Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (5 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

At the Schomburg, I found an even more valuable cache, the Harry Albro Williamson Papers, preserved on a number of microfilm reels, which I’d been told was one of the few nineteenth-century family collections held at the center. I had no idea who Williamson was or who his family might be, but I started systematically working my way through his papers. Born in New York in 1875, Williamson seems to have dedicated his entire life to freemasonry, amassing volumes of material to compile a comprehensive history of black lodges in the United States. But Williamson was also interested in family history, and in plowing through his genealogical notes I made a serendipitous discovery just as astonishing as the earlier obituaries. Neatly typed on a piece of paper was the following line: “Rebecca was married to Peter Guignon in 1840; she was his first wife.” When least expected, I had found one more

link to my family! Rebecca was none other than the Miss Marshall who Alexander Crummell had named in the obituary of his old friend. Her parents were Joseph and Elizabeth Marshall. The Marshalls had an older daughter, Mary Joseph, who married Albro Lyons, also in 1840. One of the Lyons’s daughters married William Edward Williamson, and Harry was their son. If you’re still with me, Harry Albro Williamson is my grand-uncle.

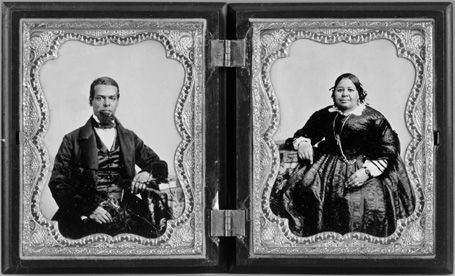

Double ambrotype portrait of Albro Lyons Sr. and Mary Joseph Lyons, circa 1860, by an anonymous photographer (Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library)

It was clear to me that Williamson was determined to preserve as much of his family history as possible. He compiled genealogical lists. He jotted family stories he had heard down on paper, beginning with comments like “I often listened to the story of how” or “I can recall my grandfather telling me.” He put together a nine-page typed document titled “Folks in Old New York and Brooklyn” in which he explicitly warned of the dangers of historical forgetting: “The various items which shall follow are intended for the present generation (1953) of citizens of color who have little or no knowledge pertaining to members of

their race whose identities have now completely disappeared from local records because the old have been replaced by the new.”

11

In Williamson’s papers I uncovered an even more telling example of the will to record the history of nineteenth-century black New Yorkers in a memoir written by another daughter of Albro and Mary Joseph Lyons, Maritcha Lyons (Williamson’s aunt and hence my great-grand-aunt). Born in 1848, Maritcha composed her memoir for publication in the late 1920s but died before completing a final draft. In reading through it, I was amazed at how deep the commitment to preserve family and community history ran in the Lyons family. In her introduction Maritcha noted that her father had hoped to write a book about his life and times but never got further than the title, “The Gentlemen in Black.” Given that he had been one of Peter Guignon’s schoolmates at the old Mulberry Street School and later his brother-in-law, I can only lament that Lyons was never able to fulfill his writerly aspirations. Lyons asked his daughter to carry on his legacy. Although Maritcha was convinced that her “literary nephew” was better suited to the task, she dutifully complied, working from “the vast output of fugitive scraps” that Williamson had gathered over the years. The very title of her memoir, “Memories of Yesterdays, All of Which I Saw and Part of Which I Was—An Autobiography,” suggests just how eager she was to preserve the memories of her father’s generation.

12

Now it’s up to me.

Had my grandparents, Cornelia White and Jerome Bowers Peterson, tried to emulate the example of their contemporary, Harry Albro Williamson? I’ll never know.

“Colored men! Save this extract. Cut it out and put it in your Scrapbook, and use it at a proper time.” So reads the caption of an article titled “Black Heroes” published in the March 10, 1854, issue of

Frederick Douglass’ Paper

, the major black newspaper of the mid-nineteenth century. In writing these lines the author was exhorting his readers to save his article in a scrapbook as a way of keeping alive for possible future action memories of black soldiers who had bravely fought on the side of

the Republic during the revolutionary war. The lines reminded me of the scrapbook pages in the Rhoda Freeman collection on which an anonymous owner had pasted Peter Guignon’s and Philip White’s obituaries as a memorial to these two men. It made me wonder whether even the small, personal act of keeping a scrapbook could also be a form of public history making.

Scrapbooking is a household art with a long, time-honored tradition, popular to this day. Scrapbooks memorialize, preserving in physical form significant experiences the owner wishes to remember, savor, and maybe even leave as a testament to loved ones. What gets put in scrapbooks varies tremendously from owner to owner: flowers, locks of hair, ticket stubs, postcards, handwritten notes, clippings from newspapers or other publications. Items may range from public issues to community affairs to family and personal matters. In pasting these items in their scrapbooks, owners create their own versions of history, composing new narratives out of old recycled material. And since scrapbooks are not meant for publication, owners are not obliged to follow any particular set of rules but are free to create as they please.

Thus, scrapbooks run the gamut from private musings to forms of history making that address a public need. For nineteenth-century black Americans, scrapbooks became a way to write their history, one in which they were the central protagonists, not the marginalized, despised, or forgotten. Telling their history from their own perspective, they allowed multiple voices—sometimes in harmony, sometimes in tension with one another—to emerge. Whatever their content, their scrapbooks, much like archives, reflected a sense of the evanescence of experience, a fear of forgetting, and a determination to preserve past events for posterity.

Williamson’s family collection is a scrapbook of sorts. It’s filled with cards, letters, genealogical charts, newspaper clippings, and recollections from him and others written down by hand or in typescript—what Maritcha tellingly referred to as the “fugitive scraps” from which she composed her memoir. Following in their footsteps, I imagine this book as a kind of scrapbook that memorializes my nineteenth-century forebears, their friends, and acquaintances. I haven’t been able to account

for all facets of their lives, so my narrative is made up of what I found and what I didn’t find in the archives, of what was remembered and what was forgotten.

Like Morrison’s Denver, I’ve tried to endow the few scraps of memories I possess with blood and a heartbeat. But, unlike Denver, my memories are not those of a still living parent and grandparent but of distant ancestors who have bequeathed to me even less than Sethe and Baby Suggs gave her. This absence of memory has weighed heavily on me.

Reflecting on her method for writing

Beloved

, Toni Morrison explained how “I must trust my own recollections. I must also depend on the recollections of others. Thus memory weighs heavily in what I write, in how I begin and in what I find to be significant. … But memories and recollections won’t give me total access to the unwritten interior life of these people. Only the act of the imagination can help me.”

13

I’m not a novelist, however, and I can’t compensate for my family’s silences by writing fiction. Instead, I’ve turned to the archives. On a personal level, my research in the archives has been a form of memory work for me. Professionally, I’ve operated like a historian, working to make sense of the scraps I’ve found, selected, and brought together. I uncovered few personal documents that could give me insight into the feelings, psychological states of mind, or motivations of family members. Instead, I found information primarily in public documents: black newspapers such as New York’s early

Freedom’s Journal

and

Colored American;

Frederick Douglass’s

North Star

and

Frederick Douglass’ Paper;

the shortlived

Weekly Anglo-African;

and the postwar

New York Globe

(later the

Freeman

and

Age

), as well as white ones, notably Horace Greeley’s

New York Daily Tribune

and the

Brooklyn Daily Eagle;

records of meetings of the Philomathean Society, the Brooklyn Literary Union, and other organizations; proceedings of black conventions such as the state convention held in Albany in 1840; and acts of incorporation like that of the New York Society for the Promotion of Education Among Colored Children.

Putting these scraps together, I’m hoping to fulfill my family’s legacy and write the history of the “gentlemen in black.”

This book is a partial history: partial because it tells only one part of nineteenth-century New York history; because it favors family history as a point of departure; because it is made up of fragmentary parts; because I am part of it as descendant, researcher, and narrator; because I have allowed my quest to find lost family memories to become part of my story.

Each chapter title contains a date, a place, or an event of some importance to my great-great-grandfather, my great-grandfather, or one of their close associates. Similar to a clipping or a snapshot, that is the scrap I’ve chosen to paste in my scrapbook. I then let the work of memory, history, and archival discovery guide me through my narrative.

Bit by bit, I widen my lens. I see Peter Guignon and Philip White as living within several circles, each wider than the last. The first was what Crummell called “the wide circle of the leading citizens of New York and vicinity.” Bound together by more than family ties, Guignon and White were part of a small class of educated blacks; pharmacists by profession, they were comparatively wealthy; they worshiped together at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, often joined the same organizations, and fought for the same political causes; they turned to the same group of friends, many of them Guignon’s former schoolmates, for succor and counsel. Taken together, these men, their wives, and their children constituted New York’s black elite, a social circle so tightly knit that they could almost think of themselves as a “family.” I have to confess that I see Guignon as an unremarkable member of this group. In contrast, Philip White’s individual achievements were quite amazing; he qualifies as “the first” in so many of his endeavors. Yet he could not have accomplished what he did without the help of Guignon’s former classmates, Patrick and Charles Reason, James McCune Smith, George Downing, Alexander Crummell. In his youth, they were his mentors. As he grew older, they became his intimate friends just as they were his father-in-law’s.

The second circle was the black community. New York City’s African American population was never very large. In 1810, it numbered 7,470 free persons and 1,446 slaves out of a total population of 91,660. In

1830, the city’s slave population had dwindled to 17 while the number of free blacks stood at 13,976 out of approximately 202,600 inhabitants. In 1840, the black population peaked at 16,358 (out of 312,700), and then it slowly declined to 12,574 (out of 813,700) in 1860.

14

In Brooklyn the numbers were even smaller: in 1860, there were 4,900 blacks out of a total of 266,000 inhabitants. They lived, as social historians like to say, in the black community that cohered around a number of institutions: the African Society for Mutual Relief; the Mulberry Street School; churches like St. Philip’s or Mother Zion; newspapers like

Freedom’s Journal

, the

Colored American

, the

New York Globe, Freeman

, and

Age;

and the annual conventions of colored people.

Neither Peter, Philip, nor their friends remained confined to the black community, however. They inhabited a third circle, the city itself as well as its “vicinity” (Brooklyn). In a time before residential segregation hardened, they and other black New Yorkers lived and worked in racially mixed neighborhoods next to people of differing ethnicities and, at least in the early years, of different classes. In these neighborhoods, blacks interacted on a daily basis with whites of all classes—poor Irish and German immigrants as well as upper-class whites. Despite their differences, they were all subjected to the same indignities of metropolitan life: filth, epidemics, disease. Beyond the geographical confines of their neighborhoods, Peter, Philip, and others who worked in trades or professions had a wide variety of contacts with whites throughout the city—as colleagues, employers, or customers. As political reformers, they worked alongside white activists. During their leisure hours, they mingled with whites in public venues like the Crystal Palace. My most fascinating discovery was that of the Lorillard family—tobacco merchants, tanners, city officials, cultural power brokers—whose lives intersected with those of my family over several generations in surprising ways.