Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (5 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

In a village in the foothills of the Himalayas, there was one family that had refused the smallpox vaccine. The Indian government and World Health Organization had successfully vaccinated the rest of the population, but the head of this family, Mr. Laxman Singh, steadfastly refused. The Indian government decided for the good of the country that the Singhs had to be protected against this terrible disease, so they sent a medical team and law enforcement to their house.

“Why won’t you be inoculated?” Laxman Singh was asked.

“God ordains who will be diseased and who will be healthy,” he responded. “I don’t want this injection. If I have to get smallpox, I’ll get smallpox.”

The team restrained him, forcibly pinning him to the ground. Singh fought them while screaming bloody murder, but they successfully inoculated him and then did the same to the rest of his family. When this was finally done, Laxman Singh calmly said, “Now please sit down in my hut.” He went to his plot, picked some vegetables, cleaned them, and served them to the medical team along with some fresh tea his wife had made.

“What are you doing?” one team member asked. “We came into your house, violated your beliefs, and now you’re treating us as guests. Why?”

“I believe it is my dharma to not get inoculated because God ordains who will be diseased and who will be healthy. You obviously believe it is your dharma to inoculate me. Now it is over and you are guests in my home. This is the least I can offer you.”

This story is the best demonstration of dharma I have found. For me the word “dharma” incorporates the elements of duty, creed, and ethics. As a child I certainly never suspected that my dharma would bring me to America and Harvard Medical School, but I followed the path that was laid in front of me. My family’s roots in the Indian soil can be traced back centuries; planting new ones in another part of the world was never part of my plan. But the actions of fulfilling my dharma have brought me honors in my profession and in my life. As a result, I embrace both Eastern and Western traditions. I speak American slang with an Indian accent. I’ve spent my life in medicine, relying on the tools of science—experimentation, discovery, testing, and reproducible results—but being brought up in my culture also left me open to other possibilities, ones that might not be scientifically proven or easily understood. I am privileged to lecture annually to as many as fifty thousand medical professionals in the United States and around the world, and each time I do so I feel I am fulfilling my dharma.

When my parents first traveled from Bombay to London, it took them about three weeks by ocean liner. Now I can get on an airplane in Boston and be anywhere in India in less than a day. When I’m there, walking the streets of what is now Mumbai, I see many of the same international chain stores that I’d passed hours earlier in Boston. Growing up, we didn’t have television, but now I can turn on the set in India and watch some of the same shows I enjoy in the United States. Once, the only news we got was from All India Radio or the BBC. Now I can simply log onto Twitter, where I follow CNN, NBC, and the

New York Times,

instantly receiving the latest

news from around the world. Because of advances in travel, communications, entertainment, and business, the world has gotten much smaller; the once distinct cultures of the world are blending, perhaps too much. But I’ve always found great comfort knowing that the core values I was taught by my family as part of our Indian culture still make an impact. They have allowed me to become a successful husband, father, grandfather, physician, and lecturer, in America.

3

..............

Charmed Circle

Deepak

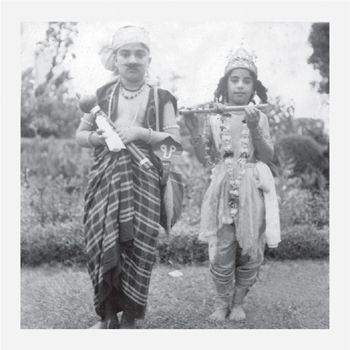

Deepak and Sanjiv win first and second prize at a fancy-dress competition, as a snake charmer and as Lord Krishna, Jabalpur, 1958.

I

MUST HAVE BEEN ABOUT THREE

and a half when my earliest memories were formed. Being frightened and abandoned sticks in the mind. I was sitting alone in a city park, guarded by a magic circle drawn around me in the dirt. I watched the trees, not yet terrified, even though it was certain that, if I crept outside the circle, demons were waiting in the shadows.

The family had hired an

ayah,

or nanny, to look after me and my infant brother, Sanjiv. One of her duties was to take us to the park every afternoon so that my mother could have a few moments of peace. Was our ayah named Mary? Names are easily lost, but not feelings. In Pune, where my father was stationed (he hadn’t yet traveled to London for advanced training in cardiology), the ayahs were often young girls from Goa, a part of India settled by the Portuguese, where Christianity strongly took hold.

Whomever she was, our ayah kept looking over her shoulder every time we arrived at the park. At a certain point she would plunk me down on the ground and draw a circle around me in the dirt. She would warn me not to stray—outside the circle were demons—and then disappear. With or without Sanjiv’s baby carriage? That detail is lost. Half an hour later Mary would return, looking flushed and happy. Then she would take us home, reminding me to say nothing about her vanishing act. It would be our little secret. It was several years before I pieced together what was really going on.

First, the circle and the demons lurking outside it. Mary picked this up from a mythic story. By the time I was five or six, my mother began telling me tales from the two treasure troves of stories in Indian scriptures. One is the Mahabharata (

Maha

means great, and

Bharata

is the Sanskrit name for India), an epic saga of a war for succession in the ancient kingdom of Kuru. Its immortal centerpiece is the section

known as the Song of the Lord, the Bhagavad Gita. If India is the most God-soaked culture on earth, it is also Gita-soaked. From childhood one hears verses taken from the conversation between Lord Krishna and the warrior Arjuna as they wait in Arjuna’s war chariot for the climactic battle to begin. The Gita is a cross between the Trojan War and the New Testament, if one had to give a thumbnail description. When Krishna tells Arjuna the meaning of life, he speaks as God made flesh.

But my mother was keen on the other primary collection of stories, the Ramayana, also an epic that involves a battle, this time between Lord Rama, a handsome prince who is an incarnation of Vishnu, and Ravana, king of the demons. Any boy would be transfixed by Lord Rama’s adventures. He was a great archer and had a devoted ally in a flying monkey, Hanuman, whose sole purpose in life was service to Lord Rama.

Blending the human and mythic worlds comes naturally to every child. In my family, though, Rama had a special meaning. Rama was banished into the forest for fourteen years by his father, the king; his father wasn’t angry with him but was forced to keep a promise made to a jealous wife. Leaving tears behind, the prince was followed into exile by his beloved wife, Sita, and, what particularly caught my mother’s attention, his younger brother, Lakshmana.

“You are Rama, and Sanjiv is Lakshmana.”

No sentence was repeated to us more often, although it took awhile before I absorbed its implications: It gave Sanjiv a lower rung on the pecking order than me. Rama was as devoted to his younger brother as Lakshmana was to him. But it was clear who issued the orders and who followed them. This set a selfish precedent in the Chopra family. My mother was adding a religious overtone to our relationship, as a Christian mother might tell her sons, “You are Jesus, and your brother is Simon Peter.”

I felt protective toward Sanjiv, but I didn’t hesitate to play the Rama card when it suited me. One such incident backfired badly. I was ten and the family was living in Jabalpur. My brother and I were in the backyard, practicing with an air rifle; this was a cherished present my

father had brought back with him from London. The target was an empty can sitting on a five-foot post.

A whim entered my head. I stood directly behind the post and told Sanjiv to fire at the can.

He hesitated.

“It’s like William Tell,” I said. “Go ahead. You never miss.”

In school I had just learned the story of William Tell shooting an apple off his son’s head with a crossbow. At the time, standing behind a post while Sanjiv shot an air rifle in my direction seemed pretty much like the same thing. When I finally convinced him to do it, Sanjiv was so nervous he accidentally hit me with a BB right in the chin. It started to bleed, but I was more worried about getting into trouble with our parents than a minor wound.

“We have to lie,” I decided. “I know… let’s go home and say that I fell while climbing a fence. Some barbed wire nicked my chin, that’s all.”

“A lie?” Sanjiv looked distressed. He set his face stubbornly.

“You have to. I’m Rama and you’re Lakshmana.”

Still distressed but less stubborn, Sanjiv reluctantly agreed to go along with my plan, and our parents accepted the concocted story. But my wound refused to heal, and days later when my grandmother felt around my chin, she made a suspicious discovery.

“There’s something in there,” she announced.

A rush to the military hospital revealed the BB lodged in my chin. It was removed without leaving a scar (in family legend, however, this is how I acquired the dimple in my chin). I was sent home with antibiotics and a stern lecture from Daddy about the dangers of tetanus. I was relieved to be caught, actually. This incident was one step in a development that became part of my character growing up: a hesitancy to confront authority. A desire to please my father blended into a stronger desire not to displease him. But I was just at the beginning stages of this trait.

Back to our ayah’s disappearing act. She may have been a Christian, but Mary knew one of the most familiar tales about Lord Rama’s beloved

consort, Sita (the two are a centuries-old model for ideal romance in Indian lore). One day Rama sets out to fetch Sita a magnificent golden deer he glimpsed in the forest. He swears Lakshmana to guard Sita, telling his brother on no account to leave her side.

But when hours pass and Rama has failed to return, Sita begs Lakshmana to search for his brother. Lakshmana is torn. At first he refuses to break his vow, but when Sita accuses him of not loving Rama enough to rescue him from danger, Lakshmana agrees to seek him out. He uses his magical powers to draw a charmed circle around Sita, telling her that she will be safe as long as she never crosses outside the boundary. Any mortal or demon who tries to enter the circle will be instantly consumed in flames. With this, Lakshmana disappears into the forest.

Sita waits anxiously, and the next person she sees is a wandering monk who begs her for alms. He is a pitiful sight, and Sita is too softhearted. She steps outside the circle to put an offering in his begging bowl, and at that instant the monk is transformed, assuming his real identity as the ferocious demon Ravana. He scoops Sita up and abducts her to his island kingdom in the south, beginning yet another adventure in the saga.

My circle in the dirt was more powerful than the one Lakshmana drew; I never dared crawl outside it. But Mary’s mysterious disappearances were for a mundane reason, as it turned out: a secret boyfriend she could only meet in the park when she took her little charges out.

I’m not sorry that she used a myth to train me. The anecdote has an exotic ring, and it fits into a pattern. Flash forward to 1987, at a decisive time when I was coming out of a personal crisis. My frustration with conventional medicine was turning into personal rebellion. A thriving private practice and my position as an attending physician at some prestigious hospitals were at stake. Boston medicine was willing to abandon me if I wanted to abandon it.

I had made my decision to bolt. At the time, people were glued to a sensational television series,

The Power of Myth,

where Bill Moyers was interviewing the eminent authority on world mythology, Joseph

Campbell. I was transfixed. It was like breathing air from a forgotten world. In India taxi drivers create mini shrines inside their cabs to invoke protection, complete with plastic effigies of Ganesha, a beloved god with an elephant’s head and round belly. Their dashboards are plastered with photos of gurus, and long-haul trucks are emblazoned with a slogan invoking Lakshmi, goddess of prosperity:

Jai Mata Di

(Hail Mother Goddess in Punjabi). A new billionaire might place stone statues of various gods and goddesses in the foyer of his multistory mansion before having the interiors decorated by a Parisian designer. The living mythology of modern India provides local color but is also a symbol of deeply felt meaning.

Campbell was a born storyteller who could clothe legends in the fragrant romance they evoked long ago. I remembered that I was once wrapped in mythic ideas—and ideals—that had dropped away like an old skin. Romance wasn’t really the point. Campbell held mythology out as a living presence, the underpinning of everyday life. Unwittingly a businessman waiting on a street corner for the light to change was a hero in disguise. His life had the potential to be a quest. Beneath the mundane details of his days, a vision was crying to be born.