Bloody Crimes (30 page)

Lincoln’s escape in Baltimore led to public ridicule and false charges: The president had adopted a disguise; he was a coward who had abandoned his wife and children to pass through the city on another train. Cartoonists caricatured Lincoln sneaking through town wearing a plaid Scotch cap and even kilts. Later, he regretted skulking into Washington. It was not an auspicious way to begin a presidency.

Baltimore was home ground for John Wilkes Booth, and he recruited some of his conspirators there. Indeed, a letter found in Booth’s trunk on the night of April 14 suggested that he had multiple conspirators in the city and that he might have sought sanctuary there. It might have been considered obscene to stop the train there, to carry Lincoln’s murdered body into the city that had wished him so much ill and that might revel in his assassination.

Before leaving Washington, General Townsend had sent a telegram to General Morris, who was in command there, giving him advance warning to prepare for the president’s arrival in Baltimore on April 21 and to receive the remains in person.

A

fter a brief stop at Annapolis Station, where Governor A. W. Bradford joined the entourage, the train arrived at Baltimore’s Camden Station at 10:00 a.m. Townsend telegraphed Stanton promptly: “Just arrived all safe. Governor Bradford and General E. B. Tyler joined at Annapolis Junction.” The once unruly city showed no signs of trouble. No lurking secessionists uttered verbal insults against Lincoln or

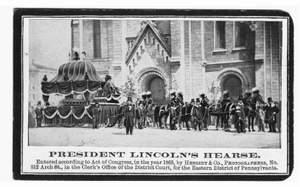

the Union. Instead, thousands of sincere mourners, undeterred by a heavy rain, surrounded the station and awaited the president. The honor guard carried the coffin from the car, placed it in the hearse parked on Camden Street, and the procession got under way, marching to the rotunda of the Merchants’ Exchange. Brigadier General H. H. Lockwood commanded the column, and a number of army officers, including Major General Lew Wallace, who would soon serve as a judge on the military tribunal convened to try Booth’s accomplices, brought up the rear.

The hearse, drawn by four black horses, was designed for the ideal display of its precious passenger. According to a contemporary account, “The body of this hearse was almost entirely composed of plate glass, which enabled the vast crowd on the line of procession to have a full view of the coffin. The supports of the top were draped with black cloth and white silk, and the top of the car was handsomely decorated with black plumes.”

It took three hours for the head of the procession to reach Calvert Street. The column halted, the hearse drove to the southern entrance of the exchange, and Lincoln’s bearers carried him inside. There they laid the coffin beneath the dome, upon a catafalque, around which, Townsend observed, “were tastefully arranged evergreens, wreaths, calla-lilies, and other choice flowers.” Flowers, heaps of flowers, a surfeit of striking and fragrant fresh-cut flowers, would become a hallmark of the funeral journey. Soon, the lilac, above all other flowers, would come to represent the death pageant for Lincoln’s corpse.

The catafalque was made especially for Lincoln. City officials had studied newspaper accounts of the White House funeral two days earlier, and they paid special attention to the descriptions of the extravagant decorations and grand bier. On April 20, while mourners in Washington viewed the remains at the U.S. Capitol, carpenters and other tradesmen in Baltimore built a catafalque to rival the one in the East Room. A contemporary account recorded every detail:

It consisted of a raised dais, eleven feet by four feet at the base, the sides sloping slightly to the height of about three feet. From the four corners rose graceful columns, supporting a cornice extending beyond the line of the base. The canopy rose to a point fourteen feet from the ground, and terminated in clusters of black plumes. The whole structure was richly draped. The floor and sides of the dais were covered with black cloth, and the canopy was formed of black crepe, the rich folds drooping from the four corners and bordered with silver fringe. The cornice was adorned with silver stars, while the sides and ends were similarly ornamented. The interior of the canopy was of black cloth, gathered in fluted folds. In the central point was a large star of black velvet, studded with thirty-six stars—one for each State in the Union.

In Baltimore there would be no official ceremonies, sermons, or speeches; there was no time for that. Instead, as soon as Lincoln’s coffin was in position, and after the military officers and dignitaries from the procession enjoyed the privilege of viewing him first, guards threw the doors open and the public mourners filed in. Over the next four hours, thousands viewed the remains. The upper part of the coffin was open to reveal Lincoln’s face and upper chest. Lincoln’s enemies could have masqueraded as mourners and come to gloat over his murder, but the crowd would have torn them to pieces.

In Baltimore, Edward Townsend established two rules that became fixed for every stop during the thirteen-day journey. “No bearers, except the veteran guard, were ever suffered to handle the president’s coffin,” he declared. Whenever Lincoln’s corpse needed to be removed from the train, loaded or unloaded from a hearse, or placed upon or removed from a ceremonial platform or catafalque, his personal military guard would handle the coffin.

Each city would furnish a local honor guard to accompany

the hearse and to keep order while the public viewed the body, but these men did not lay hands upon the coffin. Townsend also forbade mourners from getting too close to the open coffin, touching the president’s body, kissing him, or placing anything, including flowers, relics, or other tokens, in the coffin. Any person who violated these standards of decency would be seized at once and removed.

At about 2:30 p.m., with thousands of citizens, black and white, still waiting in line to see the president, local officials terminated the viewing, and Lincoln’s bearers closed the coffin and carried it back to the hearse. A second procession delivered the remains to the North Central Railway depot in time for the scheduled 3:00 p.m. departure for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The orderly scene in the Monumental City, as Baltimore was called, was a good omen for the long journey ahead. The first stop had gone well. General Townsend dispatched a telegram to Stanton: “Ceremonies very imposing. Dense crowd lined the streets; chiefly laboring classes, white and black. Perfect order throughout. Many men and women in tears. Arrangements admirable. Start for Harrisburg at 3 p.m.”

T

he train stopped at the Pennsylvania state line, and Governor Andrew Curtin; his staff; U.S. Army general Cadwalader, commander of the military department of Pennsylvania; and assorted officers came aboard. Maryland governor A. W. Bradford received them in the first car. En route to Harrisburg the train stopped briefly at York, where the women of the city had asked permission to lay a wreath of flowers upon Lincoln’s coffin. Townsend could not allow dozens of emotional mourners to wander around inside the train and hover about the coffin. He offered a compromise: He would permit a delegation of six women to come aboard and deposit the wreath. While a band played a dirge and bells tolled, they approached the funeral car in a ceremonial procession, stepped inside, and laid their

large wreath consisting of a circle of roses and, at the center, alternating parallel lines of red and white flowers. The women wept bitterly as they left the train. Soon, at the next stop, their choice flowers would be shoved aside in favor of new ones.

The train arrived at Harrisburg at 8:20 p.m. Friday, April 21, and Townsend reported to his boss: “Arrived here safely. Everything goes on well. At York a committee of ladies brought a superb wreath and laid it on the coffin in the car.” Here too, as in Baltimore, no funeral services or orations were on the schedule. To the disappointment of the crowds waiting at the station, a reception for the remains had to be canceled. “A driving rain and the darkness of the evening,” General Townsend noted, “prevented the reception which had been arranged. Slowly through the muddy streets, followed by two of the guard of honor and the faithful sergeants, the hearse wended its way to the Capitol.”

Undeterred by the severity of the storm, thousands of onlookers joined the military escort of 1,500 men who had been standing in the rain for an hour and followed the hearse to the state house. To the boom of cannon firing once a minute, the coffin was carried inside and laid on a catafalque in the hall of the house of representatives. Lincoln was placed on view until midnight. Viewing resumed at 7:00 a.m. on Saturday. For the next two hours, double lines of mourners streamed through the rotunda. The coffin was closed at 9:00 a.m., and at 10:00 a.m. a procession began to escort the hearse back to the railroad depot. This became the grand march the public had hoped to witness the previous night.

A military formation led the way. Then came the hearse, accompanied by the guard of honor from the train plus sixteen local, honorary pallbearers. There followed a cavalcade of passengers from the funeral train, including the governor of Pennsylvania, various generals and officers, elected officials, fire and hook and ladder companies, and various fraternal groups including Freemasons and Odd Fellows.

O

n April 22, Jefferson Davis was still in Charlotte. Lincoln’s murder had put his life in great danger, but he still considered the cause more important than personal safety. Indeed, the idea of “escape” was anathema to him. In his mind, he was still engaged in a strategic retreat, not a personal flight.

Davis was not alone in his desire to continue the fight. Wade Hampton wrote to him again from Greensborough and encouraged him to make a run for Texas. “If you should propose to cross the Mississippi River I can bring many good men to escort you over. My men are in hand and ready to follow me anywhere…I write hurriedly, as the messenger is about to leave. If I can serve you or my country by any further fighting you have only to tell me so. My plan is to collect all the men who will stick to their colors, and to get to Texas.”

Varina Davis, safe in Abbeville, South Carolina, wondered where her husband was. On April 22 she wrote to him via courier that she had not received any communication from him since April 6, when he was still in Danville, Virginia. “[I] wait for suggestions or directions…Nothing from you since the 6th…the anxiety here intense rumors dreadful & the means of ascertaining the truth very small send me something by telegraph…the family are terribly anxious. God bless you. Do not expose yourself.”

T

he funeral train was scheduled to leave Harrisburg at noon on April 22, but the hearse arrived at the station almost an hour early. General Townsend telegraphed Stanton from the train depot shortly before pulling out: “We start at 11.15 [a.m.] by agreement of State authorities. It rained in torrents last night, which greatly interfered with the procession, but all is safe now.”

On the way from Harrisburg and Philadelphia, the train passed through Middletown, Elizabethtown, Mount Joy, Landisville, and Dillersville. At Lancaster twenty thousand people, including Con

gressman Thaddeus Stevens and Lincoln’s predecessor, former president James Buchanan, paid tribute. The train pushed north through Penningtonville, Parkesburg, Coatesville, Gallagherville, Downington, Oakland, and West Chester. At every depot, and along the railroad tracks between them, people gathered to watch the train pass by. For miles before Philadelphia, unbroken lines of people stood along both sides of the tracks and watched as the train went by them.

When the train arrived at Broad Street Station in Philadelphia at 5:00 p.m. on Saturday, April 22, it was greeted by an immense crowd. The

Philadelphia Inquirer

explained the reason: “No mere love of excitement, no idle curiosity to witness a splendid pageant, but a feeling far deeper, more earnest, and founded in infinitely nobler sentiments, must have inspired that throng which, like the multitudinous waves of the swelling sea, surged along our streets from every quarter of the city, gathering in a dense, impenetrable mass along the route…for the procession.”

A military escort, including three infantry regiments, two artillery batteries, and a cavalry troop, had arrived at the depot by 4:00 p.m. in preparation. A vast crowd had assembled along the parade route, and as soon as the engine rolled into the depot, a single cannon shot announced to the city that Lincoln had arrived. Minute guns began to fire.

At 5:15 p.m. the hearse, drawn by eight black horses, got under way. With the military escort leading the way, the huge procession took almost three hours to reach the Walnut Street entrance on the southern side of Independence Square. There, members of the Union League Association had assembled to receive the coffin and guide its bearers to the catafalque inside Independence Hall. According to one account, “the Square was brilliantly illuminated with Calcium Lights, about sixty in number, composed of red, white and blue colors, which gave a peculiar and striking effect to the melancholy spectacle.”

As minute guns continued firing and the bells of Philadelphia tolled, Lincoln’s body was carried into the sacred hall of the American