Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door (45 page)

Read Bind, Torture, Kill: The Inside Story of BTK, the Serial Killer Next Door Online

Authors: Roy Wenzl,Tim Potter,L. Kelly,Hurst Laviana

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Serial murderers, #Biography, #Social Science, #Murder, #Biography & Autobiography, #Serial Murders, #Serial Murder Investigation, #True Crime, #Criminology, #Criminals & Outlaws, #Case studies, #Serial Killers, #Serial Murders - Kansas - Wichita, #Serial Murder Investigation - Kansas - Wichita, #Kansas, #Wichita, #Rader; Dennis, #Serial Murderers - Kansas - Wichita

Wichita police detective Clint Snyder holds the knife

“I have determined that for the sake of our innocent victims and their loving families and friends with us here today, for me this will be a day of celebration, not retribution. If my focus were hatred, I would stare you down and call you a demon from hell who defiles this court at the very sight of its cancerous presence…. If I were spiteful, I would remind you that it is only fitting that a twisted, narcissistic psychopath, obsessed with public attention, will soon have his world reduced to an isolated solitary existence in an eighty-square-foot cell, doomed to languish away the rest of your miserable life, alone.”

In the car, Rader lowered his head and took off his glasses with his cuffed hands. He glanced at Steed, who saw tears in Rader’s eyes.

Rader had made a lame attempt during the hearing to apologize, but no one had taken it seriously. Some of the families of his victims had not even heard it; to express their contempt they left the courtroom before he started what would become known in Wichita as “the Golden Globes speech.” Rambling on for more than twenty minutes, Rader had thanked nearly every person in the courtroom and every person he’d met in jail, as though he were taking a final bow.

He noted traits he had in common with the people he killed: military service, schooling, hobbies, pet ownership. And he spoke wistfully of his “relationship” with the cops.

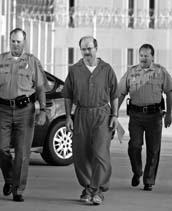

Rader’s final steps before entering El Dorado Correctional Facility to serve ten consecutive life sentences for first-degree murder.

“I felt like I did have a rapport with the law enforcement people during the confession,” he said. “I almost felt like they were my buddies. At one time I asked about LaMunyon maybe coming in and having a cup of coffee with me.”

Steed wondered: was Rader sorry, or was he sorry only for himself, that it was over, that soon he would find himself alone in a cell, while the media moved on to other stories?

Rader pointed out to Steed how green the pastures looked. Steed agreed. Kansas was usually bone-dry in August, the grass a rusty brown, but rain had brought the land to life. The world looked fresh and new.

Rader looked at the prairie, luminous at dawn. Steed realized this might be BTK’s last look at the countryside and the big Kansas sky. Rader would be housed alongside death row inmates, kept in a cell for twenty-three hours a day.

When they reached the prison entrance, Rader got out and, for a moment, did a quirky-looking stretch to adjust his back.

He shuffled to the prison door, squinting into the rising sun, surrounded by fences topped with loops of concertina wire.

He went in.

It remained for the living to ponder two questions: why did Dennis Rader do it, and why did it take thirty-one years to catch him?

The detectives who researched the records and interviewed his family and friends found no broken home in his past, no evidence of abuse in his childhood, none of the clichéd explanations for deviant behavior. The fact is, some people kill for no reason, and many people from broken or alcoholic or single-parent homes turn out well. The most disturbing thing childhood friends told the

Eagle

about Rader as a boy was that he had no use for humor. None of them knew about his inner life and the secret hobbies that he began nurturing when he was young.

Rader himself, talking frankly with the detectives during his thirty-three-hour interrogation, said there was nothing in his family or his past that made him what he was. He argued that his own explanation�that there was a demon within, a monster that controlled him, “Factor X” as he sometimes called it�was the only one that made sense. How else do you explain a man who made many friends but strangled people, who lovingly raised two children but murdered children?

Hearing this, Landwehr and his homicide detectives rolled their eyes. They know, because they talk to murderers all the time, that the character of many of them seems to be shaped by a cold-blooded egocentrism. It’s all about them; it’s always someone else’s fault; it’s always the fault of “factors”�such as how they were raised, or that they were drunk and not in their right minds when they killed the baby. Most murderers have some similar sort of jailhouse justification for refusing to accept responsibility for their acts. The cops hear these excuses from killers so much that the excuses bore them. In the end, Rader may have garnered more publicity than most killers, but to the ears of his interrogators, his justifications did not sound unique or interesting at all.

So why did he do it? Why is it that one Boy Scout grows up to become a serial killer, while other Boy Scouts like Kenny Landwehr, Kelly Otis, and Dana Gouge grow up to become the investigators who hunt him down and put him in a cage? Landwehr said it boils down to this: we all make choices. Rader made his�and ten people died.

In an interview he gave to a state-paid psychologist evaluating him immediately after his guilty plea, Rader talked about motivation: “I don’t think it was actually the person that I was after, I think it was the dream. I know that’s not really nice to say about a person, but they were basically an object…. I had more satisfaction building up to it and afterwards than I did the actual killing of the person.”

Detective Tim Relph pointed out that Rader began to plan how to lie to everyone around him long before the Otero murders. Rader made it clear that even in the air force, years before he murdered the Oteros, he was training himself to break into buildings, stalk women, and develop ruses to talk his way into their homes. When he returned to Kansas, he used his family, school, work, hobbies, volunteering, and church to create a cover story for who he really was.

There was a time when Relph thought there was a good chance that Rader was a Jekyll and Hyde, living a painful and psychologically divided life. But then Relph interviewed Rader, and it became clear to him that there was no remorse, and little division in Rader’s mind. “People will think ninety percent of him is Dennis Rader and ten percent is BTK,” he told us, “but it’s the other way around.”

Detective Clint Snyder went further: Rader is the closest thing Snyder has ever seen to a human being without a soul. “You don’t see that very often, even among murderers,” Snyder said. “Some murderers still show signs of being human and caring for others.”

Tony Ruark, one of the psychologists who was brought into the BTK case in the late 1970s, thinks that the task force detectives’ analysis is not quite satisfactory.

“Something really did happen to Rader early in life to make him the way he is. I wish I could be the one to find it,” Ruark said. “I do believe the detectives when they say that there was no child abuse in his past, no broken home, no sexual abuse. And like the detectives, I don’t think there is a ‘Factor X’ explanation, as Rader called it. There is nothing mystical about what happened to him. There is no demon within.

“Still, when I read Rader’s comments, I did not take it the way the detectives did. I don’t think Rader meant what he said to be an excuse. I’ve seen other sexually deviant people say similar things, and when they blame their behavior on a ‘Factor X,’ they are usually just trying to put a label or a name to this incredible drive they feel to perform deviant acts. I think that’s what Rader intended�to try to put a name on the drive that possessed him.”

Ruark is also certain that if Rader was honest in his answers to psychologists, “eventually we would find something that had happened to him, probably early in childhood. Now, you need to understand that whatever it was, it doesn’t necessarily have to be something big or traumatic�or even

relevant

to the rest of us. It might be an encounter or an event that the detectives and the rest of us might consider irrelevant and inconsequential, and I’m pretty sure it would be something that happened not from outside but within Rader’s own mind. But I am fairly sure we would find something, and I am sure that what we would find would be some sort of childhood event that Rader immediately associated with feelings of sexuality. Somehow, very early on, Rader encountered an event where he immediately linked sexual pleasure with watching a living creature suffer and die. And after that first encounter, Rader probably began to work very hard to nurture those feelings. He began to go out of his way as a child to create situations in which he could play out the dominance and torture to increase his sexual pleasure.”

Ruark was startled by the numerous sexually deviant fetishes Rader has, the intensity of feeling he has for them, and the incredible amount of work Rader was willing to do to satisfy them.

“I’ve treated people with sexual fetishes before, but I’ve never seen anyone like this guy, where there were so many fetishes, and where they so dominated his life: the cross-dressing, the trolling for females, the slick ad photographs he carried with him at all times, the filing system, the note taking, the enormous effort he put into burying himself while wearing a mask, and photographing himself with a remote camera.”

Ruark said he’s sure of one other thing: “These drives don’t just appear by magic. No one ever lives a normal life and then wakes up one day and decides: ‘Hey, I think I’ll go become a sexually deviant serial killer.’”

Besides the violent sexual fetishes, the dominant characteristic of Rader’s psyche is his ego. Landwehr had pondered BTK’s ego as early as 1984, when the Ghostbusters first thought to turn it against him.

Rader’s ego demands acknowledgment; he daydreams about being mysterious, like James Bond, but he craves the notoriety attached to Jack the Ripper, Son of Sam, Ted Bundy, and his other heroes.

In that June 27, 2005, interview with the psychologist immediately after detailing ten murders for Judge Waller, Rader sat in front of a camera and said, “I feel pretty good. It’s kind of like a big burden that was lifted off my shoulders. On the other hand, I feel like I’m�kind of like I’m a star right now.”

Before Landwehr and the FBI plotted out their faux news conferences in 2004, they had pondered how the news media have changed since 1974 and how those changes might prove useful. They knew that BTK did not merely crave headlines, he craved

national

headlines.

“In 1974 and in 1978, when he first wrote to us, he was still not national news, no matter how bad he was; he was still just a Wichita story,” Landwehr told us. “He saw that, so he didn’t communicate enough with us back then to trip himself up.

“But in 2004, with the Internet and cable television covering crime like they do, he finally became national news, and that played to his ego, and that really got him going. There were only five communications from BTK years ago. But there were�what?�eleven communications from BTK in eleven months in ’04 and ’05? And in the last one he made that mistake, and that’s how we finally got him.”

Some of the cops, including Landwehr, were surprised when they finally got a good look at BTK. They had assumed he would be smarter. Back in the 1970s, some cops had theorized that BTK was a criminal mastermind who disguised his intellect with crippled sentence syntax and intentional typographical errors. The timing of the “Shirley Locks” poem appeared to be connected to a contest in

Games

magazine. Local Mensa members fussed over that possible connection for years, convinced that BTK was brilliant. But it had just been a coincidence of timing.

After talking to Rader for hours at a time, the detectives concluded BTK was more lucky and stupid than smart.

And he reinforced that conclusion when he stood before the judge and the cameras on sentencing day and compared himself favorably with the people he murdered.

“Joseph Otero,” Rader said. “He was a husband, I was a husband…. Josephine�she would have been a lot like my daughter at that age. Played with her Barbie dolls. She liked to write poetry. I like to write poetry. She liked to draw. I like to draw….”

But if he is stupid, how come a police force full of smart cops took three decades to put him in cuffs?

“The Keystone Kops,” Rader called them in that post-plea talk with the psychologist. “They had thirty-some years to break it, and they couldn’t do it. The taxpayers who are paying the money for Sedgwick County, they really need to have…a sharper bunch.”

Rader wasn’t the only person who questioned the cops’ competence. There was plenty of grousing around Wichita.

By November 2005, nine months after he pointed his Glock at Rader, Scott Moon had been promoted to detective and was working in the Exploited & Missing Child Unit. He was bench-pressing weights at the downtown YMCA one day when he overheard a group of lawyers gossiping and laughing about the BTK case. Wasn’t that news conference announcing Rader’s arrest an embarrassment? All those cops just seemed to

love

patting themselves on the back. And after all, the cops didn’t do much of anything. They weren’t smart enough to catch him until the guy turned himself in. BTK was probably laughing at them.

Moon dropped his weights on the rack and walked toward the lawyers, his adrenaline pumping.