Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (12 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Applying our moral standards to a man who lived in and helped shape a different time in our history is an impossible chore. Perhaps the only conclusion to reach is that by his courage and character he helped create this nation. Upon his death, an army officer who had served with him wrote what is perhaps the most fitting description: “Kit was particular to himself. No such combination ever existed in a man before … he united the courage of a Coeur de Leon, the utmost firmness, the strongest will and the best of common sense. He could weep at the misfortunes or sufferings of a fellow creature, but could punish with strictest rigor a culprit who justly deserved it.”

BLACK BART

The Wells Fargo & Company stagecoach was rumbling down the rugged Siskiyou Trail in November 1883, making about ten miles an hour. As the stage slowed to begin the steep climb up Funk Hill, not far from the aptly named copper-mining town of Copperopolis, a man dressed in a long white linen duster and a bowler hat, his face covered with a flour sack with holes cut out for his eyes and mouth, similar sacks covering his feet, and holding a double-barreled twelve-gauge shotgun, stepped out from behind a rock onto the trail. The driver, Reason McConnell, immediately began reining in his team. He knew instantly what was going on: He was being held up by the most famous stagecoach robber in the West, Black Bart.

The robber blocked the coach wheels with rocks to prevent the driver from making a run for it, then ordered McConnell to throw down the strongbox, a big, green, locked wooden box with metal bands around it, which often carried gold or coins from miners. On this trip, the Wells Fargo stage was transporting 228 ounces of silver and mercury amalgam, worth about four thousand dollars, and five hundred dollars in gold dust and coins. McConnell replied that he couldn’t throw down the box because the company had begun bolting it to the floor inside the stage to prevent robberies. Black Bart told the driver to climb down from his seat, then made him unhitch the horses and walk them down the hill. By the time McConnell was several hundred yards down the trail, the robber was hacking at the box with an ax.

What Bart did not know was that McConnell had been carrying a passenger, nineteen-year-old Jimmy Rolleri, whom he had dropped at the bottom of Funk Hill to do some hunting while the stage made the difficult climb. Rolleri was planning to catch up at the other end. McConnell found Rolleri and told him the stage was being robbed. The two men hustled back up to the top of the hill just in time to see the robber Black Bart climbing out of the stage lugging the strongbox. Grabbing Rolleri’s rifle, McConnell began firing. Once! Twice! He missed. Missed again! Bart raced for the thicket. Rolleri reclaimed his rifle and fired into the undergrowth. Twice more. This time, the robber stumbled. He was hit. He regained his footing

and disappeared into the thick brush. The two men followed cautiously, knowing an armed and wounded bandit was dangerous. They pursued a trail of bloody droplets until it disappeared. Once again, Black Bart was gone.

But this time he had made a mistake.

Between 1875 and 1883 the mysterious rogue known across the nation as Black Bart, “the Gentleman Bandit,” held up twenty-eight Wells Fargo stagecoaches in northern California. His pattern never varied: He robbed only Wells Fargo coaches, he was always alone, he never fired a shot or made threats, and he always escaped on foot.

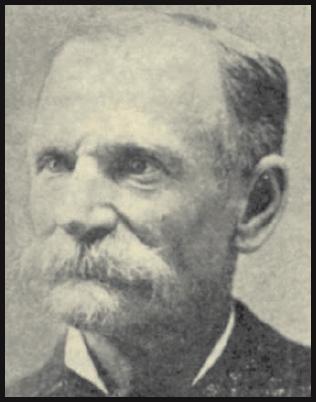

When the stagecoach robber Black Bart was finally identified and arrested by detective James B. Hume in 1883, he turned out to be a most unlikely suspect. The story begins in John Sutter’s sawmill, on the south fork of the American River in northern California, when Sutter’s partner, James Marshall, discovered a few flakes of gold. That marked the beginning of the American gold rush, and during the next seven years more than three hundred thousand men caught gold fever and rushed to the area to find their fortunes. Among them was twenty-one-year-old Charles Bowles, who had been born in Norfolk, England, and brought to America as a young child. Bowles and his two brothers had left their home in upstate New York and crossed the continent to pan for gold. At just about the same time, young James Hume and his brother left their home—coincidentally also in upstate New York—carrying with them the same dreams as Bowles. The difference was that Charles Bowles failed completely—and both of his brothers died in the effort—while Hume was able to eke out a living from his claim.

By 1860, Bowles had married and was living on a small farm in Illinois. In 1862, he volunteered with the 116th Illinois Regiment and ended up serving for three years under General William T. Sherman in the March to the Sea. Although many soldiers served in the cavalry, that was not the right assignment for him: “Whistling Charlie,” as he was known, was evidently afraid of horses. He apparently served with valor, seeing action in numerous battles, including the bloody Battle of Vicksburg—where he reportedly was seriously wounded—and by the time he was discharged in 1865 he had risen to the rank of lieutenant.

Like so many other soldiers who came home from the war, he found it difficult to return to life on the farm. In 1862, miners working Grasshopper Creek in Montana made a major strike. At the end of the war, a second gold rush began, and once again Bowles couldn’t resist it. Apparently he set out on foot for the West, covering as many as forty miles a day, walking all the way to Montana. When he finally got there, he staked a claim and began panning along a creek. On occasion he would write letters to his wife, but he eventually stopped writing, and after several months without any contact at all, she concluded that he had died.

That misconception might have marked the beginning of Charles Bowles’s life of grand deception—and retribution. There is much about Bowles that isn’t known, but historians have been able to put together a plausible explanation for his hatred of Wells Fargo & Company. To work his claim in Montana, he built a wooden contraption known as a “tom,” a device able to separate nuggets from rocks and sand. But, as with most forms of panning, it required a steady flow of water. His claim was promising, and eventually two men approached him and offered to buy the property. When he rejected their offer, they purchased the land above him and shut off the flow of water, making his claim worthless. Apparently these men were affiliated in some way with Wells Fargo, which had been buying substantial amounts of land around mining towns. Bowles considered their depriving him of water an act of economic war and set out to get even. One way or another, he was going to get his gold.

James Hume, after earning a decent living, also turned to the world of crime—but he took the side of the law and became a detective. In the early 1860s, he was appointed city

marshal and chief of police of Placerville, California, a gold rush settlement better known as Hangtown. At that time, little “detection” actually occurred. It was extremely difficult to connect a person to a crime through the use of evidence: It would be several decades before law enforcement appreciated the value of fingerprints, for example. And photography was a recent invention of little use to detectives. In most cases, witness testimony comprised almost all the evidence.

Under the name Black Bart, Charles Earl Bowles committed twenty-eight stagecoach robberies between 1875 and 1883—without a single person being injured.

But Hume set out to change that. He was among the very first detectives known to carefully explore crime scenes, searching for clues. He dug buckshot out of animals and walls to be used for comparisons. He analyzed footprints. He searched for connections between the smallest pieces of evidence and a suspect. In 1872, his stellar reputation earned him the job of Wells Fargo’s first chief detective. Hume was comfortably settled into his job when the bandit who would become known as Black Bart struck for the first time.

Wells Fargo had been founded in San Francisco in 1852, offering both banking and express services to miners. It used every possible means of transportation—stagecoach, railroad, Pony Express, and steamship—to carry property, mail, and money in its many forms across the West, and by 1866 its stagecoaches covered more than three thousand miles from California to Nebraska. Their famous green strongboxes, usually carried under the driver’s seat, weighed as much as 150 pounds and often held thousands of dollars’ worth of gold dust, gold bars, gold coins, checks, drafts, and currency. The long, hard, and isolated trails these coaches traveled made them desirable prey for bandits. In 1874, the Jesse James Gang committed its first stagecoach robbery, getting away with more than three thousand dollars in gold, cash, and jewels, a fortune at that time.

The legend of Black Bart began at the summit on Funk Hill on July 26, 1875, when a man stepped out from behind some rocks and ordered driver John Shine to halt. The bandit was dressed in a linen coat, had a bowler on his head, and, Shine noticed, wore rags on his feet to obscure his footprints. When the coach stopped, the robber shouted loudly to other members of his gang, “If he dares shoot give him a solid volley, boys!” Looking around, Shine saw what appeared to be the long barrels of six rifles pointing at him from behind nearby boulders. Shine didn’t argue; he tossed down the strongbox, which contained about two hundred dollars—the equivalent of about four thousand dollars today—and warned his ten passengers to stay quiet. According to the legend, one panicked woman threw her purse out the window, but rather than taking it, the bandit handed it back to her, explaining, “Madam, I do not wish to take your money. In that respect I honor only the good office of Wells Fargo.”

Black Bart sent the coach on its way. The last time Shine saw him, he was on the ground,

breaking the chest open. The driver stopped his coach at the bottom of the hill and walked back to retrieve the broken box. The robber was gone without a trace—but Shine was shocked to see that the rest of his gang hadn’t moved from their positions behind the rocks. Curious, he moved closer and discovered that the “rifles” were actually sticks that had been placed there.

With the proceeds from this robbery, Charles Bowles settled in San Francisco, where he lived under the name Charles Bolton. It was the perfect disguise: He was hiding in plain sight, enjoying the life of a city gentleman. He lived in grand hotels, dined daily at fine restaurants, and dressed to fit the role. Perfectly groomed, he carried a short cane and favored diamonds in his lapel. He was welcome among the swells of the city. When asked, he described himself as a mining engineer, a profession that required him to take frequent business trips.