Bloody Crimes (16 page)

The doctors agreed that from then on, they would not tinker with Lincoln’s body—no more brandy poured down his throat to see whether he would swallow it or almost choke to death; no more fruitless Nélaton-probe thrusts through the bullet puncture in his skull into his brain to trace, for curiosity’s sake, the wound tunnel and locate the missile. No, all they would do now was watch and wait.

No one at the Petersen house was aware of this yet, but a second assassin had struck in Washington that night. At 10:15

P.M.

, a crazed man with superhuman strength had invaded the home of Secretary of State William H. Seward. The assailant stabbed and slashed Seward—who was bedridden from injuries he had suffered during a recent carriage accident—almost to death, wounded a veteran army sergeant serving as Seward’s nurse, and knifed a State Department messenger. The unknown killer had also, while beating Seward’s son Frederick with a pistol, crushed his victim’s skull and rendered him senseless. Seward’s home was off Lafayette Park near the White House, just a few blocks from Ford’s Theatre.

Runners carried the news of the attack on Seward to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who were at their homes preparing for bed and had not heard about

the assassination of the president. Each man raced by carriage to Seward’s mansion. There, they first heard rumors of another attack, this one upon the president at Ford’s Theatre. Together, Stanton and Welles drove a carriage to Tenth Street and arrived at the Petersen house before midnight. Stanton barreled his way through the crowded hallway. Reeling at the sight of the wounded president, the secretary of war concluded that Lincoln was a dead man. There was nothing he could do for him. Except work. There was much to do. Stanton steeled himself for the long night ahead. He would not spend the night mourning at Lincoln’s bedside.

Welles volunteered to play that role. As news of the assassination spread through Washington, many important public officials made pilgrimages to the Petersen house. Welles decided that at least one man should remain, never to leave Lincoln’s side until the end, to bear witness to his suffering. Stanton could lead the investigation of the crime, interview witnesses, send telegrams, launch the manhunt for Booth and his accomplices, and take precautions to prevent more assassinations later that night.

Welles, on the other hand, would lead the death vigil. And he would record in his diary what he saw: “The giant sufferer lay extended diagonally across the bed, which was not long enough for him. He had been stripped of his clothes. His large arms were of a size which one would scarce have expected from his spare form. His features were calm and striking. I have never seen them appear to better advantage, than for the first hour I was there. The room was small and overcrowded. The surgeons and members of the Cabinet were as many as should have been in the room, but there were many more, and the hall and other rooms in front were full.”

Could it be, Welles wondered, that something the president had said at the White House earlier that day prefigured the assassination? Had Lincoln’s strange dream foretold this tragedy? At the 11:00

A.M

. cabinet meeting, the president said that he expected important news

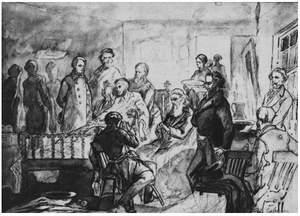

THE PETERSEN HOUSE DEATHBED VIGIL, SKETCHED BY AN ARTIST FROM THE ARMY MEDICAL MUSEUM.

soon. He had experienced, the previous night, a recurring dream that he believed always foretold the coming of great events. Welles preserved the remarkable story in his diary. Lincoln told his cabinet that “he had last night the usual dream which he had preceding nearly every great and important event of the War…the dream…was always the same.” Welles asked Lincoln to describe it.” [I] seemed,” the president recounted, “to be in some singular, indescribable vessel…moving with great rapidity towards an indefinite shore.”

The president said he had this dream preceding the bombardment of Fort Sumter and the battles of Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and more. Had a premonition of his own assassination come to Lincoln in a dream? As Gideon Welles sat beside his dying chief, he did not know that, several days earlier, Lincoln had dreamed a far more vivid nightmare of death.

By midnight the Petersen house had become the cynosure of official Washington. Like a major planet exerting an invisible but irresist

ible gravitational force, the brick home attracted the luminaries who orbited the national capital. Throughout the night, as word spread that the president had suffered a fatal wound, dozens of people—generals, army officers, cabinet secretaries, members of Congress, government officials, and personal friends—made pilgrimages to Tenth Street to augment the bedside vigil and to behold for the last time the stillliving form of Abraham Lincoln. Throughout the night and into the early morning, a steady procession of mourners went to and from the Petersen house. Some, content to gaze upon the president’s face for a few minutes, left shortly after they had done so. Others remained and would not leave until the end. They wanted to watch Abraham Lincoln die.

E

lizabeth Dixon was the first of Mary’s friends to arrive, and the gruesome scene horrified her: “On a common bedstead covered with an army blanket and a colored woolen coverlid lay stretched the murdered President his life blood slowly ebbing away. The officers of the government were there & no lady except Miss Harris whose dress was spattered with blood as was Mrs. Lincoln’s who was frantic with grief calling him to take her with him, to speak one word to her…I held and supported her as well as I could & twice we persuaded her to go into another room.”

Mary never saw many of the visitors who came to the Petersen house that night. The door on the left side of the front hall that opened to the Francises’ front parlor remained half-closed through much of the vigil. Most visitors sped past it on their way to the room at the end of the hall. Some, out of respect, did not wish to intrude upon Mary’s privacy and grief. Others, aware of her unpredictable volatility and proneness to anger, avoided her. After Edwin M. Stanton arrived and decided to occupy the Francis bedroom as his headquarters, and he shut the folding wood doors dividing that space from the front parlor, Mary was sealed off from the activity in the rest of the

house. For most of the night, and through the early morning hours of the next day, Mary remained in semiseclusion, converting the front parlor into her private chamber of solitude, mourning, and, at times, derangement.

For Tad Lincoln, brought home from Grover’s Theatre by the White House doorkeeper, the night of April 14 was filled with terrors. By the time Tad got there, Robert Lincoln had already left to join his parents. Without his mother or older brother to comfort Tad, or even explain to him what had happened to his father, the frightened little boy spent the night alone with servants in the near-empty mansion. All he knew was that a crazy man had burst into Grover’s Theatre, screaming that President Lincoln had been shot, and that the theater manager had also announced the disaster from the stage.

Until the next morning, when Mary and Robert returned to the White House and informed him that his beloved “Pa” was dead, Tad relived the fear and pain he had suffered three years before, when his best companion, his brother Willie, had died. During the long Petersen house death vigil, not once did Robert or Mary go to Tad—even though the White House was just a five-minute carriage ride away and the coachman Francis Burke was ready to whip the president’s carriage through the Tenth Street mob and gallop there. Nor did Robert or Mary order a messenger to retrieve Tad and carry him to the Petersen house and his dying father. It was the first troubling sign of how, in the days to come, Mary’s crippling descent into a mad, gothic, self-absorbed grief caused her to neglect the needs of her inconsolable and lonely little boy.

W

hen Senator Charles Sumner, never close to the president but a confidant of the first lady, heard the news he dismissed it as a wild rumor. When a messenger burst in on him and blurted out, “Mr. Lincoln is assassinated in the theater. Mr. Seward is murdered in his bed.

There’s murder in the streets,” Sumner said he did not believe the news about the president or the attack on Secretary of State Seward.

“Young man,” he said, chastising the messenger, “be moderate in your statements. Tell us what happened.”

“I have told you what has happened,” the man said insistently, and then repeated his story.

When the senator arrived at the Petersen house, he sat down at the head of the bed, held Lincoln’s right hand, and spoke to him. One of the doctors said, “It’s of no use, Mr. Sumner—he can’t hear you. He is dead.”

The senator retorted: “No, he isn’t dead. Look at his face; he is breathing.”

That may be, the doctor admitted, but “it will never be anything more than this.”

Sumner remembered the night’s other victim and asked Major General Halleck, army chief of staff, to drive him to the secretary of state’s mansion. There he found Mrs. Seward sitting on the stairs between the second and third floors. She seized him with both hands and spoke: “Charles Sumner, they have murdered my husband, they have murdered my boy.” Sumner hoped it was not true. He knew firsthand that it was possible to survive a vicious assault. Before the war, a pro-slavery Southern congressman, Preston Brooks, had almost caned Sumner to death in a brutal surprise attack on the Senate floor. Trapped by his desk, Sumner could not rise to fight back or escape and he suffered grievous head wounds. He lived, but recuperation was long and painful, and he did not return to the Senate for three years.

M

any people tried to get inside the Petersen house that night. They pressed against the front wall and stood on tiptoe to peek through the front windows, but the panes were set too high above street level

to allow a clear view into the front parlor. Other people strained toward the stairs, tempted to ascend them and try to get inside. At any moment the crowd might have gone wild, with hundreds of people forcing their way through the doorway. The curved shape of the public staircase and its protective iron railing served as a barricade against frontal assault, impeding any mob attempt to rush the house head-on.

N

ews of the assassination stunned Washington. The local

New York Times

correspondent said it best: “A stroke from Heaven laying the whole of the city in instant ruins could not have startled us as did the word that broke from Ford’s Theatre a half hour ago that the President had been shot.” The Petersen house had become an irresistible magnet, drawing people from all over the city. Soon Major General C. C. Augur, commander of the military district of Washington, and Colonel Thomas Vincent arrived and became impromptu doorkeepers. They admitted only a privileged few into 453 Tenth Street. They denied entry to many: citizen strangers, minor government officials, low-ranking military officers who had no business there, and newspaper reporters.

The motives of the callers varied. Some wanted to express their love for the president. Others wanted to help. Many sought a small place in history—to see the wounded president, to claim they had stood beside his deathbed, to boast to their children and grandchildren that they had been there, or, in the case of the journalists, to be the ones who first reported what happened there. The gatekeepers turned almost all of them away. Indeed, not one journalist made it past them.

Sometime around 2:00

A.M.

, the doctors decided to probe Lincoln’s brain for the bullet. Dr. Leale described what happened:

The Hospital Steward who had been sent for a Nelaton’s probe arrived and an examination of the wound was made by the Surgeon General who introduced it to a distance of about two and a half inches when it came in contact with a foreign substance which laid across the tract of the ball, this being easily passed the probe was introduced further when it again touched a hard substance which was at first supposed to be the ball but the porcelain bulb of the probe did not show the stain of lead upon it after its withdrawal it was generally supposed to be another piece of loose bone. The probe was introduced a second time, and the ball was supposed to be distinctly felt by the Surgeon General, Dr. Stone and Dr. Crane. After this second exploration nothing further was done except to keep the opening free from coagula, which if allowed would soon produce signs of increased compression. The breathing became profoundly stertorous, and the pulse more feeble and irregular.

Throughout the night, Dr. Leale watched Mary stagger from the front parlor into the bedroom: “Mrs. Lincoln accompanied by Mrs. Senator Dixon came into the room several times during the course of the night. Mrs. Lincoln at one time exclaiming, ‘Oh, that my Taddy might see his Father before he died’ and then she fainted and was carried from the room.”

Mary’s pleadings moved Secretary of the Interior John P. Usher: “She implored him to speak to her [and] said she did not want to go to the theatre that night but that he thought he must go…She called for little Tad [and] said she knew he would speak to him because he loved him so well, and after indulging in dreadful incoherences for some time she was finally persuaded to leave the room.”