingraham’s Raiders, a group of Confederate soldiers who robbed Wells Fargo’s Placerville stage of as much as twenty thousand dollars to purchase uniforms for new recruits—and left a receipt for the theft. There is some evidence that James Hume was involved in tracking down those soldiers and arresting them. If it was true that Hume was involved in that case, then Bowles might have picked that name to taunt him:

You caught them but you can’t catch me.

Bowles never revealed the meaning of his signature, “the P o 8.” Some historians believe it meant simply “the poet,” honoring Bowles’s love of poetry, while others suggest it referred to “pieces of eight,” meaning booty taken by pirates, and was meant to honor the greatest pirate of the Caribbean, Bartholomew “Black Bart” Roberts, who captured more than four hundred ships before being killed in battle.

For more than a century, criminologists have debated why Black Bart left the poems. Maybe the best explanation is that he wanted people to know that he had outsmarted the great Wells Fargo; he wanted to rub the company’s nose in the dirt trails used by their stages. At the same time, he apparently took pride in the fact that no one ever got hurt during his holdups. He was the perfect gentleman robber: He was unfailingly polite, he never took anything from passengers, and he never used foul language. In fact, to reassure their passengers, Wells Fargo issued a statement pointing out that “[he] has never manifested any viciousness and there is reason to believe he is averse to taking human life. He is polite to all passengers, and especially to ladies. He comes and goes from the scene of the robbery on foot; seems to be a thorough mountaineer and a good walker,” then added, “[I]t is most probable he is considered entirely respectable wherever he may reside.” Although that statement may well have calmed passengers, it also helped to make Charles Bowles’s Black Bart into a romantic legend.

It was after his fifth robbery that authorities discovered their first real lead. Investigators found out that following the holdup, a stranger on foot had stopped at a farm and paid for a meal. The farmer’s teenage daughter described him as having “[g]raying brown hair, missing two of his front teeth, deep-set piercing blue eyes under heavy eyebrows. Slender hands in conversation, well-flavored with polite jokes.” It wasn’t much, but for the clue-collecting Hume it was a beginning.

The robberies continued through the early 1880s. Several stagecoach drivers reported actually having pleasant conversations with the bandit during the holdups. In 1881, for example, Horace Williams asked him, “How much did you make?” to which he replied, “Not very much for the chances I take.”

That so many people considered this thief a hero continued to rankle Detective Hume, and he committed considerable resources to the job of catching the elusive robber. He hired the sixty-man detective agency run by the renowned San Francisco detective Harry Morse, “the Bloodhound of the West,” and assigned that company to work on this case. Hume also personally visited the sites of many robberies and diligently scoured the area, looking for the smallest clues. At several of the locations, Hume’s team found the robber’s abandoned camp, which indicated he had waited there patiently, sometimes for several days, for the stage to arrive.

Bowles’s first close call came near Strawberry, California, in July 1882, when he attempted the biggest job of his career. The Oroville stage was carrying more than eighteen thousand dollars in gold bullion, although it isn’t known whether he was aware of that. But perhaps because that

gold was on board, Hume had assigned a shotgun-armed guard to ride next to the driver. Black Bart suddenly appeared in the middle of the trail and took hold of the horse, which bolted, and the coach ran off the road. The robber’s attention was diverted, so he failed to see armed guard George Hackett lift his shotgun and let loose a volley. The buckshot lifted Bowles’s bowler off his head, grazing his scalp. Bowles had no desire—or ability—to shoot back; instead, he disappeared into the brush, leaving his bloodied hat lying in the dirt. The robbery had failed, but he had escaped. By the time a posse got there, he was long gone and had left no other evidence.

Bowles continued to lead two completely different lives: one in San Francisco, where he was Charles Bolton, a man of leisure and wealth, a socialite who slept comfortably on clean sheets and was always welcomed in the better establishments of the city; the other in the wilderness, where he camped alone as he waited for the next stage, sleeping on the hard ground, confronting the elements, eating sardines out of tin cans. Although he subsisted mostly on his ill-gotten gains, he did invest some money in several small businesses that apparently returned a small profit.