Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (7 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

George DeGrasse’s background could not have been more different. Neither African nor European, he was a Hindu, born in Calcutta, and reputed to be the foster son of Admiral Count de Grasse, the commander of the French fleet that had helped George Washington triumph over the British at Yorktown in 1781. Before that, Count de Grasse had served in the French navy in the Mediterranean and India where he likely adopted George. He died in France in 1788, leaving his son in the United States.

In 1802, Vice President Aaron Burr, who had undoubtedly become acquainted with the older De Grasse during the revolutionary war, wrote a letter to his daughter Theodosia in which he referred to “my man George (late Azar Le Guen, now George d’Grasse).” Two years later, George DeGrasse petitioned the Court of Common Pleas to become a U.S. citizen. The court agreed that he had resided in the United States for a period of five years and in New York state for one. So upon showing proof of good moral character, swearing to uphold the Constitution of the United States, and promising to renounce allegiance to all foreign states, “the said George DeGrasse was thereupon, pursuant to the laws of the United States in such case made and provided, admitted by the said Court to be, and he is accordingly to be, considered a citizen of the United States.” Had George DeGrasse been a black born in Africa, he undoubtedly would not have received U.S. citizenship.

7

A naturalized Hindu American, DeGrasse chose to cast his lot with New York’s black community when he married Maria Van Surlay. Maria’s racial background was even more complicated than that of her husband. It’s believed that sometime in the early seventeenth century a Dutchman by the name of Jan Jansen Van Haarlem entered the service of the sultan of Morocco and married a local woman. One of their sons, Abram Jansen Van Salee, settled in Brooklyn, where the phrase “alias the mulatto” or “alias the Turk” was regularly appended to his name. Maria was born some eight generations later. One of her and George DeGrasse’s children, John, became a doctor and moved to Boston; another, Isaiah, was a Mulberry Street School classmate of Peter Guignon and Alexander Crummell. According to his contemporaries, Isaiah was

so light skinned it was impossible to distinguish any trace of African ancestry in him.

8

But I had no luck finding Joseph and Elizabeth Marshall in any published history books. My single source of information about my great-great-great-grandparents has been Maritcha Lyons’s memoir. Her comments about her grandparents are fascinating and tantalizing, but ultimately frustrating. Maritcha duly recorded that Joseph was a house painter who had been able to scrape enough money together to build a house for his family on Collect Street, and that “after his decease grandmother erected a rear house and converted the basement of the front dwelling into a store in which she opened a bakery.” This fact is preceded, however, with an explanation of her grandparents’ background that raises more questions than it answers:

My maternal grandmother, Elizabeth (Hewlett) Marshall, was distinctly a poor white of English descent. Her mother’s name was King and that of her mother’s mother, was Bartlett, good old English appellations. She had one brother, James Hewlett, a “play actor” as stage performers were derisively styled in bygone days. She and her sister Mary, in common with girls of their station, were apprenticed. … [She united] her fortunes with those of my grandfather, Joseph Marshall, a native of Maracaibo, Venezuela. His family, after the continental fashion, had planned for him to enter the Roman priesthood. This was so contrary to his desire that he hastily and secretly left home.

9

What did Maritcha mean when she referred to Grandmother Marshall as a “poor white of English descent”? When she used the term “white,” was she speaking of skin tone? Surely she was not suggesting that Elizabeth was racially white. The reference to Elizabeth’s kinship with James Hewlett lets us know that, however light skinned, she was not white. A member of the African Grove Theater Company as well as a solo performer in the 1820s, and a fairly disreputable character with a criminal record in the 1830s, James Hewlett was much in the public eye. His place of birth was a subject of open debate. James McCune

Smith suggested that he came from the West Indies, trying perhaps to protect the family’s reputation. Yet it was a pretty well known fact that Hewlett was “a native of our own dear Island of Nassau [Long Island], and Rockaway is said to have been the place of his birth.” And there was certainly no question about his race. He was regularly referred to in the press as “African,” “colored,” “black,” and even “darky.”

10

In her account, Maritcha proudly emphasized her grandmother’s English ancestry by noting the maternal surnames of King and Bartlett, but made no reference to Elizabeth’s father. So was it Elizabeth’s mother who was “a poor white,” and did she marry a black man? I don’t know. But if Rockaway was indeed their place of birth, I’m surmising that, just as Charity Crummell was related to the Quaker Hickses, Elizabeth and James Hewlett were members of the Hewlett family whose ancestor George had emigrated from England to America in the mid-seventeenth century. By 1658, George Hewlett had become a prominent landowner, and eventually the family gave its name to a town on Long Island.

And what about Elizabeth’s husband, Joseph Marshall, a native of the port city of Maracaibo, Venezuela? In 1801 Maracaibo had a population of approximately twenty-two thousand, divided among Spanish nobility, white planters, slaves, and freedmen, mixed bloods referred to as people of color. I’m guessing that Marshall was of Spanish and African ancestry and came from this latter class, anglicizing his name upon his arrival in the United States. In the Venezuelan Spanish colony, missionary activity was as important as military conquest, administrative control, and economic exploration. Free people of color were disbarred from holding public office and restricted in the trades and professions they could practice, but they were welcomed into the priesthood. Perhaps it was that fact rather than any “continental fashion” that led to Joseph’s family’s plan to have him enter the clergy.

11

These brief sketches suggest just how complicated the racial and ethnic origins of the men and women on Collect Street were. They claimed diverse national backgrounds, were of different racial mixtures, and had complexions ranging from ebony to ivory. I’m left wondering what made them, in the language of the day, “African.”

Their histories differed dramatically. Some were born in the United

States, others in Africa, India, or South America; their ancestors came from places as diverse as England, the Netherlands, Spain, Morocco, and Sierra Leone. Only Boston Crummell was pure African. The rest were Creoles, mixtures of different races. Most seemed to possess visible racial characteristics of skin color, hair, and facial features, although Elizabeth Marshall appeared white. Such complications were less of a problem in the colonial era when racial mixing was more tolerated and race itself not clearly defined. But by the late eighteenth century, racial classification schemes were rapidly spreading throughout Europe and America. The Swedish natural historian Carl Linnaeus, for example, created a hierarchy of

homo sapiens

, placing the African on the last rung below the European and the Asiatic and just above

homo monstrosus.

Linnaeus defined the African’s external traits as

black skin, frizzled hair, flat nose

, and

tumid lips.

Mixed-raced persons were increasingly deemed African if they exhibited any of these features, even if attenuated, or if it could be proved that they had African ancestry. To the external characteristics of the African corresponded the internal, devalued traits of

crafty, indolent, negligent

, and

governed by caprice

that rendered him unfit for citizenship.

12

Ethnically and racially diverse as they were and well aware of the degraded status that accompanied the term “African,” the men and women of Collect Street nevertheless chose to band together, create a tight-knit community, and forge an identity and place for themselves as Africans in America. Yet they remained alive to the “elsewhere,” the many places across the globe from which their forebears originally hailed. Long before my father and my aunt, they acquired a cosmopolitan sensibility that shaped their outlook in at least two important ways. Engrained in them was a profound appreciation of and respect for cultural difference. They understood that although cultures might vary, this did not mean that one was necessarily superior to the other. They also intuited that individuals like themselves could forge deep affiliations with more than one culture and hold overlapping allegiances that did not contradict one another. These understandings led them to the unswerving conviction that beyond cultural difference lay the universal, ethical value of

character

that all human beings needed to cultivate.

So what was Africa to them? For most of these men and women,

the continent was an unknown or at best distant past. Yet on a gut emotional level, its history resonated deeply. It became a metaphor for the experiences of displacement, exile, alienation, suffering, and perhaps future redemption that they and their ancestors had suffered across time and place. More pragmatically, Africa functioned as a strategy. It became a rallying cry through which to gain strength in numbers and engage in effective political and social activism. As a result, they embraced the label “African” as a common heritage and identity. In speeches idealizing the motherland, celebratory street parades, burial practices, and the like, this early “African” community made the continent a source of imagined memories and laid the groundwork for collective action.

In his Collect Street land transactions, George Lorillard offered a sixty-year lease on a plot of land to the African Episcopal Society, one of New York’s first black community institutions and my family’s place of worship. The DeGrasses and Crummells were among its first parishioners and might well have been responsible for its location close to their homes on Collect Street. In the Marshall family, Elizabeth was a Baptist and Joseph a member of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. But their children shifted their religious affiliation to the Episcopal denomination, and by 1840, if not earlier, both the Guignon and Lyons families were members of St. Philip’s. The church’s history is the uplifting story of black New Yorkers’ quest to fulfill their religious needs. But it is also the more hardscrabble story of the tremendous material hardships they faced.

Many black New Yorkers chose to become Episcopalians because Anglicanism, represented by Trinity Church, dominated the city’s early religious life and was the first denomination to reach out to them. Under the auspices of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, Frenchman Elias Neau began instructing slaves in Christianity around 1705. After his death in 1722, a succession of assistant ministers at Trinity continued his work.

The upstanding members of Trinity Church wanted their black

slaves and servants to be good Christians. But they did not want them praying next to them, receiving religious instruction with them, or buried alongside them. So Trinity’s black parishioners set their sights on establishing a church of their own with three specific goals in mind: establishing a place dedicated to worship, to the religious instruction of their community, and to the burial of their dead.

13

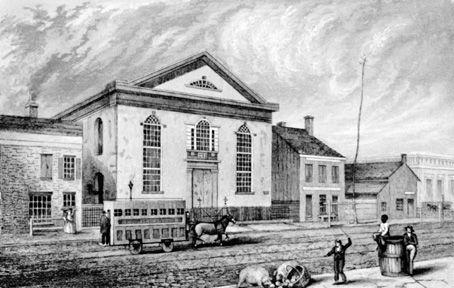

St. Philip’s Church, Centre Street, circa 1819 (New-York Historical Society)

The Trinity Church vestry minutes provide a detailed chronological narrative. As early as 1792, black parishioners petitioned Trinity for a lot of land on which to build a schoolhouse. After the destruction of the city’s black cemetery, the Negroes Burial Ground, in 1795, a group of black men requested financial aid “to purchase a piece of ground as a burial place to bury black persons of every denomination and description whatever in this city whether bond or free.” The city set aside two lots of land on Chrystie Street for this purpose. Trinity contributed toward the expense and also agreed to the formation of an African Catechetical Institution for religious instruction. But the institution had no fixed location and over the years was forced to move from room to room in different buildings.

Black parishioners repeatedly begged Trinity for a permanent

home. By 1817 the African Catechetical Institution’s Board of Managers became so exasperated with Trinity’s foot-dragging that they fired off an angry letter. Signed by Peter Williams, who would later become St. Philip’s first pastor, it threatened a mass exodus from the denomination. Black Episcopalians, Williams wrote, held out hope of

providing a convenient place, of securing to the Church the attachment of a large number of coloured persons. On the other hand, it is most evident that if some such arrangement is not soon made there will be a great falling off in that class of Episcopalians. Your petitioners have to lament that, within the compass of their knowledge, some hundreds have already left the church, whom they have reason to believe would not have done so had some such provision been made for their accommodation. And as heads of families they feel the more anxious for it to be made, lest their children should also be led to depart from that form of worship, and those doctrines which they believe to be most scriptural and most conducive to the interests of true religion.