Blood Brotherhoods (11 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

The reason why the armed crowd that attacked the police stations showed such remarkable self-discipline was that many of them were

camorristi

allied with the patriots, who wanted to take the Bourbon police out of the game, but did not want the city to descend into anarchy.

La Sangiovannara

was a key figure here. She was rumoured to have helped patriotic prisoners smuggle messages out of Bourbon jails. More importantly, she was camorra boss Salvatore De Crescenzo’s cousin. As our Swiss hotelier Marc Monnier said of her

Without being affiliated to the Society, she knew all of its members and brought them together at her house for highly risky secret parleys.

The parleys between the patriots and the camorra entered a new phase once the Neapolitan police force melted away, and Liborio Romano took control of enforcing order in the city. Why did Romano ask the camorra to police Naples? Several different theories circulated in the aftermath. Marc Monnier, generous soul that he was, gave a very charitable explanation. Romano, like his father before him, was a Freemason, as were some other patriotic leaders, as indeed was Garibaldi himself. The typical Masonic cocktail of fellowship, high ideals and ritualistic mumbo-jumbo fitted very well with the seemingly far-fetched project of creating a common

Patria

out of Italy’s disjointed parts. Garibaldi’s conquest of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies seemed to be turning those ideals into a reality. Perhaps, argued Monnier, Liborio Romano saw the Honoured Society as a primitive version of his own sect, and hoped it could be turned to the same humanitarian ends. Perhaps.

Less generous and much more realistic commentators said simply that the camorra threatened Romano that they would unleash anarchy on the streets unless they were recruited into the police. It was also claimed that the camorra threatened to kill Romano himself. Other voices—bitter Bourbon supporters it must be said—claimed that Romano was not threatened at all, and that he and some other patriots were the camorra’s willing partners all along.

For several years Romano squirmed silently as others tried to make sense of what he had done. Over time, his public image as the saviour of Naples was upended. Most opinion-formers came to regard him as cynical, corrupt and vain; the consensus was that Romano had colluded with the camorra all along. Finally, several years later, Romano made his bid to tell his side of the story and to magnify his history-making role in the turbulent summer of 1860. But his memoir, with its mixture of self-dramatisation and evasive bluster, only served to fuel the worst suspicions, showing that at the very least he was a man with a great deal to hide.

Romano’s explanation of how he persuaded the camorra to replace the Bourbon police is so wooden and devious as to be almost comic. He could have reasoned that Naples was an unruly city, and that to keep the peace after the fall of the Bourbons he had had to resort to any means necessary—including recruiting criminals into the police. Few would have criticised him if he had opted for that line of argument. But instead, Romano set out a curious story. He tells us that he asked the most famous

capo

of the Honoured Society to meet him in his office at the Prefecture. Face-to-face with the notorious crook, Romano began with a stirring speech. He explained that the previous government had denied all routes to self-improvement for hardworking people with no property. (The

camorrista

could be forgiven a blush of recognition as it sank in that this meant him.) Romano pressed on: the men of the Honoured Society should be given a chance to draw a veil over their shady past and ‘rehabilitate themselves’. The best of them were to be recruited into a refounded police force that would no longer be manned by ‘nasty thugs and vile stoolpigeons, but by honest people’.

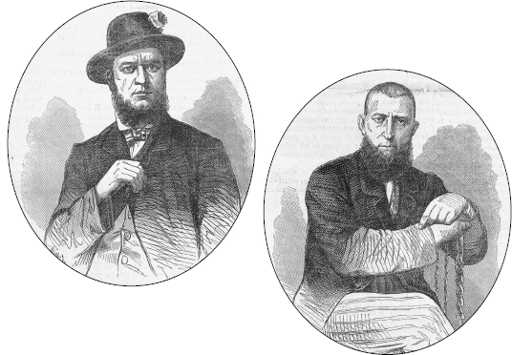

Two more redeemed

camorristi

: Michele ‘the Town Crier’ (left) and ‘Master Thirteen’ (right).

Romano tells us that the mob boss was moved to tears by this vision of a new dawn. Camorra legend has it that he was none other than Salvatore De Crescenzo.

The tale is far-fetched enough to be a scene from an opera. Indeed the whole memoir is best read in precisely that way: as an adaptation, written to impose a unity of time, place and action—not to mention a sentimental gloss—on the more sinister reality of the role that both Liborio Romano and the camorra played in the birth of a united Italian nation. The likelihood is that Romano and the Honoured Society were hand in glove from the outset. The likelihood is, in other words, that Romano and the camorra together planned the destruction of the Neapolitan police force and its replacement by

camorristi

.

Ultimately the precise details of the accord that was undoubtedly struck between gangsters and patriots do not matter. As events in Naples would soon prove, a pact with the devil is a pact with the devil, whatever the small print says.

U

NCLE

P

EPPE

’

S STUFF

: The camorra cashes in

T

HE LAST

B

OURBON

K

ING OF

N

APLES ABANDONED HIS CAPITAL ON

6 S

EPTEMBER

1860.

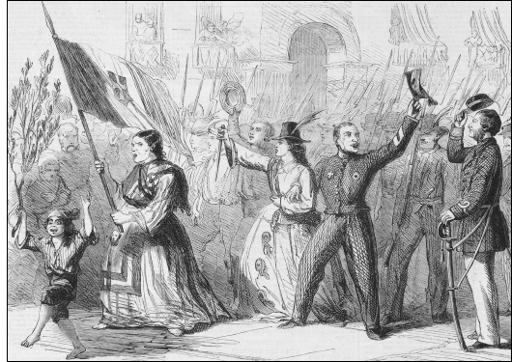

The following morning, the city’s population poured into the streets and converged on the station to hail the arrival of Giuseppe Garibaldi. Bands played, banners fluttered. Ladies of the highest rank mixed with the rankest plebs, and everyone shouted ‘viva Garibaldi!’ until they could do little more than croak. Marc Monnier left his hotel early to join the throng. ‘I didn’t believe that national enthusiasm could ever make so much noise’, he recorded. Through a gap in the rejoicing multitude he glimpsed Garibaldi from close enough to make out the smile of tired happiness on his face. He did not have to peer to see

la Sangiovannara

, with her large following of armed women. Or indeed the

camorristi

who stood above the crowd in their carriages, waving weapons in the air.

Liborio Romano shared Garibaldi’s glory. The camorra’s great friend had been the first to shake Garibaldi’s hand on the platform at Naples station; the two of them later climbed into the same carriage and rode together through the rejoicing crowds.

A French journalist found

la Sangiovannara

(with flag) hard to pin down: ‘a young woman’s innocent smile alternates on her face with a wolfish cackle’. He described her tavern, adorned with patriotic flags and religious icons, as a hang-out for thugs. He did not know that she was a powerful figure in the Neapolitan underworld.

Garibaldi’s Neapolitan triumph was also the cue for ‘redeemed’ camorra bosses like Salvatore De Crescenzo to cash in on the power they had won, and to turn their tricolour cockades into a licence to extort. After Garibaldi arrived in Naples a temporary authority was set up to rule in his name while the south’s incorporation into the Kingdom of Italy was arranged. The short period of Garibaldian rule saw the camorra reveal its true, unredeemed self. As Marc Monnier wryly noted

When they were made into policemen they stopped being

camorristi

for a while. Now they went back to being

camorristi

but did not stop being policemen.

The

camorristi

now found extortion and smuggling easier and more profitable than ever. Maritime contraband was a particular speciality of Salvatore De Crescenzo’s—he was the ‘the sailors’

generalissimo

’, according to Monnier. While his armed gangs intimidated customs officials, he is said to have imported enough duty-free clothes to dress the whole city. A less well-known but no less powerful

camorrista

, Pasquale Merolle, came to dominate illegal commerce from the city’s agricultural hinterland. As any cartload of wine, meat or milk approached the customs office, Merolle’s men would form a scrum around it, shouting ‘

È roba d’ o si Peppe

’. ‘This is Uncle Peppe’s stuff. Let it through’. Uncle Peppe being Giuseppe Garibaldi. The

camorra established a grip on commercial traffic with frightening rapidity; the government’s customs revenue crashed. On one day only 25

soldi

were collected: enough to buy a few pizzas.

The camorra also found entirely new places to exert its influence. Hard on the public celebrations for Garibaldi’s arrival there followed widespread feelings of insecurity. Naples was not just a metropolis of plebeian squalor. It was also a city of place-seekers and hangers-on, of underemployed lawyers and of pencil-pushers who owed their jobs to favours dished out by the powerful. Much of Naples’s precarious livelihood depended heavily on the Bourbon court and the government. If Naples lost its status as a capital it would also forfeit much of its economic

raison d’être

. People soon began wondering whether their jobs would be safe. A purge, or just a wave of carpet-baggers eager to give jobs to their friends could bring unemployment for thousands. But if no job seemed safe, then no job seemed beyond reach either. The sensible thing to do was to make as much fuss as possible and to constantly harass anyone in authority. That way you were less likely to be forgotten and shunted aside when it came to allocating jobs, contracts and pensions.

In the weeks following Garibaldi’s triumphant entry the ministers and administrators trying to run the city on his behalf had to fight their way through crowds of supplicants to get into their offices.

Camorristi

were often waiting at the head of the queue. Antonio Scialoja, the economist who had written such an incisive analysis of the camorra back in 1857, returned to Naples in 1860 and witnessed the mess created under Garibaldi’s brief rule.

The current government has descended into the mire, and is now smeared with it. All the ministers have dished out jobs hand over fist to anyone who pleads loudly enough. Some ministers have reduced themselves to holding court surrounded by those scoundrel chieftains of the people that are referred to here as

camorristi

.

‘Some ministers’ undoubtedly included Liborio Romano. Not even under the discredited Bourbons had

camorristi

had such opportunities to turn the screws of influence and profit.

S

PANISHRY

: The first battle against the camorra

O

N

21 O

CTOBER

1860,

AN AUTUMN

S

UNDAY BLESSED WITH JOYOUS SUNSHINE AND A

clear blue sky, almost every man in Naples voted to enter the Kingdom of Italy. The scenes in the city’s biggest piazza—later to be re-baptised Piazza del Plebiscito (Plebiscite Square) in memory of that day—were unforgettable. The basilica of San Francesco di Paola seemed to stretch its vast semicircular colonnade out to embrace the crowds. Under the portico, a banner reading ‘People’s assemblies’ was stretched between the columns. Beneath there were two huge baskets labelled ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

In incalculable numbers, yet with patience and good humour, the poorest Neapolitans waited their turn to climb the marble steps and vote. Ragged old men too infirm to walk were carried, weeping with joy, to deposit their ballot in the ‘Yes’ basket. The tavern-owner, patriotic enforcer and camorra agent known as

la Sangiovannara

was again much in evidence. She was even allowed to vote—the only woman given such an honour—because of her services to the national cause. Etchings of her strong features were published in the press: she was ‘the model of Greco-Neapolitan beauty’ according to one observer.