Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (6 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

The fourth circle was that which lay beyond the “city and vicinity.” The black elite interacted with relatives, friends, and fellow activists in other cities—Philadelphia, Boston, Rochester, for example. But in addition, frustrated by the racism that pervaded the city of their birth, many chose to go into self-imposed exile—to other cities, to upstate New York, or across the Atlantic to England or the African continent.

Yet with few exceptions these men and women returned to New York, almost as if the city held them in thrall. It was, I think, the chance of beating the odds, the intellectual ferment, the social activism, and the political energy of the city that brought them home.

The last circle was the cosmos itself. As they struggled to define what it meant to be a black American, members of the elite rejected any narrow and parochial definition of themselves. I was astonished to discover that one hundred years before my father and my aunt, many among them had acquired a cosmopolitan sensibility. Reading, study, work, and travel abroad gave them an opening onto a new world of culture, taste, and aesthetic appreciation that extended far beyond their racial group, their city, and even their nation. The more they read and traveled, the more determined they were to expand their identity beyond that of “colored American” to include “citizen of the world.”

Over the course of my narrative I deepen my lens as more archival material about my great-grandfather’s life became available to me from the 1850s on. As a consequence, Philip White emerges as the hero of my book. Nevertheless, I’ve been frustrated in my efforts to gain access to what Morrison called “the unwritten interior lives” of nineteenth-century black Americans. My most intimate glimpses of my great-great-grandfather and great-grandfather have come ironically enough from their scrapbook page memorials. I learned to read between lines and between items. I came to realize that four of the poems placed to the left of Philip White’s obituary were in fact indirect commentaries on what my great-grandfather had cared about so passionately in life. “Why Johnny Failed, Good for a Boy to Learn” speaks of the difficulty of educating black children. “To Trinity” is a paean to the mother church that gave birth to St. Philip’s. “References” pays homage to a dead man whose life had centered not so much on public affairs as on the “little home … and wife and children three.” And “If We Only Understood” is a mysterious plea not to judge a person’s external appearances “knowing not life’s hidden forces.” The scrapbook page, I realized, memorializes both a public and private life.

I’ve written

Black Gotham

out of a sense of obligation to the dead, to give a face to those left faceless by acts of trauma and erasure. I also feel I owe something to my family and my community—not only black

Americans but Americans nationwide. In writing a new and different version of African American history that challenges the ones we’re so used to reading, I’m hoping to find a usable past for a nation that 150 years after emancipation still has a long way to go in solving its racial problems.

Black Gotham

is meant to be an act of reparation, an act to repair the tears of memory—tears in the sense of both sorrow and rupture.

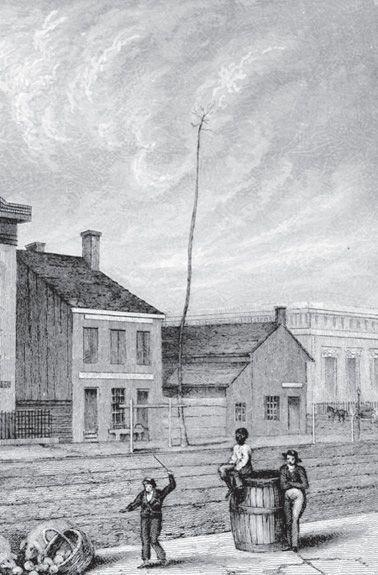

Lower Manhattan

1795–1865

Collect Street

CIRCA 1819

WHERE TO START? I STARED

at the two obituaries and settled on that of the older man, my great-great-grandfather Peter Guignon, hoping to find information about

his

parents. But Alexander Crummell’s references to his friend’s background were circumspect. “Peter’s mother,” he wrote guardedly, “was a native of the West Indies and came thence to the city of New York and resided there until her death.” The sentence raised more questions than it answered. What part of the West Indies did Peter’s mother come from? Who was his father and what was his racial identity? Further information came to me in stages and to this day remains woefully incomplete. I uncovered a brief notice of Peter’s death in the

Brooklyn Eagle.

The deceased, it noted, “was born in Bayard Street in 1814, his parents having come from Hayti.”

1

Although I now knew Peter’s parents’ place of origin, the obituary prompted even more questions. Why and how had they come from Haiti? Were they living together on Bayard Street? Were they the household listed in the 1820 census as composed of the free white James Guignon residing in the Sixth Ward with a free white woman and male child under ten? But Peter was not white, so his mother couldn’t have been either. Was James Guignon living with a light-skinned black woman? Were they married? Was he passing her and their son off as white? Why did Crummell make no mention of him?

Peter Guignon

A chance introduction to a historian at a conference led to a discussion of my dilemma. To my astonishment, some months later I

opened my email to find that she had sent me copies of records she had happened upon in the archives of St. Peter’s Church in Lower Manhattan. The most significant document was a bann of marriage dated February 1811, which read in part:

Alexis Duchesne has been born at Laon in champain, & Sophie Guignon Was born in the Ile of St Domingue. This marriage was celebrated after Three Successive publications of the bans. Witnesses have been the Following, who have signed their names, Viz: Jean Baptist Gunian, Joseph Pierre Bérard, Pierre Guignon, Jacques Guignon Et autres.

2

The bann placed the Guignon clan in the same social circle as the Bérards, who are well known in the historical record as

grand blanc

slaveholders forced to flee Saint-Domingue at the time of the revolution. The Bérard family arrived in New York in the late 1790s with their slaves but without the great fortune they had amassed.

3

I don’t

know who Sophie Guignon was or which Guignon might have fathered Peter—Pierre, Jacques (the French name for James), or yet another. But this man was clearly the “white Haitian” that my family had referred to so vaguely when I was a child. Peter’s mother was undoubtedly a mulatto woman who had come with the Guignons from Haiti, as a slave, a servant, or perhaps a free woman. The deafening silence around their relationship and the father’s absence from Peter’s life suggested to me that they were not married.

Having reached a dead end, I decided to shift tactics and approach Peter through his in-laws, who I knew from Williamson’s genealogical notes were named Elizabeth Hewlett Marshall and Joseph Marshall. They are the starting point of my story, shadowy figures in the background urging me forward to compose a picture in black and white of early social life in New York City.

Armed with a new family name, I went to the municipal archives and plowed through city directories, tax assessment records, and minutes of the Common Council. Here’s what I found.

In 1818, the City of New York sold at auction land on Lower Manhattan’s Collect Street to one George Lorillard, a wealthy tobacco merchant and real estate speculator. Among the lots purchased were numbers 17, 18, and 19, also 39 and 40, 51 and 52, and 80 through 83. Lorillard promptly turned the properties around and leased or sold several to a group of black New Yorkers. In 1819, the African Episcopal Society—soon renamed St. Philip’s Episcopal Church—acquired a sixty-year lease on numbers 17, 18, and 19. That same year, George DeGrasse became the owner of lots 79 and 80. In 1820, Boston Crummell acquired lot 51, and Joseph Marshall lot 40. After a house was built on his lot, Marshall’s property was valued at $900. When Collect Street was renamed Centre Street, Marshall’s house was renumbered 72. In 1829, its value was listed at $1,200. After his death, the property passed to his widow, Elizabeth Hewlett Marshall, who built a rear house on the premises. By 1838, the total value of the property had risen to $2,000.

4

Who were the parties to these real estate transactions? Let’s begin with the black families, the DeGrasses, Crummells, and Marshalls. What were their backgrounds? How were they able to become property owners—or freeholders—in early-nineteenth-century New York? Much earlier, under Dutch rule, the director general of New Netherlands had given farmland north of the city to some thirty Africans in order to create a buffer protecting the Dutch from attacks by Native Americans. But after the slave insurrection of 1712, the New York Assembly passed “An Act for preventing suppressing and punishing the Conspiracy and Insurrection of Negroes and other Slaves.” Among other things, this act prohibited blacks from owning property. Not until 1809 would they once again be allowed to inherit or bequeath property.

5

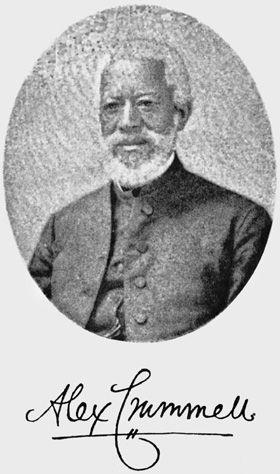

I searched for the names of the three men in African American history books and found some information on both Crummell and DeGrasse. Boston was Alexander Crummell’s father. An amazingly prolific writer, Peter’s childhood friend has left us with many letters, essays, speeches, and sermons, some published in collected volumes during his lifetime, others still stored in manuscript form in the Schomburg Center archives. Alexander maintained that his father was born in Africa “in the Kingdom of Timanee” (now Sierra Leone); some even claimed that Boston was descended from Temne chiefs. It was Alexander’s belief that his father “was stolen thence at about 12 or 13 years,” arriving in the United States around 1780. Boston eventually became the slave of Peter Schermerhorn, a member of an old and prominent Dutch family, who had increased the family’s wealth through the shipping industry and speculation in Manhattan real estate. Legend has it that Boston “was never emancipated,” but simply told Schermerhorn one day that “he would serve him no longer” and “notwithstanding all remonstrations and intimidations could not be got back.” Proud of his father’s act of resistance, Alexander frequently referred to himself as “the boy whose father could not be a slave.”

Boston married Charity Hicks, a free woman from Long Island, who was reported to have been brought up in “the same family that produced the celebrated Quaker, Elias Hicks.” Hence, his “

maternal

ancestors,” Alexander asserted, “have trod American soil, and therefore have used the English language well nigh as long as any descendants of

Alexander Crummell, abolitionist, Episcopal minister, and missionary, circa 1890s (Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library)

the early settlers of the Empire State.” In freedom, Boston took up the trade of oysterman and became a highly respected member of the black community. Yet he never forgot his place of birth. Etched in Alexander’s mind were Boston’s “burning love of home, his vivid remembrances of scenes and travels with his [own] father into the interior, and his wide acquaintance with divers tribes and customs.” In later years, Boston hoped to return to Africa and establish a farm in Liberia, but died before

doing so. It was left to his son to make that journey with his wife and children in the 1850s.

6