Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (28 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

Not for me, though. Early in my career I had been asked by Dr. Eugene Braunwald, the chairman of the Department of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which is affiliated with Harvard Medical School, to take morning report there. Morning report is an exercise where the interns and residents get together first thing and jot down on a blackboard all the admissions to their service from the previous day. A couple of cases are selected to be discussed as a teaching exercise. Even though I was still based at the West Roxbury VA, I told Dr. Braunwald that I would truly be honored to do so. I started to go to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital on a regular basis and take morning report. I decided to bring with me ultrasounds and CAT scan images of the most interesting patients that I had seen at the West Roxbury VA. I’d present the cases and I would use mnemonics and alliterations to embellish the teaching.

“What do you notice here? Here is calcification of the gallbladder wall. What is this condition called? What is the significance? What

are the other conditions in which there is an inordinately high risk of gallbladder cancer?”

If you loved the mysteries of medicine, these were exciting meetings. The young doctors spoke out, ideas were thrown around—naturally lots of coffee was consumed—and medicine was learned. I would often use repetition; it’s a great tool for adults to remember new facts. I’d repeat what I’d said, then say it again. I took morning report at the Brigham for ten years. During this time I taught but I also learned a lot from my young colleagues. It was a wonderful experience.

There is an annual honor that is given by the house staff at the Brigham called the George W. Thorn Award for Outstanding Contribution to Clinical Education, to honor Brigham’s legendary former chief of medicine, who had an unusually distinguished career and was the personal physician to President John F. Kennedy. It is bestowed on one of the faculty in the Department of Medicine. The medical house staff votes on the award with no input from the chairman or vice chairman of the Department of Medicine. When I started taking morning report there in 1985 I set my goal to win this award someday, although I knew well it had never been given to anyone based outside the Brigham. But I received the award that very first year.

That was also the year that Deepak called one day to tell us that he had decided to close his private practice and begin working at the behest of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi at an Ayurvedic clinic in Lancaster, Massachusetts. I’d thought I knew my brother well, but this decision really surprised me. Deepak had always enjoyed using his intellect to push back the walls, but he had always stayed within the room. This was very different. This was giving up the core of his career: his training as an endocrinologist. It meant giving up science-based medicine to become a practitioner of what many of us believed was folk medicine. It wasn’t my place to discuss this decision with my brother; it was up to him and Rita, and he was firm about it.

By every measure, especially in the quality of patient care, Deepak’s practice was a tremendous success. Medical students from Boston

University and Tufts University School of Medicine rotated through his office, so there certainly was an academic element to his private practice. His life was well established and his family was quite comfortable. This decision would change all of that.

It was a very courageous thing for him to do. By that time Amita and I had been meditating regularly for a couple of years and understood all its benefits. Everyone in TM had emphasized that it should become an integral part of your life, but not your whole life. It seemed like Deepak was making it the centerpiece of his life. But when we discussed it I could see his excitement and his passion. Deepak had always enjoyed finding a new path. I remember thinking of what Emerson once said, “Do not go where the path may lead; go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.” Deepak was truly a trailblazer.

When I responded with some concern in my voice that I was a little nervous about his decision, he said, “I’ll keep my medical license current. That means I can always go back.”

One of my favorite sayings is from the Danish philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard, who wrote, “To dare is to lose one’s footing momentarily. Not to dare is to lose oneself.” I’ve always felt that anyone who takes a bold step to transform their life or undertakes a major challenge or takes a bold step in leadership is incredibly courageous.

And that was the step my brother had decided to take. Of course we all loved him dearly and supported his decision, but I did so with some trepidation.

17

..............

The Pathless Land

Deepak

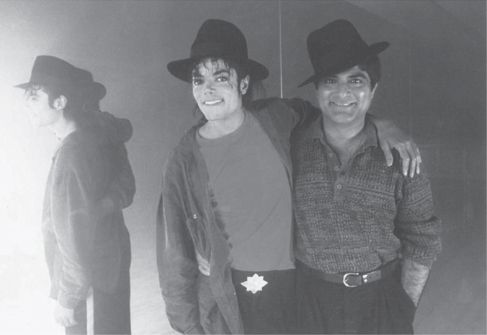

Photo credit by Dilip Mehtra

The Way We Were—

Deepak and Michael Jackson after a dance practice session in Michael’s studio. Deepak showed him a few steps, and Michael couldn’t stop laughing, in the late 1980s.

I

NDIA HAS HAD A ROCKY

road producing messiahs for the West. There’s been a fine line to walk between wisdom and wonders. Some gurus crossed the line willingly. Wonder-working is in the air in India. There is always a saint at the next holy site who can perform miracles, to the point of raising the dead. Some never eat food but live solely on

Prana,

the life force. A great many have the healing touch.

Sadly, when I was growing up, I never met anyone who had actually witnessed a miracle firsthand. My father’s gaze had turned West before I was born. It wasn’t respectable to take wonder-working seriously. Maharishi reached me with a new idea—meditation was a simple, practical technique that changed your consciousness. By this time, however, the West was asking for instant gratification from gurus. A cynical observer dubbed it karma cola.

Rita and I were invited to meet Maharishi in the winter of 1985, so we drove down to Washington, D.C., for a conference that had attracted meditators from all over the country. Maharishi’s visits to the U.S. had become more and more infrequent. By that time we had been meditating for four years. In the most fundamental way I could attest that TM worked. Our more indulgent Indian friends would say, “I’m happy that it works for you.” The implication in “for you” was obvious. They wanted to be left alone. But I was very enthusiastic about this new discovery. The mind did have a level of peace and calm that could easily be reached using the mantra I had been given. I gave up smoking and drinking. My everyday existence was easier and less stressful. Unfortunately one of the reasons that TM had become passé, as far as the marketplace of popular culture was concerned, was that these benefits were no longer flashy enough.

Western disciples wanted miracles from a guru and a facade of Godlike perfection, unblemished by human frailty. The standards

were impossible to reach, and so a backlash had also set in. Partly it was the temptation of excess. The West offered a luxurious lifestyle to a successful guru, along with devotees who would do anything for their master. Some gurus were being accused of sexual impropriety. Their miracles were hyped and then quickly debunked.

I was on a plane seated next to an American couple who were on their way to spend time at their guru’s ashram in south India. At the height of my desire to tell everyone about TM, I held aloof from playing the game of “my guru is better than yours.” But this couple had some amazing tales.

“We have his picture on the mantelpiece,” the husband explained. “We do puja to it every day, and in return things appear.”

“Things?” I asked.

“Mostly holy ash,” he said. Applying a dab of ashes to the forehead of a devotee is a common blessing in India.

“But sometimes we get other things,” the wife added quickly.

“Such as?”

“A gold necklace one time. Another time a gold watch.”

These objects appeared out of the blue, the couple insisted. The messiahs from India were keeping up with their Christian counterpart in the wonders and miracles department, and doing even better, since their miracles might happen in your living room by long distance. A devotee didn’t need to regret that he wasn’t alive two thousand years ago to see Christ walk on the Sea of Galilee.

Nothing uncanny surrounded Maharishi, but our first meeting carried a hint of that. Apparently he felt a spark of recognition. Rita and I were standing in the lobby of the H Street hotel that had been taken over by the TM organization and converted into a residence for people who had joined the movement full-time. We were near the elevators, waiting for a glimpse of Maharishi as he left the exit hall. As he came through the crowd, a number of people handed him a flower and murmured a greeting. Somehow he spotted us and immediately broke free, walking in our direction. From his armload of flowers he picked a long-stemmed red rose and handed it to Rita, then found another one for me.

“Can you come up?” he asked. “We can talk.”

Why he singled us out we never asked. Perhaps it was because we were Indian, or because someone told him I was a doctor. Whatever the reason, we were thrilled. Only later did I hear a more esoteric reason: gurus, it is said, spend a good deal of time rounding up lost disciples from a previous lifetime. I can’t say that I felt a spark of recognition on my side.

Maharishi was treated with awed devotion by his Western followers, and it made Rita and me uncomfortable. We were grateful to be allowed to be ourselves. From the beginning there was a relaxed, congenial atmosphere, with Maharishi making clear that we were accepted as two people from India who understood the spirituality we had all been born into. But this led to its own strains, especially at first, because in reality I knew very little about my spiritual heritage. What eased my way was that Maharishi had long ago decided that the West needed to be addressed on its own terms. This meant using science. I was embraced as a physician, someone who could translate meditation into brain responses, alterations of stress hormones, reduced blood pressure, and other benefits to the body.

If this had been my only role, I might have drifted away fairly soon. TM had been publicly circulating in America since the early Sixties. There was already a cadre of scientists, including at least one Nobel Prize–winning physicist, who had been attracted to TM. Research into the benefits of meditation, although still arcane, had become respectable. Dr. Herbert Benson, a cardiologist at Harvard Medical School, had taken the scientific side of meditation to its logical conclusion. In a bestselling book,

The Relaxation Response,

Benson set out to prove that the brain can reach a meditative state, complete with all the benefits to the body claimed by TM, without the rigmarole of a personal mantra and the trappings of Indian spirituality. Using the same style of meditation as TM, a person could silently repeat any common word (Benson recommended “one”) and an autonomic response would be triggered in the brain. Benson had considerable research to back up his claims.

The response was mixed in the TM camp, where the medical benefits

of meditation had been a way to get Westerners through the door. Maharishi deserved credit for insisting that meditation delivered such benefits in the first place. Without them, Indian spirituality would have languished, so far as the West was concerned, in a warm bath of religious sentiments and mysticism. Turning the exotic into the practical was a brilliant stroke. Because Benson and others with an antispiritual bent felt they could get all of meditation’s benefits without its tradition however, the spiritual core of TM was ignored. I felt quite differently: It was wrong not to see meditation as an avenue to higher consciousness. I knew that was controversial as viewed from the West. I couldn’t produce any medical validation for the existence of higher consciousness. And so it was somewhat odd to be treated like the prodigal son returning to the fold, a medical expert with Indian spiritual underpinnings.

Two years earlier, while we were in India, Rita and I had traveled with a good friend to Maharishi’s academy in Rishikesh where TM teachers were being trained. (Because of its religious connotations, I suppose, the word “ashram” was never applied to any TM facility in India or in the West.) We knocked on the gate, assuming Maharishi would be there. He wasn’t, but among the people we spoke to was Satyanand, a monk who had joined Maharishi’s movement and was put in charge of the Rishikesh facility. He was much more like a traditional disciple in an ashram than a Western meditator. Like Maharishi, he had a long, white, untrimmed beard and was wearing a dhoti, the traditional monk’s garment wound from a single piece of white silk. When Satyanand asked us if we meditated, using the Indian word for it,

Dhyan,

I explained that we had learned in the United States, in the city of Boston. He laughed in delight.

“Indians go to Boston to learn dhyan. It’s wonderful!”

Why did I accept the attentions of a famous guru in the first place? Some experiences as yet untold had happened to me. Years back in medical school I had a professor who took an interest in how the brain controls basic responses like hunger. Everyone experiences a daily rhythm of autonomic responses that arise without being willed:

We eat, breathe, sleep, have sex, and become aroused to fight or flight by sudden stress. This man had done pioneering work in locating the hunger center in the brain, but he was also interested in how automatic responses can be controlled at will. In India yogis and swamis put on demonstrations of extreme bodily control as proof that they have attained mastery over their bodies.