Boost Your Brain (37 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

Despite the brain’s recovery efforts, though, the cascade often ends in brain atrophy, most obviously in the brain areas surrounding the injury but also in the hippocampus. In fact, seven studies conducted between 1997 and 2009 found a smaller hippocampus size in people who’d suffered either acute or chronic traumatic brain injury.

3

In my own review of the literature I was struck anew by the vulnerability of the hippocampus: even though the hippocampus doesn’t take a direct hit, it is so sensitive that it shrinks, sometimes even more so than the areas that got bruised in the initial impact.

4

Changes to the hippocampus can continue three to seven months after a TBI and are associated with cognitive decline. Even in children, who are blessed with a neuroplasticity that helps offset trauma, hippocampal shrinkage can persist later in life.

5

Not surprisingly, given the havoc it wreaks, TBI significantly hampers healthy brain activity, which can persist long term if the injury is severe enough. In EEG brain maps of TBI patients I often see increased delta and theta activity in the frontal lobes—or “too much tuba.” TBI patients also have low alpha and sometimes too much high beta activity as well. Depending on the level of injury, the “sounds” their orchestras produce may be anywhere from slightly off tempo to wildly chaotic.

Abnormal brain activity from TBI is so apparent, in fact, that a new, portable EEG device has been developed to help detect TBIs outside of a medical facility, be it on a football field, a battlefield, or anywhere else concussions are likely to occur. That device, called BrainScope, is now in clinical trial. Initial small trials showed that the handheld device can detect abnormal EEG patterns following a blow to the head, suggesting it may one day prove a valuable tool for coaches, parents, players, and soldiers.

Hard to Think

While it might seem obvious that injuries like Gary’s would produce lasting cognitive problems, I often find patients are surprised to hear that brain injuries earlier in life may be contributing to their poor memories, confused thinking, or difficulty functioning in midlife. Even seemingly less severe, one-time events can cause headaches, balance issues, vision problems, ringing in the ears, and other physical problems that persist long past the injury. TBIs can also trigger mood disorders, such as depression, irritability, and anxiety, among other things.

Clearly major TBIs associated with a loss of consciousness shrink the brain—so much so that the effect can be seen on MRI. But even TBIs without noticeable symptoms can inflict microscopic damage that erodes brain reserve. Such “silent hits” may not result in a concussion diagnosis but may still affect brain function.

In one study, for example, a team of University of Illinois researchers had ninety college students perform cognitive tasks while undergoing EEG. Those who’d suffered concussions had slower electrical activity in their brains than those who hadn’t suffered TBIs.

6

This, despite the fact that the injuries had occurred, on average, more than three years earlier and the students appeared outwardly to have no lasting effects from their injuries. In another study, students who’d had TBIs also showed slightly abnormal results on a test of balance, a finding that’s often seen in the elderly at risk for falls.

7

Other researchers have also put forth compelling evidence that multiple small injuries add up in the brain. While one big hit can create a major concussion, the damage from repeated minor traumas to the head can actually accumulate over time until a tipping point is reached, with the next small hit resulting in a sharp cognitive decline. In one study, for example, researchers at Purdue University looked at forty-five high school football players over two playing seasons.

8

Conducting cognitive testing and fMRIs, the researchers found that even silent hits caused changes in the brain, without causing noticeable symptoms. Brain reserve likely provided a cushion that allowed these young people to sustain damage to their neurons and highways and still function well. But brain reserve can eventually run low. It’s not unlike the brake pads on your car: they’re designed to cushion your brakes, but eventually, with enough mileage or strenuous use, they wear out.

At that point, damage can have far-reaching effects. As Gary discovered (and as researchers have demonstrated), injuries to the frontal lobes can cause damage that actually contributes to the likelihood of sustaining future head trauma. Even temporary symptoms can have an effect that might lead to another injury. A football player with a mild concussion, for example, might experience an almost imperceptible reduction in his reaction time while concussed, making him more likely to take a second hit.

Even those who don’t suffer another injury immediately are more likely to suffer future concussions. In one study, researchers followed 2,905 football players from twenty-five colleges and found that those who’d had a concussion were four to five times more likely to suffer another concussion in the future.

9

There’s evidence, too, that recovery may be slower on subsequent concussions compared to the first.

Concussions also appear to increase the risk of dementia later in life. In 2010, a study of retired professional football players, for example, found that players who’d had three or more concussions were five times more likely to have cognitive impairment late in life than those without concussions.

10

Another study found that losing consciousness for more than thirty minutes increases your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

11

What’s interesting about this is that a severe concussion—or repeated smaller hits—results in the immediate formation of the very tau tangles (and even amyloid plaques) that we see in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Autopsy examination of young people who have died soon after TBIs shows a striking finding—despite their youth, their brains accumulated Alzheimer’s pathology, both at the site of the brain contusion and in the hippocampus. This pathological finding, along with shear injuries to the fiber bundles and overall brain atrophy, explains why TBI patients can’t think straight for years after their injuries.

One new brain imaging technique (FDDNP) that shows the presence of plaques and tangles in living patients with Alzheimer’s disease has detected the very same lesions in young NFL players who’ve had concussions.

12

The devastating formation of Alzheimer’s pathology followed by significant impairments years or decades later is called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). This condition has been documented in boxers, military blast victims, and football players.

13

Sufferers of CTE experience brain damage that results in memory loss, confusion, depression, and aggression often years after the injuries are sustained.

Perhaps most alarming of all is evidence that the damage may begin to accumulate far sooner than was once thought and even in the absence of serious TBIs. It’s a possibility not yet proven but certainly suggested by what scientists found when they examined the brain of twenty-one-year-old college football player Owen Thomas, who committed suicide in 2010.

14

Multiple “silent hits,” multiple concussions (with or without immediate symptoms), and more severe TBIs all are associated with brain atrophy. While the brain recovers from a few minor hits, the more frequent and the more severe the TBIs, the more your brain will shrink.

Though Thomas had been a lineman, a punishing position that involves taking countless hits, he’d never had a documented concussion. The death of the once-happy, popular player was so inexplicable that his family agreed to donate his brain to the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University’s School of Medicine in the hopes a closer look would offer answers.

What scientists found was shocking. Despite Thomas’s young age and his lack of any serious head injuries, his brain showed the early signs of CTE.

Who Gets Hurt

Football gets a lot of attention for its head-damaging potential, but it’s not the most common cause of TBI. The majority of TBIs, instead, come from car accidents or falls.

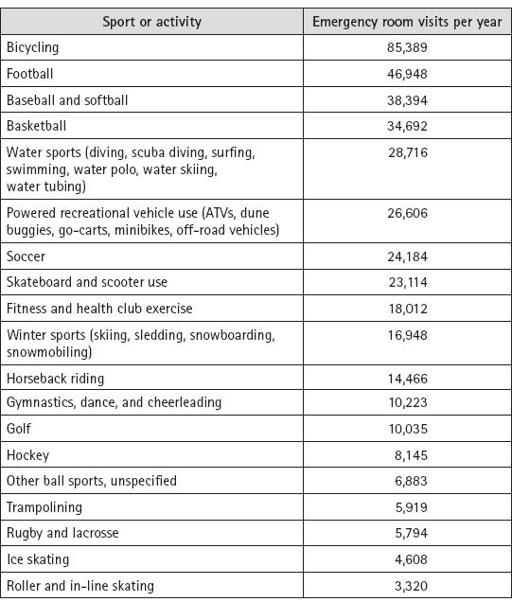

Still, many sports and recreational activities carry risks for TBI, at any age. Here are the top nineteen sports and recreational activities that contributed to head injuries in 2009, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons:

15

Getting Back in the Game?

There is no exact science behind how long it takes a bruised brain to heal completely. Part of the reason is that it’s currently impossible to see microscopic damage that may have been done by a hit to the head.

For now, doctors rely on time and observation to tell them how well someone is healing. And until science comes up with a better way to measure how the brain is healing, it’s best to tread with caution. Athletes with a suspected concussion, for example, should be taken out of play and shouldn’t return until all symptoms have disappeared completely. Of course, this assumes that you have a diagnosed TBI. Oftentimes people don’t actually get to that point because they brush off their symptoms or don’t make the connection between their headaches and the hard knock they took, say, playing hockey the week before.

You can help minimize damage from a TBI by:

• seeking medical attention when a concussion or more serious TBI is suspected,

• following your doctor’s orders for mental and physical rest following a TBI, and

• seeking out a specialist if problems persist.

Preventing Trauma

As someone who deals every day with people who’ve been laid low by traumatic brain injury, I have to admit that I’ve become pretty vocal about educating others on the importance of protecting the brain.

In many ways that’s become easier, thanks to technologies like advanced safety devices in cars; seat belts and car seats for children; a more consistent use of helmets when biking, skating, skiing, or snowboarding; and a growing public understanding of the dangers of head injuries. In recent years coaches, parents, and doctors have begun to advocate for more protection for kids playing sports. New helmets offer better cushioning for the head, and safety-minded rules prevent some of the more dangerous moves in sports such as football. I’m hopeful that better awareness about concussion also means athletes of all ages will give themselves time to heal after a concussion before returning to play.