Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (28 page)

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

Philip entered his store and surveyed it with satisfaction. Like most drugstores of the day, it was well stocked with toilet articles and perfumery, to which he was slowly adding hardware items such as window glass, paints, oils, and mirrors. He also sold liquor, fully aware that although many of his customers claimed that they were buying it for medicinal purposes, they would undoubtedly drink it instead.

Philip’s main task, however, was dispensing drugs to the sick. Just as in his apprenticeship days, he spent long hours at his prescription counter, since, like most pharmacists, he prepared almost half of his prescriptions right on the premises. Philip’s cabinet was made of cut glass, and it held everything needed to fill a prescription. He stored his Shaker herbs in tin canisters neatly stacked one on top of the other, and poured various extracts, tinctures, waters, acids, and syrups into bottles lined up in neat rows. All the containers were carefully labeled. Tools such as scales, spatulas, labels, and corks lay close at hand next to the ever indispensable Dispensatory. Complete with a coal stove and gas or alcohol lamp for heat, a mortar and pestle or drug mill for grinding, Philip’s prescription counter was a true laboratory where he could compound almost any drug on the spot.

52

Philip set to work filling a prescription for his good friends Albro Lyons and William Powell, who were joint owners of the Colored Sailors’ Home at 330 Pearl Street near the East River. They had sent word that several of their sailors were suffering from diarrhea and vomiting, and were worried that these symptoms portended a new outbreak of cholera. Philip thought it unlikely since there had been no recent reports of the disease. He thought back in horror to the 1849 epidemic, which had started in an immigrant boardinghouse on Orange Street and then spread rapidly through the Five Points to the rest of the

city. The epidemic had been shortlived but intense: 5,017 dead in four months. Thankfully, health officials were now pretty much convinced that the disease was not a moral failing but a result of social and environmental conditions. And to their credit, health practitioners were now devising less drastic treatments. They no longer indulged in excessive bleeding and purging. And although they still recommended calomel taken in combination with either laudanum or opium pills to stem the diarrhea, and camphor to relieve cramping, they now prescribed them in lower doses.

53

Philip prepared his prescription with great care.

Having finished, Philip headed downtown toward Pearl Street to deliver the prescription, wending his way through one of the city’s most commercial districts. Shipbuilding industries dominated the East River waterfront area. This was where shipping magnates like John Jacob Astor, Archibald Gracie, William Aspinwall, Robert Minturn, and others had made their fortunes, trading in goods of all kinds, including slave products, across the world. Longshoremen swarmed the port. Most of them were Irish, and Philip knew how determined they were to keep black workers off the docks. The area also housed trades associated with shipping, reputable ones like boardinghouses and outfitting stores for sailors, and less reputable ones like grog shops and brothels.

54

William Powell had fared well, opening his Sailors’ Home in the late 1830s. But he was now thinking of moving his family to England and had arranged for Albro Lyons, who owned two Seamen’s General Outfitting Stores on nearby Baxter and Roosevelt Streets, to take over the business.

The Colored Sailors’ Home was a landmark in the black community. In the very same newspaper article in which he had mentioned Philip’s newly opened drugstore, William Nell had heaped praise on Powell’s home. “An Oasis in the desert,” he called it, where “the Banner of Reform floats conspicuous.” The home enforced temperance and encouraged reading; at mealtime the conversation dwelled “on the various questions incidental to the elevation of man.”

55

Philip fully agreed with Powell’s philosophy that it was the responsibility of the more fortunate in the community to elevate the less fortunate. After having determined that the ill sailors were only suffering from a mild case of dysentery,

Philip left, promising to return with books for the home’s already substantial library.

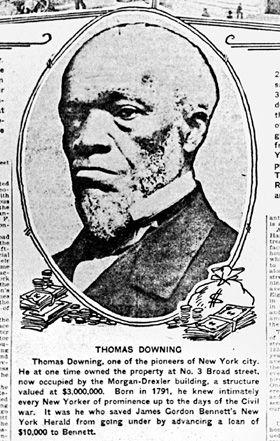

Thomas Downing, New York City, pioneer and restaurant owner, circa 1860s (Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library)

Now hungry, Philip decided to splurge by dropping in at Thomas Downing’s oyster house on Broad Street. Philip always entered Downing’s establishment with a sense of amazement that the son of freed Virginia slaves had done so well in the competitive world of New York’s eating houses. Downing knew his oysters as well as Ray did his tobacco. When the oyster trade was still new, Downing would get up at two in

the morning to row over to the Jersey Flats and gather the oysters himself. Now he left that work to others. But with competition as stiff as it was, he still went out at midnight to wait for the oyster boats, or even to sail out to them, so he could beat the competition and get the best catch.

56

Downing’s restaurant was simply furnished and lacked the adornment of other oyster houses, but that hardly mattered. Because of its proximity to the Customs House, the port, the merchant exchange, banks, and other important businesses, Downing counted some of New York’s most powerful men among his customers: Samuel Swartwort, collector of the port; William Price, district attorney; Jonathan Coddington, postmaster; Abraham Lawrence, president of the Harlem Railroad, to name just a few. Philip had often watched as Downing passed messages back and forth from customers at one table to another. Because of all this message carrying, people assumed that Downing wielded influence at the highest level of city government; as a result, scores of office seekers flocked to his establishment.

57

Whether the rumor was true or not, it had the effect of bringing in more customers.

But Philip also knew the difficulties Downing, like so many other black men in the city, faced on a daily basis. Dickens had dined in his restaurant; he had sent Queen Victoria some of his choicest oysters and she had thanked him by having a gold chronometer watch delivered to him. Yet racism dogged Downing at every turn. Mobs had assaulted his establishment on more than one occasion. A jealous competitor had tried to destroy his business by writing a letter to the

New York Post

in which he proposed that city newspapers issue a public denunciation of Downing’s abolitionist sentiments and call for a public meeting “to proscribe all negroes who sell oysters, and all white people who eat oysters sold by them.” Only then, the competitor concluded, “I might get my stale stock off my hands, and soon afford to supply a fresh article on moderate terms, and, at the same time, receive a just reward for my devotion to the constitution.”

58

Philip was also aware that Downing fretted over the fact that racism forced him to discourage blacks from patronizing his restaurant. His own light skin would not attract notice, but this was not an option for darker-skinned blacks. Philip remembered the uproar that Charles

Reason and Alexander Crummell had caused years earlier when they had written several angry letters to the

Colored American

publicly excoriating their friend Thomas van Rensselaer for refusing to seat blacks in his restaurant or for trying to “colonize” them by placing them behind a screen or relegating them to the kitchen.

59

Putting these troubling thoughts aside, Philip enjoyed his plate of oysters, then left, promising Downing that he would deliver some papers to his son.

Heading north, Philip decided to visit his old mentor, James McCune Smith, who was confined to his home on North Moore Street suffering from symptoms of congestive heart failure. As he proceeded up Broadway, Philip thought of how well George Foster had captured the contrasts of the avenue in his most recent book. In the morning, Foster noted, Broadway was “hushed and solitary”; the few who were about could amuse themselves watching “the awakened swine gallop furiously downward to have the first cut of the new garbage.” Later in the day, however, a mass of people would surge through the street, “a human river in a freshet, roaring and foaming toward the sea.” Then there were the contrasts of buildings. Among some truly fine structures others had sprung up haphazardly—a brick schoolhouse or a clapboard barn here, a penitentiary or pound there. Finally, what caught your eye depended on where you looked: down, a rotten cellar door; straight ahead, “a plate-glass window stuffed with gaudy cashmeres and mildewed muslims”; above, “an interminable line of crooked well-posts, armed with glass bottles, and held together by wire clothes lines.”

60

Philip paused only to admire Alexander Stewart’s new department store on the corner of Chamber Street. Five stories high and designed in the Italianate style, it resembled a Renaissance palace: white marble exterior, Corinthian columns on the ground floor, cornice work above the windows, all topped by a dome eighty feet high. Inside, the store stocked a profusion of goods marketed specifically to female customers. But Philip knew one woman who out of loyalty would resist Stewart’s enticements. Grandmother Marshall loved to tell the story of how the English immigrant Samuel Lord teamed up with George Washington Taylor in 1826 and opened a store on Catherine Street to sell “plaid silks for misses’ wear, hosiery, and elegant Cashmere long shawls.” On opening day “she hurried over to make an early purchase, of a yard of white

ribbon, to give the ‘boys’ good luck, for she knew them both well.”

61

She was not about to desert them now.

Turning west off Broadway to get to Smith’s home in the Fifth Ward around St. John’s Park, Philip was once again reminded of the city’s contrasts, in this instance of changes wrought over time. In his childhood, this neighborhood had been highly fashionable and home to some of New York’s best families. The park was among the finest in the city, ringed by mature trees and handsome Federal style rowhouses, and graced on its east side by the elegant St. John’s Chapel. But the pressure of commercialization from both downtown and the Hudson River waterfront had precipitated the flight of the “upper tendom” farther north, above Bleecker Street. Smith had been fortunate enough to buy a good brick house on North Moore Street, one block south of the park.

62

Since Smith was tired, Philip made his visit brief.

Philip’s final destination was George Downing’s catering establishment on Bond Street above Bleecker in the Fifteenth Ward. He traced his steps back to Broadway and proceeded north across Canal, thinking of how this section of the avenue offered a set of contrasts different still than those mentioned by Foster. He knew that come nightfall the entire area up to Houston Street would be overrun with people, customers in search of good food, good drink, good entertainment, and yes, good sex. The area had become a center of the city’s sex trade. Prostitutes were everywhere: in hotels, in private supper rooms of restaurants, in upstairs drinking rooms of saloons, in brothels that lined the side streets, on the streets where they handed out calling cards. Walt Whitman was certain that in no other place could vice show itself so “impudently.”

63

Except for the amount of money that traded hands, how different, Philip wondered wryly, was this sex trade from that found in the Five Points?

Crossing Bleecker, Philip reached the Bond Street/LaFayette Place area where the white elite—the Wards, Lows, Minturns, Schermerhorns, and others—had settled. The neighborhood was quiet and secluded; large trees shaded the houses from the inquisitive gaze of passers-by. Philip was intensely proud that some in the black community had managed to set up shop amid such exclusivity. George Downing’s store was at 690 Broadway; his ads in the

Tribune

, which boasted

such specialties as pickled oysters and boned turkey, were directed at both black and white customers.

64

Patrick Reason’s engraving shop was on Bond Street itself, at number 56; the street’s residents were patrons of the arts, and Patrick undoubtedly owed much of his commercial success to them.

Philip knew that the white elite willingly patronized the best black businesses. So maybe, he thought, as he entered Downing’s store, Frederick Douglass was right when he opined in a

North Star

editorial that black New Yorkers were now seeing “the accursed load of popular contempt and scorn by which we have been weighed down for centuries, gradually diminishing. They see the violent waves of malignant prejudice slowly but surely subsiding; the long despised race to whom they belong, steadily rising in position, and rapidly gaining respect and consideration.”

65

Whimsy and Resistance

CIRCA 1853

FREDERICK DOUGLASS WAS

dead wrong. Instead of bearing witness to the waning of racial prejudice, the 1850s gave birth to what we commonly call “scientific racism.” At first, its proponents simply referred to it as “the nigger business.” Then, when they began to fancy themselves men of science and sought to endow their work with gravitas, they coined the term “niggerology.” Consider some of the scientific arguments made by proslavery southerners.