Blood Brotherhoods (2 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

59.

Mafia terror

60.

The fatal combination

61.

Doilies and drugs

62.

Walking cadavers

63.

The capital of the anti-mafia

64.

The rule of non-law

65.

’

U maxi

66.

One step forward, three steps back

67.

Falcone goes to Rome

PART XII:

THE FALL OF THE FIRST REPUBLIC

68.

Sacrifice

69.

The collapse of the old order

70.

Negotiating by bomb: Birth of the Second Republic

PART XIII:

THE SECOND REPUBLIC AND THE MAFIAS

71.

Cosa Nostra: The head of the Medusa

72.

Camorra: A geography of the underworld

73.

Camorra: An Italian Chernobyl

74.

Gomorrah

75.

’Ndrangheta: Snowstorm

76.

’Ndrangheta: The Crime

77.

Welcome to the grey zone

Acknowledgements

Illustration credits

Notes on sources

Sources consulted

Index

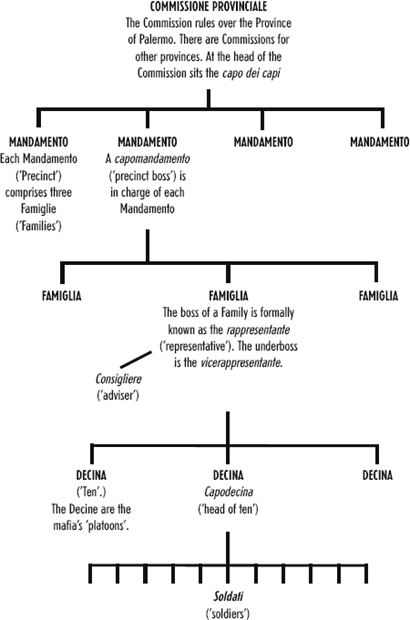

As first described by Tommaso Buscetta in 1984

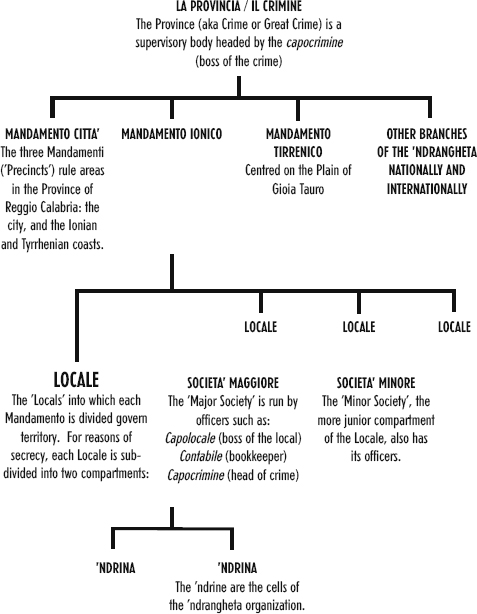

THE STRUCTURE OF THE ’NDRANGHETA

(Source: ‘Operazione Crimine’, summer 2010.)

P

REFACE TO THE

US E

DITION

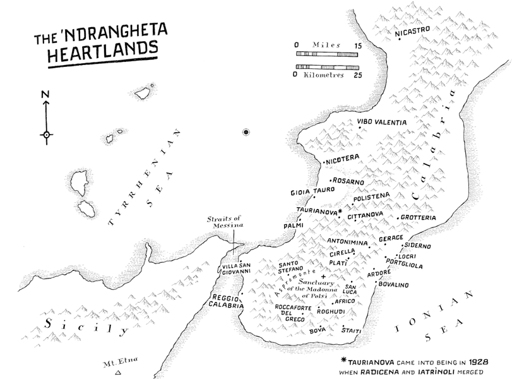

Once upon a time, three Spanish knights landed on the island of Favignana, just off the westernmost tip of Sicily. They were called Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso and they were fugitives. One of their sisters had been raped by an arrogant nobleman, and the three knights had fled Spain after washing the crime in blood.

Somewhere among Favignana’s many caves and grottoes, Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso found sanctuary. But they also found a place where they could channel their sense of injustice into creating a new code of conduct, a new form of brotherhood. Over the next twenty-nine years, they dreamed up and refined the rules of the Honoured Society. Then, at last, they took their mission out into the world.

Osso dedicated himself to Saint George, and crossed into nearby Sicily where he founded the branch of the Honoured Society that would become known as the mafia.

Mastrosso chose the Madonna as his sponsor, and sailed to Naples where he founded another branch: the camorra.

Carcagnosso became a devotee of the Archangel Michael, and crossed the straits between Sicily and the Italian mainland to reach Calabria. There, he founded the ’ndrangheta.

B

LOOD

B

ROTHERHOODS

IS A HISTORY OF

I

TALY

’

S THREE MOST FEARED CRIMINAL

organisations, or mafias, from their origins to the present day. But no historian can claim to be the first person drawn towards the mystery of how the Sicilian mafia, the Neapolitan camorra and the Calabrian ’ndrangheta

began.

Mafiosi

got there first. Each of Italy’s major underworld fraternities has its own foundation myth. For example, the story of Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso (names that mean something like ‘Bone’, ‘Masterbone’, and ‘Heelbone’) is the ’ndrangheta’s official account of its own birth: it is a tale told to Calabrian recruits when they prepare to join the local clan and embark on a life of murder, extortion and trafficking.

As history, the three Spanish knights have about as much substance as the three bears. Their story is hooey. But it is serious, sacramental hooey all the same. The study of nationalism has given us fair warning: any number of savage iniquities can be committed in the name of fables about the past. Moreover, in the course of the last 150 years, Italy’s criminal brotherhoods have frequently occluded the truth by imposing their own narrative on events: all too often the official version of history turns out to derive from the mafias’ myths, which are a great deal more insidious than the hokum about Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso might initially suggest. No ordinary gang, however powerful, has lasted as long as the mafias, nor has it had the same drive to control how its own past is narrated. The very fact that the mafias value history so highly betrays the outrageous scale of their ambition.

Mafia history is filled with many outrages much worse than this. Acts of appalling ferocity are the most obvious. The mafias’ cruelty is essential to what they are and what they do; there is no such thing as a mafia without murder, nor has there ever been. Yet violence is only the beginning. Through violence, and through the many tactics that it makes possible, the mafias have corrupted Italy’s institutions, drastically curtailed the life-chances of its citizens, evaded justice, and set up their own self-interested meddling as an alternative to the courts. So the real outrage of Italy’s mafias is not the countless lives that have been cruelly curtailed—including, very frequently, the lives of the

mafiosi

themselves. Nor is it even the livelihoods stunted, the resources wasted, the priceless landscapes defiled. The real outrage is that these murderers constitute a parallel ruling class in southern Italy. They infiltrate the police, the judiciary, local councils, national ministries, and the economy. They also command a measure of public support. And they have done all this pretty much since the Italian state was founded in 1861. As Italy grew, so too did the mafias. Despite what Fascist propaganda has led many people to believe, the criminal fraternities survived under Mussolini’s regime and even infiltrated it. They prospered as never before with the peace and democracy that have characterised the period since 1946. Indeed, when Italy transformed itself into one of the world’s wealthiest capitalist economies in the 1960s, the criminal organisations

became stronger, more affluent and more violent than ever. They also multiplied and spread, spawning new mafias and new infestations in parts of the national territory that had hitherto seemed immune. Italy is a young country, a modern creation, and the mafias are one of the symptoms of modernity, Italian style.