Blood Brotherhoods (9 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

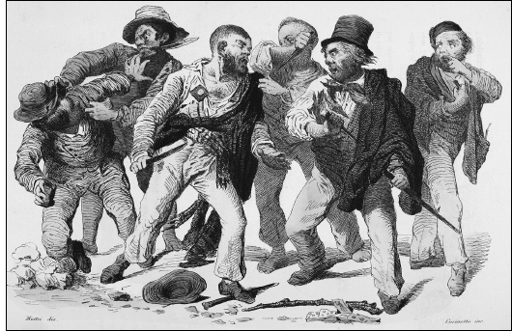

Camorristi

settle their differences over a card game; gambling was one of the Honoured Society’s primary rackets.

With all these opportunities for illegal income close to hand in the Vicaria, it is not surprising that the first supreme bosses of the Honoured Society in the outside world came from here.

The ‘co-management’ of crime in Naples was indeed scandalous. But the exiled economist Antonio Scialoja was particularly angered by the way the Bourbon authorities gave their spies,

feroci

and

camorristi

a free rein to harass and blackmail liberal patriots. In fact these rough and ready cops were no respecters of political affiliation: even Bourbon royalists had to cough up to avoid what the

feroci

smilingly called ‘judicial complications’. In this way, amid the uncertainties of the 1850s, with the Bourbon monarchy vulnerable and wary, the camorra was given the chance to meddle in politics.

Scialoja concluded his pamphlet with an exemplary tale drawn from his own memories of life as a political prisoner in the early 1850s. He recalled that the common criminals in jail referred to the captive patriots simply as ‘the gentlemen’, because their leaders were educated men of property like him. But by no means everyone who got mixed up in liberal politics was a gentleman. Some were tough artisans. A case in point was one Giuseppe D’Alessandro, known as

Peppe l’aversano

—‘Aversa Joe’ (Aversa being an agricultural settlement not far north of Naples). Aversa Joe was sent to jail for his part in the revolutionary events of 1848. When he encountered the camorra, he quickly decided that joining the ranks of the extortionists was preferable to suffering alongside the gentlemen martyrs. He was initiated into the Honoured Society and was soon swaggering along the corridors in his flares.

In the spring of 1851, at about the time when Gladstone was thundering about the

gamorristi

to his British readers, one particularly zealous branch of the Neapolitan police conceived a plan to kill off some of the incarcerated patriots. But not even the police could carry out such a scheme without help from the prison management—the camorra. In Aversa Joe they found the perfect man for the job; in fact they didn’t even have to pay him since he was still under sentence of death for treason and was glad simply to be spared his date with the executioner.

Aversa Joe twice attempted to carry out his mission, with a posse of

camorristi

ready to answer his call to attack. But both times the gentlemen managed to stick together and face down their would-be killers.

The political prisoners then wrote to the police authorities to remind them of the diplomatic scandal that would ensue if they were torn to pieces by a mob. The reminder worked. Aversa Joe was transferred elsewhere, then released, and finally given the chance to swap his velvet jacket for a police uniform: he had completed the transformation from treasonable patriot, to

camorrista

, to policeman in the space of a couple of years.

For Scialoja, the Aversa Joe story typified everything that was bad about Bourbon rule, with its habit of co-managing crime with mobsters. The Italian

Patria

would stand in shining contrast to such sleaze. The new nation of Italy, whenever it came, would finally bring good government to the benighted metropolis in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius.

But Naples being Naples, forming the

Patria

turned out to be a much stranger and murkier business than anyone could have expected.

T

HE REDEMPTION OF THE CAMORRA

T

HE SUMMER OF

1860

WAS THE SUMMER OF

G

ARIBALDI

’

S EXPEDITION

,

WHEN MARVELS

of patriotic heroism finally turned the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies into part of the Kingdom of Italy. In Naples, history was being made at such a gallop that journalists scarcely had time to dwell on what they saw and heard. This was a moment when the incredible seemed possible, and thus a time for narrative. Explanation would have to wait.

There was consternation in Naples when news broke that Garibaldi and his Thousand redshirted Italian patriots had invaded Sicily. On 11 May 1860 the official newspaper announced that what it called Garibaldi’s ‘freebooters’ had landed in Marsala. By the end of the month it was confirmed that the insurgent forces had gained control of the Sicilian capital, Palermo.

The ineffectual young king, Francesco II, was scarcely a year into his reign. As the

garibaldini

consolidated their grip on Sicily and prepared to invade the Italian mainland and march north, Francesco dithered in Naples and his ministers argued and schemed.

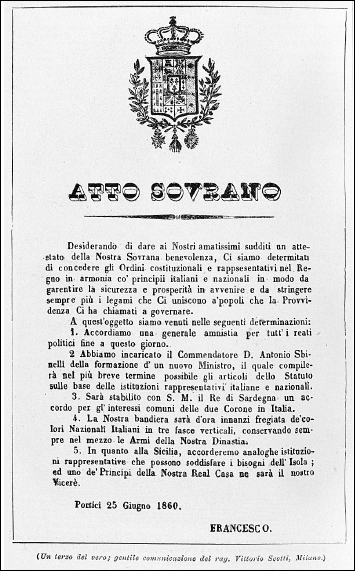

Only on 26 June did Neapolitans find out how the Bourbon monarchy planned to respond to the crisis. Early that morning, posters were plastered along the major streets proclaiming a ‘Sovereign Act’. King Francesco decreed that the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was to cease being an absolute monarchy and embrace constitutional politics. A government comprising liberal patriots had already been formed. There would also be an amnesty for all political prisoners. And the flag would henceforth comprise the Italian tricolour of red, white and green, surmounted by the Bourbon dynasty’s coat of arms.

The early risers who came across the Sovereign Act on the morning of 26 June were afraid to be seen reading it: there was always the chance that it was a provocation intended to force liberals out into the open, and make them easy targets for the

feroci

. But within hours Neapolitans had absorbed what the posters really meant: the Sovereign Act was a feeble and desperate attempt to cling onto power. The gathering momentum of Garibaldi’s expedition had put Francesco in a hopeless position, and the Bourbon state was tottering.

The day the Sovereign Act was published was a bad day to be a policeman in Naples. For years the police had been feared and despised as corrupt instruments of repression. Now they were left politically exposed when there was almost certain to be a battle for control of the streets.

The evening of the day that the Sovereign Act posters appeared, clusters of people from the poorest alleyways came down onto via Toledo to jeer and whistle at the police. Shopkeepers pulled down their shutters and expected the worst. They had good reason to be afraid. Mass disorder visited Naples with what seemed like seasonal regularity, and pillaging inevitably accompanied it.

Serious trouble began the following afternoon. Two rival proletarian crowds were looking for a confrontation: the royalists yelling ‘long live the King’, and the patriots marching to the call of ‘viva Garibaldi’. One colourful character, difficult to miss in the mêlée, was Marianna De Crescenzo, who went by the nickname of

la Sangiovannara

. One report described her as being ‘decked out like a brigand’, festooned in ribbons and flags. Responding to her yelled commands was a gang of similarly attired women brandishing

knives and pistols. Loyalists to the Bourbon cause suspected that

la Sangiovannara

had stoked up the trouble by handing out cheap booze from her tavern, as well as large measures of subversive Italian propaganda.

The pivotal figure in the murky Neapolitan intrigues of 1860. At age 30, Marianna De Crescenzo, a.k.a.

la Sangiovannara

, was a prosperous tavern owner who became famous for her charismatic leadership of the patriotic mob.

On via Toledo, two police patrols found themselves caught between the factions. When an inspector gave the unenforceable order to disarm the crowd, fighting broke out. Some onlookers heard shots. After a running battle, the police were forced to withdraw. Only the arrival of a cavalry unit prevented the situation degenerating even further.

There were two notable casualties of the clash. The first was the French ambassador, who was passing along via Toledo in his carriage when he was accosted and cudgelled. Although he survived, no one ever discovered who was responsible for the attack.

The second victim was Aversa Joe, the patriot, turned prison

camorrista

, turned Bourbon assassin, turned policeman. He was stabbed at the demonstration and then hacked to death while he was being carried to hospital on a stretcher. The murder was clearly planned in advance, although again the culprits remained unknown.

Everyone thought that this was only the overture to the coming terror. Fearing the worst, many policemen ran for their lives. There was no one left to resist the mob. Organised gangs armed with muskets, sword-sticks, daggers and pistols visited each of the city’s twelve police stations in turn; they broke down the doors, tossed files and furniture out of the windows, and lit great bonfires in the street.

The Neapolitan police force had ceased to exist.

But by the afternoon, a peculiar calm had descended. The London

Times

correspondent felt safe enough to go and see the ruined police station in the Montecalvario quarter and found the words ‘DEATH TO THE COPS!’ and ‘CLOSED DUE TO DEATH!’ scrawled on either side of the entrance. These bloodcurdling slogans did not match what had actually happened, though. Witness after witness related how unexpectedly peaceful, ordered and even playful the scenes of destruction were. The mob did rough up the few cops they caught. But instead of lynching their uniformed captives, they handed them over to the army. The

London Daily News

’s man at the scene wrote that, although rumours suggested that many policemen had been murdered, he had been unable to verify a single fatality. Around the bonfires of police paraphernalia there was cheering, laughing and dancing; street urchins cut up police uniforms and handed the pieces out as souvenirs. This was less a riot than a piece of street theatre.

The most unexpected part of it all was that there was no stealing. On every previous occasion when political upheaval had come to Naples, a predatory mob had risen from the low city. Yet this time, outlandishly, rioters from the same slums even handed over any cash and valuables they found to army officers or parish priests. Moving through the streets from one target to the next, they shouted reassurance to the traders cowering behind their shutters. ‘Why close up your shops? We aren’t going to rob you. We only wanted to drive off the cops.’ According to the

Times

correspondent, one man took several watches from the wreckage of a police station. But instead of pocketing them, he threw them on the bonfire burning outside. ‘No one shall say that I stole them’, he proclaimed.