Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (11 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

I remembered that some years earlier I had read a published document about the Mulberry Street School that also paid homage to its young students: James McCune Smith’s “Sketch of the Life and Labors of Rev. Henry Highland Garnet” from 1865. Born into poverty, Smith was, in his own words, “the son of a self-emancipated bond-woman” and owed his “liberty to the Emancipation Act of the State of New York.”

4

Rumor had it that his father was a white New York merchant named Samuel Smith. The young boy was enormously talented in every subject and excelled at the Mulberry Street School. In later years, he

achieved eminence as one of the nation’s first black doctors and pharmacists and as a leading black activist as well. Initially Peter’s friend, in later years Smith became a mentor to the younger Philip White. If Peter was Philip’s father-in-law, Smith was in a sense his “godfather.”

Smith’s sketch of Garnet’s life included a list of classmates that overlapped almost exactly with Crummell’s. But each account contained omissions. To my chagrin, Smith left out Peter’s name altogether. Late in his obituary, Crummell referred in passing to Peter’s first wife, Rebecca, but used only her last name, Miss Marshall. Both writers failed to mention Rebecca’s brother, Edward, and Albro Lyons, Mary Joseph Marshall’s future husband, both of whom had been their classmate. Rebecca’s and Edward’s early deaths cannot fully explain these omissions since Smith and Crummell recalled others who died young. Perhaps one reason for their silence was their decision to pay exclusive homage to those classmates who

they

deemed “eminent” and “celebrated,” whose impact on the public history of black New Yorkers

they

assessed to be noteworthy. They were deciding whose memory was worth preserving and whose was not. They were helping to shape the archive of New York’s black community and, most significantly for me, determine the presence of my great-great-grandparents in them.

Both men relegated my great-great-grandmother Rebecca to obscurity, but Crummell at least refused to forget my great-great-grandfather. He knew that Peter had not been historically important in the way that he and many others had. But, to Crummell, Peter was worthy of commemoration because of his “character,” most notably his gift of friendship that enabled him to remain close friends with his former schoolmates until the day of his death.

I began searching for information about the school that had left such a profound mark on Peter and his friends. One of the earliest educational institutions for colored children, the Mulberry Street School was part of the African Free School system, established by the New York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and Protecting Such of Them as Have Been or May Be Liberated. As hard as I tried, I was never able to find a comprehensive black archive of the schools. All I found were some twenty brief articles published in

Freedom’s Journal

, the

country’s first black newspaper whose shortlived existence ran from 1827 to 1829. Shortly after the paper was founded, its two editors, John Russwurm and Samuel Cornish, began sending copies to the school’s library.

5

They wanted to provide good reading material for the students, but they might also have sensed that the library, housed in a white-run institution, would be better able to preserve the school’s history than their peripatetic newspaper offices. In contrast, the white philanthropists who established the African Free School system maintained a substantial written record of its activities, and Charles Andrews, the British head teacher of the Mulberry Street School for many years, published a quasi-official document,

The History of the New-York African Free Schools.

In turn, John Pintard and his friends preserved these documents in the archives of the New-York Historical Society.

The Manumission Society’s members were no radicals. Most endorsed the Gradual Emancipation Act of 1799, which rejected the call for the immediate end of slavery. They were committed to improving the lot of slaves through benevolent acts while delaying their freedom to a distant future. Indeed, many of them were themselves slave owners, unable to shake off Linnaean stereotypes about black primitiveness and inferiority, and fully aware of the degree to which the wealth of the city depended on southern and West Indian slave economies. They were quite comfortable with the existing social arrangement where they controlled the labor conditions—“ameliorated” of course—of those who worked for them.

Putting the concept of amelioration into practice, the Manumission Society established its first African Free School in 1785, limiting admission to the children of free blacks. Some four years later they agreed to admit slave children provided their masters gave permission. After the addition of a separate institute for girls, the schools were incorporated in 1794. Since public education was considered a matter of charity, these African Free Schools received limited financial aid from both the city corporation and the state legislature.

Initially, the Manumission Society hired only white teachers, and student enrollment languished. In 1797, the society changed tactics and appointed John Teasman, who would later help found the African Society

for Mutual Relief, assistant teacher, elevating him to principal two years later. As enrollment increased, the Manumission Society decided to build a schoolhouse on William Street big enough to hold about two hundred male and female students. In 1820, the boys were transferred to a new building farther north on Mulberry Street able to accommodate up to five hundred students, while the girls stayed in the William Street building.

6

On the first anniversary of the African Society for Mutual Relief’s founding, John Teasman delivered an address in which he extravagantly praised the work of the Manumission Society. “We must not forget the ingenious and heroic exploits of the standing committee of the Manumission Society in the diminution of slavery and oppression, and in the establishment of freedom and prosperity,” he intoned. “Especially we must not, we cannot forget the happy success of the trustees of the African school, in the illumination of our minds.”

7

Teasman’s praise of the officers of the Manumission Society and African Free School seems strangely at odds with the rhetoric of black pride and autonomy emanating from the African Mutual Relief Society. In fact, Teasman and his colleagues were struggling with broader questions underlying black emancipation and education. How should black New Yorkers define themselves as a community in the early decades of the nineteenth century? How should they position themselves in relation to white benefactors who expressed so much ambivalence over slavery, freedom, and the very nature of African-descended people?

On January 1, 1808, Peter Williams delivered an oration in Zion Church to celebrate the abolition of the slave trade. Henry Sipkins, William Hamilton, and other black community leaders were with him on the

podium. Families like the Marshalls, DeGrasses, and Crummells undoubtedly filled the church’s pews. Many members of New York’s white elite were present as well. Williams must have realized that his sermon required a careful negotiation between his community’s desire for autonomy on the one hand and white benefactors’ expectation of gratitude on the other. He deliberately began and ended with thankful praise of all those Europeans and Americans who had labored to abolish the slave trade.

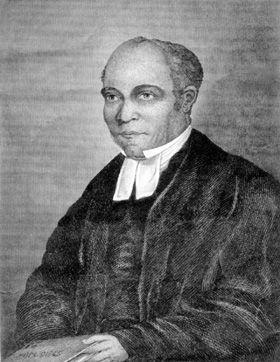

Peter Williams Jr., engraving by Patrick Reason (Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C.)

In the main part of his speech, however, Williams directly addressed the black community, retelling Africa’s recent history by casting it in the biblical language of Genesis: the African homeland had been “the garden of the world, the seat of almost paradisaical joys.” All too soon European traders arrived, however, and insinuating themselves among such innocence began practicing “all the bewitching and alluring

wiles of the seducer.” Williams then demanded that his audience bear witness to the horrors of the Middle Passage and enslavement: “Behold their dejected countenances; their streaming eyes; their fettered limbs; hear them, with piercing cries and pitiful moans deploring their wretched fates. … See them separated without regard to the ties of blood or friendship.”

8

This version of history was not based on personal memories or on ones passed down to Williams by forefathers. Rather they were invented memories that idealized the African homeland. Not everyone present had lived through such events. Yet that hardly mattered. Williams’s imagined memories resonated with all those in the audience who had suffered displacement, alienation, and oppression, uniting them into a single community. Transported into his own past, Joseph Marshall undoubtedly remembered the family and community he had left behind in Maracaibo, just as George DeGrasse struggled to remember his boyhood in Calcutta.

Beyond its nostalgia for the homeland and searing descriptions of the Middle Passage, however, Williams’s sermon offered his black auditors little to build upon. Where could New York’s black community go from here? Would African-descended people remain victims forever? Were they not capable of self-assertive action? Must they always rely on the benevolence of white philanthropists? As inhabitants of the New World, they needed useful tools for present and future action. Williams concluded by exhorting his community in the following terms. “Let us, therefore,” he proclaimed, “by a steady and upright deportment, by a strict obedience and respect to the laws of the land, form an invulnerable bulwark against the shafts of malice.”

9

Was that enough?

Some twenty years later, New York State abolished slavery and declared July 4, 1827, Emancipation Day. To commemorate the event, William Hamilton delivered an oration held once again in Zion Church. Continuing in the tradition of Teasman and Williams, he praised the Manumission Society, asserting that “it has stood, a phalanx, firm and undaunted,

amid the flames of prejudice, and the shafts of calumny.”

10

Hamilton’s rhetoric seemingly confirmed that black New Yorkers remained locked in the position of humble supplicant, bowing in gratitude before their white benefactors.

In fact, times had changed.

Black leaders had argued bitterly about how best to celebrate Emancipation Day. Many wanted orations and a parade on July 4 to emphasize the connection between black freedom and national citizenship. The Manumission Society opposed this plan, however, insisting that public demonstrations were unseemly and likely to cause violent reactions from white spectators; indeed, years earlier, it had dismissed Teasman as principal of the African Free School after he helped organize the African Society for Mutual Relief’s first anniversary parade. Most of New York’s black leadership proved willing to defer to the Manumission Society’s request. Hamilton delivered his address on July 4, but the very next day black men took to the streets, celebrating in a parade the likes of which New Yorkers had never seen.

11

Let’s follow the parade through the eyes of the mature James McCune Smith as he recalled the long-ago event in his 1865 sketch of Garnet’s life. A mere lad of fourteen, Smith stood in the crowd that day with his close friend Henry Highland Garnet, who had fled slavery in Maryland with his family and arrived in New York in 1825. Other schoolmates were there as well. I’d like to think that Peter Guignon was among them.

That was a celebration! A real, full-souled, full-voiced shouting for joy, and marching through the crowded streets, with feet jubilant to songs of freedom!

First of all, Grand Marshal of the day was

SAMUEL HARDENBURGH

, A splendid-looking black man, in cocked hat and drawn sword, mounted on a milk-white steed; then his aids on horseback, dashing up and down the line; then the orator of the day, also mounted, with a handsome scroll, appearing like a

baton

in his right hand; then in due order, splendidly dressed in scarfs of silk with gold-edgings, and with colored bands of music, and their banners appropriately

lettered and painted, followed, “The

NEW YORK AFRI-CAN SOCIETY FOR MUTUAL RELIEF

,” “The

WILBERFORCE BENEVOLENT SOCIETY

,” and “The

CLARKSON BENEVOLENT SOCIETY

”; then the people five or six abreast, from grown men to small boys. The side-walks were crowded with the wives, daughters, sisters, and mothers of the celebrants, representing every State in the Union, and not a few with gay bandanna handkerchiefs, betraying their West Indian birth: neither was Africa itself unrepresented, hundreds who had survived the middle passage, and a youth in slavery joined in the joyful procession.

As he remembered that momentous day, Smith reverted to his youthful self to relive the thrill of the occasion. Yet even in the midst of his exuberance, Smith took pains to underscore its political significance: the military prowess of the uniformed marchers, the efficacy of black community organization, and the importance of black solidarity, in essence an early version of “black power and black pride.” To reinforce his message, Smith reminded his readers that commemorations of the past like the Emancipation Day could and should be an inspiration to black youth to look to the future and “march on”: