Bloody Crimes (51 page)

THE TWILIGHT YEARS AT

BEAUVOIR.

raised more medicine to his lips, he declined: “I pray I cannot take it.” He fell asleep, and shortly after midnight, on December 6, 1889, he died peacefully in his bed, his wife’s hands folded into his.

It was nothing like the death of Abraham Lincoln, which was unexpected, sudden, violent, bloody, and when he was in his prime. Neither Lincoln, nor his family, nor the people had time to prepare for it. Lincoln had no time to say good-bye. He enjoyed no final, long look back to recall his life and tally his deeds. Jefferson Davis was granted this privilege. He enjoyed the gift of years to live, to write, and to reflect. He had fallen and yet lived long enough to rise again. And the people of the South had nearly a quarter of a century to prepare themselves for his death. Davis had the chance to review his life in full, and to retrace his journey to the beginning.

For Lincoln, the end was only darkness. But in one way their deaths were the same. Just as April 15, 1865, symbolized to the North more than the death of just one man, so too the death pageant that followed December 6, 1889, was not for Davis alone.

JEFFERSON DAVIS IN DEATH, NEW ORLEANS, DECEMBER 1889.

JEFFERSON DAVIS LIES IN STATE IN NEW ORLEANS.

After Davis was embalmed, while he lay in state, a photographer set up his camera and lights to take pictures of the corpse. But there would be no repeat of the scandal that had occurred after Lincoln’s remains had been photographed in New York City in April 1865. Varina had given permission for one photographer to make several dignified images of her husband’s body, and she allowed at least one print to appear in a memorial tribute volume published by a trusted friend and longtime supporter, the Reverend J. William Jones. These photos of Davis’s corpse, taken much closer to the body, and offering far greater detail than Gurney’s images of Lincoln, captured Davis in elegant repose, dressed in the coat of Confederate gray that Jubal Early had given him, and clasping in his folded hands sheaves of Southern wheat. His lips formed a faint, subtle smile. Varina also consented to a death mask, an application of wet plaster to the deceased’s face that would result in a perfect, life-size, three-dimensional likeness of Davis’s visage. Edwin M. Stanton had not allowed a death mask of

Abraham Lincoln—it was too morbid and disrespectful, he might have reasoned. For Davis, it would be a necessary artifact for the many monuments his supporters intended to build in his honor. Lincoln’s two life masks, made in 1860 and 1865, had proven priceless for this purpose. So too would Davis’s death mask.

In Washington, the government of the United States took no official notice of the death of Jefferson Davis. The mayor of New Orleans had sent a clever telegram notifying the War Department of the death of, not the former president of the Confederate States of America, but of a former secretary of war of the United States. Protocol dictated that the department fly its flag at half-staff and close for business. But Secretary of War Proctor declined to recognize the passing of

Davis, and he refused to lower the American flag. If federal authorities refused to take notice of the death of the former cabinet officer, that did not deter at least one sympathetic private citizen in the nation’s capital from mourning the Confederate president. On Capitol Hill, across the street from the Watterston House, home of the third librarian of Congress, and a local landmark visited by Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and other luminaries, blatant symbols of mourning adorned a town house, causing a local sensation. The

Washington Post

reported the unusual occurrence:

A STRIP OF BLACK CLOTH. A Washington Lady Shows Her Grief at Jeff. Davis’ Death. Probably the only outward evidence of sympathy for “the lost cause” and tribute to the memory of Jefferson Davis to be seen in this District is to be found at No. 235 Second Street southeast, occupied by Mrs. Fairfax. The shutters of the house are all closed and the slats tightly drawn while running across the entire front of the house, between the windows of the first and second floor, is a broad strip of black cloth looped up with three rosettes—red, white, and red. Mrs. Fairfax is known to have been an ardent supporter of the Confederate cause, and married State Senator Fairfax, of Fairfax County, Va. During the war of the rebellion she gave all the assistance to the South possible, and repeatedly crossed the lines, carrying to the Confederates both information and substantial assistance. It was through knowledge obtained by such expeditions as this that leaders of the Confederate side were enabled to anticipate movements of the Union armies and in a number of instances checkmate them. The house on Second street yesterday attracted more attention, probably, than ever before, and the emblems of mourning were the cause of considerable comment among the neighbors and travelers on that street.

In Alexandria, Virginia, where George Washington had kept a town house, where slave pens and markets once flourished, where Colonel Elmer Ellsworth was killed twenty-eight years ago, and where Lincoln’s funeral car was built in the car shops of the United States Military Railroad, the sounds of mourning rose above the city and echoed over the national capital. Old Washingtonians remembered when the bells had tolled for Lincoln. Now they heard them toll for Jefferson Davis.

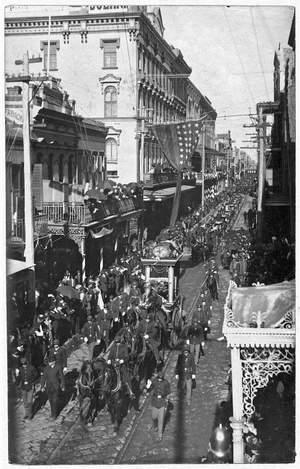

There was a magnificent funeral in New Orleans, a huge procession just like the one in Washington for Lincoln, and Davis was interred at Metairie Cemetery. But on the day Davis was buried, everyone knew this was only a temporary resting place. It was understood that Varina Davis would in due course select a permanent gravesite elsewhere. Several states, including Mississippi, vied for the honor. In 1891, Varina stunned Davis’s home state. She vetoed its proposal and chose Virginia. Davis would return to his capital city, Richmond.

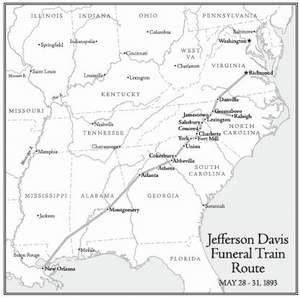

On May 27, 1893, almost three and a half years since Davis’s death, his remains were removed from the mausoleum at Metairie Cemetery. A hearse carried his coffin to Camp Street, to Confederate Memorial Hall, a museum crammed with oak and glass display cases filled with Civil War guns, swords, flags and relics. From 5:00

P.M.

on the twenty-seventh until the next afternoon, Davis lie there in state. Then a procession escorted his body to the railroad station, where it was placed aboard the train that would take him to Richmond. Like Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train, the one for Jefferson Davis that left New Orleans on May 28 did not rush nonstop to its destination. First it paused at Beauvoir, where waiting children heaped flowers upon the casket. The train stopped briefly at Mobile shortly after midnight on May 29 to change locomotives, then stopped at Greenville, Alabama, at 6:00

A.M.

People lined the tracks, and wherever the train halted, mourners filled Davis’s railroad car with flowers.

Arriving in Montgomery during heavy rains early on the morning of May 29, the train was met by fifteen thousand people. For the

first time since Davis’s remains left New Orleans, they were removed from the train. A procession escorted the hearse to the old capitol, where in 1886 he experienced his great resurrection. While Davis lie in state in the chamber of the Alabama supreme court, bells tolled and artillery boomed. A large banner reminded mourners that “He Suffered for Us.” To anyone who remembered the Lincoln funeral cortege, the sight of another presidential train winding its way through the nation, its passage marked by crowds and banners, and by the scent gunpowder and flowers, the experience was familiar and eerie. Floral arches erected in towns along the route of Davis’s final journey proclaimed “He lives in the Hearts of his People.” Once, identical words greeted Lincoln’s train.

Davis’s train reached Atlanta at 3:00

P.M.

on May 29, and forty thousand people passed by his coffin. The train pushed on through Gainesville, Georgia; Greenville, South Carolina; and then into North Carolina, where it passed through Charlotte, Salisbury, Greensboro, and Durham. All along the way, people built bonfires, carried torches, rang bells, and fired guns to honor the esteemed corpse. At Raleigh, the coffin was removed again, placed in a hearse, and paraded through town. After lying in state there, Davis was taken to Danville, Virginia, his first refuge after he left Richmond the night of April 2, 1865.

The funeral train arrived in Richmond at 3:00

A.M.

on May 31. In the middle of the night, a silent procession escorted the coffin from the station to the state capitol. Artillery fire woke the city later that morning, and twenty-five thousand people, including six thousand children, passed by his casket. At 3:30

P.M.

a grand procession escorted his remain to Hollywood Cemetery. There, a simple gravesite ceremony and a bugle playing taps ended his last journey.

In preparation for this day, word was sent to Washington, D.C., to Oak Hill Cemetery, where workers opened a small grave that had gone undisturbed since 1854, almost forty years before. The body of Samuel Davis was brought to Richmond to rest by his father. And

THE NEW ORLEANS FUNERAL PROCESSION.