Blood Brotherhoods (7 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

A united Italy was still a formless dream when Duke Sigismondo Castromediano was clapped in irons in 1851. But as his traumatic first hours in prison turned into days, months, and years, he found sources of resilience to add to his political dreams: the companionship of his fellows in degradation; but also a determination to understand his enemy. For the Duke of Castromediano, making sense of the camorra was a matter of life and death.

His discoveries should be ours, since they still hold good today. In prison, Castromediano was able to observe the early camorra in laboratory conditions as it perfected a criminal methodology destined to infiltrate and subvert the very nation that Duke Castromediano suffered so much to create.

Castromediano began his study of the camorra in the most down-to-earth way: he followed the money. And the thing that most struck him about what he called the camorra’s ‘taxes’ was that they were levied on absolutely every aspect of a prisoner’s life, down to the last crust of bread and the most miserable shred of clothing.

At one end of most dungeons in the Kingdom was a tiny altar to the Madonna. The first tax extracted from a newly arrived prisoner was often claimed as a payment for ‘oil for the Madonna’s lamp’—a lamp that rarely, if ever, burned. Prisoners even had to rent the patch of ground where they slept. In prison slang, this sleeping place was called a

pizzo

. Perhaps not coincidentally, the same word today means a bribe or a protection payment. Anyone reluctant to pay the

pizzo

was treated to punishments that ranged from insults, through beatings and razor slashes, to murder.

Duke Sigismondo Castromediano, who analysed the camorra’s methods while in prison in the 1850s. He called it ‘one of the most immoral and disastrous sects that human infamy has ever invented’.

Duke Castromediano witnessed one episode that illustrates how the camorra’s prison funding system involved something far more profound than brute robbery—and something much more sinister than taxation. On one occasion a

camorrista

, who had just eaten ‘a succulent soup and a nice hunk of roast’, threw a turnip into the face of a man whose meagre ration of bread and broth he had confiscated in lieu of a bribe. Insults were hurled along with the vegetable.

Here you go, a turnip! That should be enough to keep you alive—at least for today. Tomorrow the Devil will take care of you.

The camorra turned the needs and rights of their fellow prisoners (like their bread or their

pizzo

) into favours. Favours that had to be paid for, one way or another. The camorra system was based on the power to grant those favours and to take them away. Or even to throw them in people’s faces. The real cruelty of the turnip-throwing episode is that the

camorrista

was bestowing a favour that he could just as easily have withheld.

Duke Castromediano had an acute eye for episodes that dramatised the underlying structures of camorra power in the prisons. He once overheard two prisoners arguing about a debt. There were only a few pennies at stake. But before long, a

camorrista

intervened. ‘What right have you got to have an argument, unless the camorra has given you permission?’ With that, he seized the disputed coins.

Any prisoner who asserted a basic right—like having an argument or breathing air—was insulting the camorra’s authority. And any prisoner who tried to appeal for justice to an authority beyond the prison was committing treason. The Duke met one man who had had his hands plunged into boiling water for daring to write to the government about prison conditions.

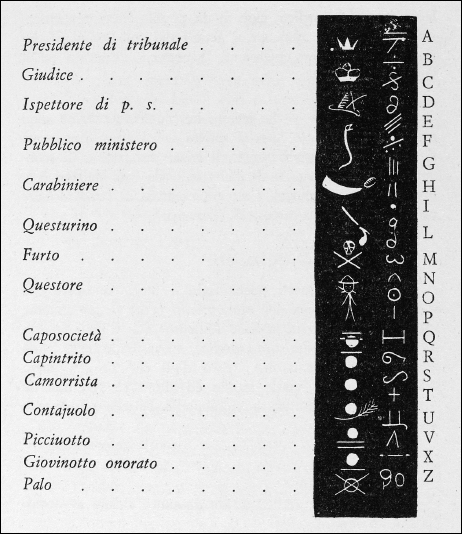

Camorra code book. Reportedly confiscated from a prison

camorrista

who kept it secreted in his anus, this secret table explains the symbols

camorristi

used in messages they smuggled in and out of prison. From a nineteenth-century study of the Honoured Society of Naples.

Much of what Castromediano learned about the camorra came from his time in a prison on Procida, one of the islands that, like its beautiful sisters Capri and Ischia, is posted at the mouth of the Bay of Naples. When he later looked back at his time on Procida, the Duke unleashed an undigested anger.

The biggest jail in the southern provinces. The queen of jails, the camorra’s honey pot, and the fattest feeding trough for the guard commanders and anyone else who has a hand in supporting the camorra; the great latrine where, by force of nature, society’s most abominable scum percolates.

It was in Procida prison’s own latrine, which fed straight into the sea, that the Duke came across another crucial facet of the camorra system. One day he noticed two human figures sketched in coal on the wall. The first had wide, goggling eyes and a silent howl of rage issuing from his twisted mouth. With his right hand he was thrusting a dagger into the belly of the second, who was writhing in excruciating pain as he keeled over. Each figure had his initials on the wall above his head. Below the scene was written, ‘Judged by the Society’, followed by the very date on which the Duke had come across it.

Castromediano already knew that the Society or Honoured Society was the name that the camorra gave itself. But the doodle on the wall was obscure. ‘What does that mean?’ he asked, with his usual candour, of the first person he came across.

It means that today is a day of justice against a traitor. Either the victim drawn there is already in the chapel, breathing his last. Or within a few hours the penal colony on Procida will have one less inmate, and hell will have one more.

The prisoner explained how the Society had reached a decision, how its bosses had made a ruling, and how all members except for the victim had been informed of what was about to happen. No one, of course, had divulged this open secret.

Then, just as he was warning the Duke to keep quiet, from the next corridor there came a loud curse, followed by a long and anguished cry that was gradually smothered, followed in turn by a clinking of chains and the sound of hurried footsteps.

‘The murder has happened,’ was all that the other prisoner said.

In a panic, the Duke bolted for his own cell. But he had hardly turned the first corner when he stumbled upon the victim, three stab wounds to his heart. The only other person there was the man the victim was chained to. The man’s attitude would remain seared into Castromediano’s memory. Perhaps he was the killer. At the very least he was an eyewitness. Yet he gazed down at the corpse with ‘an indescribable combination of stupidity and ferocity’ as he waited calmly for the guards to bring the hammer and anvil they needed to separate him from his dead companion.

Castromediano called what he had witnessed a ‘simulacrum’ of justice; this was murder in the borrowed clothes of capital punishment. The camorra

not only killed the traitor. More importantly, it sought to make that killing legitimate, ‘legal’. There was a trial with a judge, witnesses, and advocates for the prosecution and the defence. The verdict and sentence that issued from the trial were made public—albeit on the walls of a latrine rather than in a court proclamation. The camorra also sought a twisted form of democratic approval for its judicial decisions, by making sure that everyone bar the victim knew what was about to take place.

The camorra courts did not reach their decisions in the name of justice. Rather, their lodestar value was

honour

. Honour, in the sense that the Society understood it (a sense that Castromediano called an ‘aberration of the human mind’), meant that an affiliate had to protect his fellows at all costs, and share his fortunes with them. Disputes had to be resolved in the approved fashion, usually by a dagger duel; oaths and pacts had to be respected, orders obeyed, and punishment accepted when it was due.

Despite all the talk of honour, the reality of camorra life was far from harmonious, as Castromediano recalled.

Relations between those accursed men seethed with arguments, hatred, and envy. Sudden murders and horrible acts of vengeance were perpetrated every day.

A murder committed as a vendetta was a murder to defend one’s personal honour, and as such it could easily be sanctioned by the camorra’s shadow judicial system. Quite whether a vendetta was legitimate or not depended partly on the Society’s rules and legal precedents, which were transmitted orally from one generation of criminals to the next. More importantly, it depended on whether the vendetta was committed by a

camorrista

fearsome enough to impose his will. In the prison camorra, even more than anywhere else, the rules were the tool of the rich and powerful. Honour was law for those who placed themselves above the law.

Camorra ‘taxation’. Camorra ‘justice’. Castromediano also talks of the camorra’s ‘jurisdiction’, its ‘badges of office’, and its ‘administration’. His terminology is striking, consistent and apt: it is the vocabulary of state power. What he is describing is a system of criminal authority that apes the workings of a modern state—even within a dungeon’s sepulchral gloom.

If the camorra of the prisons was a kind of shadow state, it had a very interventionist idea of how the state should behave. Duke Castromediano saw that

camorristi

fostered gambling and drinking in the full knowledge that these activities could be taxed. (Indeed the practice of taking bribes from gamers was so closely associated with gangsters that it generated a popular theory about how the camorra got its name.

Morra

was a game, and the

capo della morra

was the man who watched over the players. It was said that this title was shortened at some stage to

ca-morra

. The theory is probably apocryphal: in Naples,

camorra

meant ‘bribe’ or ‘extortion’ long before anyone thought of applying the term to a secret society.)

Card games and bottles of wine generated other moneymaking opportunities: the camorra provided the only source of credit for unlucky gamblers, and it controlled the prison’s own stinking, rat-infested tavern. Moreover, every object that the camorra confiscated from a prisoner unable to afford his interest payments, his bottle, or his bribe, could be sold on at an eye-watering markup. The dungeons echoed to the cries of pedlars selling greasy rags and bits of stale bread. A whole squalid economy sprouted from exploiting the prisoners at every turn. As an old saying within the camorra would have it, ‘

Facimmo caccia’ l’oro de’ piducchie

’: ‘We extract gold from fleas.’

The camorra system also reached up into the prisons’ supposed command. Naturally, many guards were on the payroll. This corruption not only gave the camorra the freedom it needed to operate, it also put even more favours into circulation. For a price, prisoners could wear their own clothes, sleep in separate cells, eat better food, and have access to medicine, letters, books and candles. By managing the traffic in goods that came in and out of prison, the camorra both invented and monopolised a whole market in contraband items.

So the prison camorra had a dual business model designed to extract gold from fleas: extortion ‘taxes’ on the one hand and contraband commerce on the other. The camorra of today works on exactly the same principles. All that has changed is that the ‘fleas’ have become bigger. Bribes once taken on a place to lay a mattress are now cuts taken on huge public works contracts. Candles and food smuggled into prison are now consignments of narcotics smuggled into the country.

Duke Castromediano’s years as a political prisoner were spent in several jails but everywhere he went he found the camorra in charge. So his story is not just about the origins of what today is called the

Neapolitan

camorra. Prisoners from different regions mingled in jails across the southern part of the Italian peninsula, on Sicily, and on many small islands. They all referred to themselves as

camorristi

.

The Duke did however notice distinctions in the dress code adopted by

camorristi

from different regions. Sicilians tended to opt for the black plush look. (The

camorrista

who introduced himself to the Duke on his first day in the Castello del Carmine was Sicilian.) Not long before, Neapolitans had dressed in the same way. But for some time now they had preferred to signal their status with clothes that could come in any colour, as long as it was of

good quality and accessorised in gold: gold watch and chain; gold earrings; chunky gold finger rings; all topped off with a fez decorated with lots of braid, embroidery and a golden tassel.