Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (14 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

In reality I could clap.

I went to all the band practices, although mostly I just stood there. The name of this band was Mock Combo, and they played popular Western music, from Elvis Presley to the Beatles, as well as American country songs like “Red River Valley.” We had no idea where Red River Valley was, just somewhere in the Old West.

Amita and I also bonded over table tennis. I was quite skilled at the game—but so was she. Table tennis, or Ping-Pong as Americans call it, is very popular in India. Amita’s younger sister was going out with the junior national champion, so Amita had played a lot. In Amita’s home they had set up a net across the center of the dining room table. To me this was impressive: She was both a lovely and intelligent young woman and an excellent table tennis player. I asked her to be my mixed-doubles partner in the medical school tournament. She agreed and we won the final decisively.

In India at that time young people didn’t generally go out on dates. Instead, we went out as a group. Often Amita and I would go to dinner with her two sisters and even her mother, which was quite normal back then. But eventually I knew it was time for more. I approached Amita.

“I want to take you out for a date,” I said. She asked me what I wanted to do. “Dinner and a movie.” She asked me what movie I wanted to see. (She wasn’t making this easy.) “It should be a surprise,”

I said. And so we went to see

Dr. Zhivago,

which I had already seen and loved.

Gradually we got to know each other. Amita loved India, so much that she had wanted to join the Foreign Service and travel the world educating people about our country and its values. In school she had studied economics, but after being persuaded to go into medicine, she took her premed courses.

Amita, I learned, was a much more spiritual person than I was. Her father had been an engineer for the Central Public Works Department, constructing roads and bridges, alternating between urban and remote areas of the country. As with my family, every two or three years the government would send them to another post. Although her father was a very practical man, every morning he would sit cross-legged in a lotus position on a deerskin rug, reading the Bhagavad Gita and meditating. He practiced a type of yogic meditation. Eventually Amita, too, would close her eyes and sit quietly in that lotus position. She didn’t know what she was doing, she told me, but even from that tender age she yearned for spiritual experiences.

By the time we were ready to graduate we had decided to marry. While arranged marriages were still quite common in India, we had found each other and fallen in love. We prided ourselves on being modern Indians. I went to my parents and told them that we had decided to have a civil ceremony rather than the traditional large wedding.

My mother, obviously, was very disappointed.

“It’s not for me,” she said, “but for your grandfather. He’ll be very sad that you’re not following the ancient traditions.”

“Don’t worry, Mom,” I said. “I’ll talk to him.” I spoke with my grandfather and promised him that we would do things right. Typically, in Indian weddings, several hundreds of people are invited to the reception. I told him that we were going to have a large reception at the fancy Delhi Gymkhana Club, one of India’s oldest clubs, and that our marriage would be blessed by a priest. This was sufficient for him; he just wanted us to be happy.

Everything was set. But when Amita and I went to court to get

a marriage license we were informed that we were too young. We learned that you had to be twenty-one to have a civil marriage in India. So I went back to my parents.

“We’ve changed our minds,” I announced. “We’re going to have a traditional Hindu wedding.” In preparation my father and I sat down with the priest who would officiate. We wanted to be married on a certain date, so the priest looked at the star charts and told us that the date was not auspicious. My dad, being a modern physician, slipped the priest a couple of hundred rupees and asked him to take another look. The priest suddenly exclaimed that a planet was in a different position than he had originally thought and that the date my father had suggested was indeed very auspicious.

As the priest was leaving, I walked outside with him to his scooter. Hindu ceremonies can sometimes go on for hours; it’s completely up to the officiant.

“Listen,” I said. “Don’t go on too long. If you keep the ceremony short, there’s another bonus in it for you.”

We had a lovely, brief, traditional Hindu marriage ceremony and set off to live a modern life. I had certainly gotten much more than I had bargained for out of medical school.

As I write this I’m reflecting on how fortunate I am to be married to Amita, a beautiful lady, a brilliant pediatrician, a very spiritual being, and a kindred soul for more than four decades.

9

..............

Innocent Bystander

Deepak

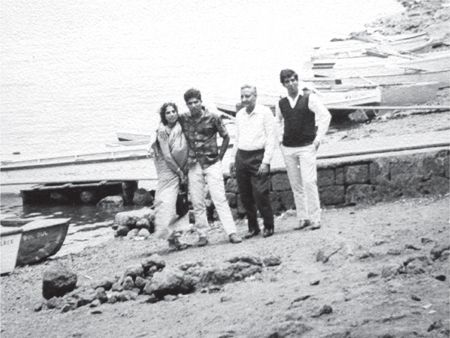

Chopra brothers with their parents, lakeside, on a trip to Mahabaleshwar, 1967.

I

HAVEN’T MENTIONED HOW DEEPLY

my father’s patients affected me when I was growing up, largely because they didn’t. A constant stream of sick people came through our house during the Jabalpur years. Many were desperate and broken, bewildered by their illness due to a complete ignorance of medicine. They made a pitiful sight, but my world was preoccupied with two obsessions that blocked them out: I was obsessed during school hours with study, and I unwound by obsessing over cricket the rest of the time. In Shillong, Sanjiv and I would run down the hill to a kiosk in the teeming bazaar that sold

Sport and Pastime

magazine. It had the latest news and pictures of our heroes in action. These we tore out to paste in our scrapbooks. Two early obsessions might have shaped my life but for the fact that a self is built from invisible bricks as well as the ones that show in the facade.

My father wanted me to become a doctor, but I don’t remember his expressing disappointment when I set my sights on journalism instead. He didn’t believe in interfering and put his faith in being a quiet influence. When he and my mother discussed his cases every evening, I wasn’t coaxed to join in. His decisive move was much more subtle. One birthday my present was a set of popular novels. I wasn’t aware that this was an act of insidious propaganda. But all three books featured doctors as their heroes, each hero deeply immersed in adventure, melodrama, and affairs of the heart. It was easy to believe that examining a pathology slide under the microscope was inches away from falling desperately in love or, second best, saving the world. (Since the plots are engraved in my memory, I’ll mention that the three novels were

Of Human Bondage, Arrowsmith,

and

Magnificent Obsession.

) Reading fiction, it was possible to feel that medicine was romantic and sometimes tragic. At home my father was a constant presence, so it didn’t occur to me that he had risen

from nothing like Sinclair Lewis’s Martin Arrowsmith and was as brilliantly skilled as Robert Merrick, the surgeon hero in

Magnificent Obsession.

Something in me changed. The spell woven in those books lured me away from journalism, despite the fact that at sixteen I would eagerly have modeled my life on Rattan Chacha. My parents were overjoyed when I announced my decision to study medicine, but it posed a sizable practical problem. I was due to graduate from St. Columba’s in December 1962 without any credits in biology, and without biology you couldn’t get into medical school. The system had a loophole, however. I was on an educational track that mimicked English schooling so closely that our final exams, after finishing the grade known as 11 Standard, were O Levels set by Cambridge University. The exams were shipped over from England and then returned to Cambridge to be graded by hand. This cumbersome process took seven months before I would know if I had passed with honors.

In the meantime, from December to the following July, I was privately tutored in biology by a Bengali who came to the house every day and rushed me through the basics. I would then take a year of premed in Jabalpur at the college level. After that I could apply to medical school. When it came time to dissect a frog, my tutor and I went down to a pond and caught the frogs ourselves (this was India). He showed me a trick—sneak up on the frog from behind and with one swift motion pinch its spine, rendering it immobile.

Back home we pithed the specimen, which involved sticking a needle at the junction point between the skull and the spine. This paralyzed the frog while keeping it alive (it also blocked any pain). If you are suited to becoming a doctor, the first moment you open up a living creature is fascinating, as you set eyes on a beating heart and can view under a microscope the red blood corpuscles squeezing in single file through semitransparent capillaries. The squeamish quickly turn away. As the seven months wore on, I had to memorize hundreds of taxonomic facts, giving me general knowledge about classifying plants and animals in Latin that was totally useless to a doctor. But filling a storehouse of nickel knowledge served me in a

peculiar and satisfying way. In effect, I pithed my emotions by sticking a needle at the junction point where the brain meets the heart.

Medical training winnows out a portion of human nature, especially the emotions. This is deliberate. A doctor is a technician whose task is to spot defects and injuries in the human body. He relates to it as a garage mechanic relates to a damaged automobile. Both run body shops. The more efficient the interaction between doctor and patient, the better. Tears and distress are irrelevant, even if they are all too human. In my father’s practice, his patients had not grasped how to play their part with efficiency. They were like car owners who accost a mechanic with statements like “I love my Subaru so much, it breaks my heart to see it like this” rather than “The steering feels a little loose.” My father was also inefficient. He empathized with his patients’ distress instead of blocking it out so that he could impersonally assess which parts were broken—and there were literally thousands of parts to consider, down to the most microscopic detail. (In fairness, my father always warned us not to form an emotional attachment with patients, advice he routinely ignored himself.)

I’m exaggerating the contrast because my inclination was toward the scientific and impersonal from a very early stage. I was nothing if not a professional student. I could memorize reams of facts. I saw, too, that if you didn’t want to be left behind, you woke up to the bald fact that medicine

is

science. My father was just at the cusp of this realization, which may seem strange since Louis Pasteur had established the germ theory of disease in the 1850s. But practice didn’t keep up with theory. In

The Youngest Science,

Lewis Thomas’s memoir of three generations of doctors, he points out the futility of medicine well into the twentieth century.

A doctor’s traditional role was to comfort far more than to heal. He sat at his patient’s bedside dispensing hope and a generous supply of patent medicines that were nostrums at best. At worst they were vehicles for substances like laudanum, a narcotic so liberally prescribed that it turned countless Victorian women, who believed in taking a spoonful of tonic a day, into hopeless addicts. Childhood illnesses like rheumatic fever left damage that lasted for life. Survival

depended on the patient’s immune system, not on anything the doctor could do. As for adult afflictions like cancer, stroke, heart attacks, and infected wounds, these were invariably fatal. Lewis points out that his father, a skilled physician, didn’t routinely cure anyone until the discovery of penicillin in 1928. The wholesale marketing of drugs like streptomycin, the first antibiotic to treat the scourge of tuberculosis, didn’t come about until the late Forties (not early enough in widespread use to save the life of George Orwell, who died of TB in 1950, much less D. H. Lawrence, who succumbed to it in 1930. Both were in their forties).

My father joined the great wave of scientific medicine as it arrived in India, which was the main fact that I absorbed. But I missed something important—maybe the most important thing of all—that was wrapped up in a wartime anecdote. He rarely spoke about his experiences in World War II, and most people have forgotten, if they ever knew, that the Japanese did invade India, marching up from Burma into the far northeast state of Manipur. There the Battle of Kohima took place, a grueling three-month siege in 1944 that became a turning point in the war. Kohima was later called the Stalingrad of the war in Asia, after the deadly winter siege in Russia.

Serving as a medical officer, my father encountered suffering that he never wanted to talk about. In that he was like many veterans after they came home. But one patient stuck in his mind, a private who overnight became unable to speak. It was assumed that he had suffered a stroke; aphasia—the loss of speech—results when a specific region of the brain, Broca’s area, has been damaged. My father examined the young soldier and agreed with the diagnosis. But one day some new facts emerged.