Blood Lust (18 page)

Authors: Alex Josey

Of course the absence of a body makes a

murder difficult to prove, but a body is not absolutely essential to prove a

murder, providing there is strong circumstantial evidence to explain the

disappearance of a person presumed to have been murdered. Decomposed bodies can

be sometimes identified from dental work, and in other ways. Nevertheless, the

chances of a murderer escaping justice are stronger if there is no body, and

knowing this, the plotters went, shortly before the murders, to Changi to

inspect a suitable disposal area. They went in the dark and their car broke

down. They never went back to make sure there was a deep well in the vicinity.

The Solicitor-General was perhaps right in using the word, ‘irresponsible’, for

the very success of the entire operation depended entirely upon the corpses not

being found for some time, if at all, as Andrew Chou and the others were

quickly to discover. Within a matter of hours after the police found the

bodies, they had all been arrested, and Augustine Ang soon decided that his

only chance of living was to confess all he knew, thus incriminating his close

and intimate friend, Andrew Chou, his confession helping to send Andrew to the

gallows. It was inevitable someone would squeal once the bodies were found:

Augustine was chosen to be the traitor because, after all, he was one of the

principal plotters, and his English was better. He was the best speaker among

them.

None of this would have been necessary—there

might never have been a trial, had the bodies been thoroughly disposed of; yet

planning this side of the crime had received the least attention although

sufficient gangsters had been recruited to throw away the bodies. Nobody had

bothered much about where and how the bodies were to be thrown away. Had this

been done, the Chou brothers and the other seven murderers might still be

alive, and the gold bars melted down.

There is just one other thought. Did the

Chou brothers and Augustine Ang scheme to put the blame on the gangsters they

recruited to throw away the bodies? This was the suggestion put forward by a

counsel on behalf of the boys. He said the plan was for the three older men to

strangle Ngo and his two assistants, and then to implicate the boys, to use

them as stooges. Counsel never explained how he thought the Chou brothers

intended to do this. Such a scheme, if in fact it existed, would of course have

depended upon the Chou brothers and Augustine Ang remaining free and united.

The prompt discovery of the bodies and the rapid arrest of all nine, followed by

Augustine Ang’s decision to tell all to save his neck, ruined immediately any

scheme the principal plotters may have had in mind to blame the boys. Suddenly

everyone was fighting for his own life; personal loyalties disappeared.

Everyone was prepared to blame everybody else. Only the Chou brothers supported

each other. They had no alternative.

Gold

stopped being the basis

for international money when

President Nixon suspended the Bretton Woods system in 1971. The system had been

operating since 1945 when 44 nations meeting in Bretton Woods, in America,

agreed upon international monetary cooperation. Then the dollar was backed by

gold. Singapore’s Finance Minister, Hon Sui Sen, during a speech in 1980 to

world bankers meeting in the Republic, recalled that the world was then told

that gold was no longer important—that the system was flawed because of gold.

Hon asked: “Were we justified in phasing out the monetary role of gold? The

non-monetary role in future for gold is now legally enshrined in the Articles

of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund. It is legitimate to question

the wisdom of the IMF in supporting the demonetisation of gold. Opposed to

those doing everything possible to phase out gold’s role in the monetary

system, there are now some beginning to be convinced of the need for retaining

it. The recent upsurge in the gold price to a peak of twenty times the last

‘official’ price of US$42.2 per ounce, clearly demonstrated that gold still has

a wide following. Demand came not only from private sources, but, it is

understood, also from official sources, notwithstanding the official

lip-service to gold demonetisation.”

Hon went on to say that a return to a

modified gold standard, or a gold exchange standard would be facilitated

perhaps if current gold prices could be taken as official prices somewhat along

the method of valuation in the European Monetary System. “I recognize that this

is not the most fashionable or orthodox view on gold and its role in the monetary

arena at the moment. I am also aware that there are political and other

difficulties in going back to gold. But a trend was set by the demonstration of

belief in gold in the European Monetary System.” The Finance Minister believed

this was an element of great strength in the EMS. “Given time to eliminate

technical problems of operating the system it would not be surprising to find

the EMS growing in influence. If the European Currency Unit is allowed to

evolve and develop in usage so that it can be freely transacted in

international markets, it may well end the financial world’s search for an

alternative to the dollar.”

Hon was sure that on a national basis,

countries which had built up their gold holdings were better able to meet

present-day political and economic problems and other uncertainties. “The

discipline of gold is salutory, especially for governments.” The man in the

street had refused to accept the propaganda that gold should be demonetised. In

this part of the world the value of gold as money was vividly demonstrated by

the experience of the Vietnamese boat people. Without gold they could not have

escaped their unhappy lot in Vietnam. So, in those countries where governments

show a disinclination to persevere with stabilisation policies, there should be

no surprise if the man in the street turns away from paper currencies—‘to that

much abused barbarous relic, gold’. Perhaps, added the Minister, what was

surprising ‘is that when the Bretton Woods system was cast aside, so many

believed that gold no longer mattered’. The high price of gold in 1979 proved

this to be untrue.

In 1980, Singapore was doing a brisk trade

in gold. In the first quarter of the year, gold worth more than US$400 million

was sold. This was nearly double the nett amount of gold imported by Singapore

in 1979. That year, the Republic imported sixty-five tons of gold (nearly 4 per

cent of the worldwide market). Most of it was re-exported to Indonesia, but 13

tons were believed to be held in Singapore vaults. In 1979, Singapore was the

sixth largest importer of gold in the world bullion market. The USA headed the

list with 265 tons, followed by Italy, 240 tons, West Germany, 160 tons, Japan,

110 tons, Hong Kong, 100 tons, and Singapore, 100 tons. The world total was

1,835 tons.

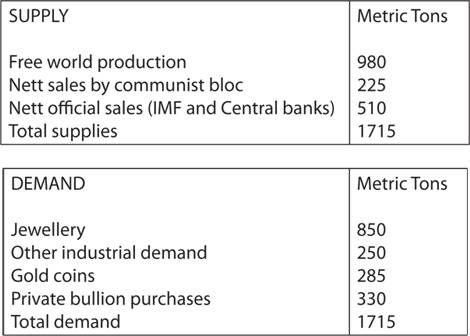

South Africa produced 703 tonnes in 1979

(about the same as in 1978). Altogether the free world is thought to have

produced 980 tonnes of gold in 1979 compared with 969 tonnes in 1978. Nett

communist sales in 1978 were 229 tonnes. In 1979, the figure was 225 tonnes.

Total supplies of gold to the market (including sales by the US Treasury and

the International Monetary Fund) were estimated at 1,765 tonnes compared to

1,752 tonnes in 1978.

It is thought that between 850 and 900 tons

of gold were used in 1979 to make jewellery (1,001 tonnes in 1978).

In 1977 and 1978, about 22–25 per cent of

total gold supply was absorbed by investors in the form of physical gold (gold

bars and coins). In 1979, the figure was estimated to be 36 per cent.

Investors sought gold mainly for the

following three reasons:

·

to hedge against economic and political stability;

·

to diversify assets held in dollars or other vehicles prone to

depreciation in real terms; and

·

to increase the ratio of gold to other assets held in investment

portfolios in an effort to benefit from the contra-cyclical price behaviour of

gold in contrast to other investment assets.

It is interesting to note that in 1979, the

price of gold appreciated in terms of all the major currencies.

It is believed that 330 tons of gold were

purchased by world investors in bullion form in 1979. The Krugerrand remained

the main gold coin sold in world markets in 1979.

Total gold used in the production of

Krugerrands and R2 coins amounted to 145 tonnes during 1979. The British

sovereign absorbed about 50 tonnes, the Canadian Maple Leaf, about 15 tonnes of

gold, the Mexican Peso, about 15 tonnes, the Russian Chervonetz, about 25

tonnes and the Australian Corona, five tonnes of gold. In total, it is

estimated that some 285 tonnes of gold were used to fabricate official gold

coins in 1979, ten per cent more than was used in 1978.

Gold is now traded on a 24-hour basis around

the world.

It is expected that South African mines will

produce 20,000 tonnes of gold in the next 50 years.

WORLD SUPPLY AND DEMAND (1979)

CENTRAL BANK GOLD RESERVES (SEPTEMBER 1979)

There are two ways of

looking at this tragic story of the savage murder of the lovely sensual beauty

queen, Jean SinnappA.

There is the love angle, generated

partly by torrid love letters (some described in Court as being obscene), and

partly by Jean’s own frank attitude towards sex.