Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (25 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

We were both now citizens of the most beautiful country in the world, and so was our eldest daughter, Ratika Priya. We were officially Indian-Americans. In reality we were caught between two worlds. When I reflected on India I thought about the extended families, spirituality, scintillating colors, and enchanting sounds. But when I thought about my new, adopted country, I reflected on freedom, the land of unparalleled opportunity, the country where I wanted to see my children have roots.

I have now traveled the world. Not too long ago I came across a billboard that read

THE ONLY TRUE NATION IS HUMANITY.

That truly resonates for me.

15

..............

An Obscure Light

Deepak

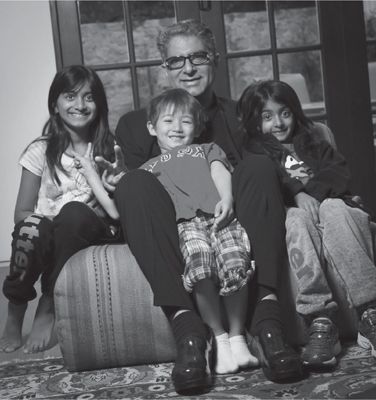

Deepak enjoying time with his grandchildren Tara, Leela, and Krishan, 2011.

W

E HAVE WORDS IN ENGLISH

for illumination and parables about the road to Damascus. The sudden stroke of awakening is very dramatic. But it would be helpful to have a separate word for a slow-motion epiphany. The reason it doesn’t exist, I suppose, is that slow epiphanies often aren’t recognized until years later, with a backward glance.

After storming out of my residency and severing all ties with the Tufts-affiliated hospital, the way forward seemed hopelessly blocked. Endocrinology didn’t seem to be in my future anymore. I felt stymied. On the positive side, my replacement job at the ER in Everett paid a living wage, much more than my fellowship had. When I showed up there, expecting to moonlight for hourly wages, I was met by the only full-time ER doctor, who was overwhelmed, and he offered me a full-time position on the spot. I protested that I wasn’t really qualified in emergency medicine, but he waved away my objections, saying that he would train me. Rita was pregnant with our second child at the time, but my work was so demanding that we barely saw each other in passing.

One night while I was on duty, Rita called me in the emergency room. “Congratulations, you have a son.” At first I didn’t understand what had happened.

When she had started having contractions, Rita gathered her maternity things and drove herself to the hospital (her mother, who had come from India to stay with us, was the nervous passenger), and hours after giving birth she phoned me. It’s an accomplishment to make it safely downtown through the tangle of Boston traffic in the first place. It was strange to hear all of this in between trauma cases at work and I was sad that I couldn’t break away when I got the news. But that was our life.

We decided to name the baby Kabir, in tribute to one of India’s

most revered poets. My mother used to have friends come in for

kirtan,

ceremonial singing and chanting. Someone would play the harmonium while the ladies sang songs that were often by Kabir.

The poet Kabir has a lovely story attached to him as well. He was an orphan in Benares, and no one knows what religion his parents followed. As a baby he was adopted by a poor Muslim couple who taught their child the weaving trade that he pursued his whole life. Kabir looked beyond Islam, however, and tricked a guru named Ramananda into giving him a Sanskrit mantra to meditate on. But this didn’t signify that he thought of himself as Hindu, either. When Kabir died in 1518, the Muslims wanted his body in order to bury it, while the Hindus wanted the body to cremate it. A heated argument arose. Someone drew aside the cloth that was draped over the corpse. Miraculously the body had turned into a bouquet of flowers. This was divided, and the Muslims buried their half while the Hindus burned the other.

My mother loved Kabir, but she had a social qualm about giving the baby his name. She didn’t want him to grow up with strangers assuming that someone named Kabir, which is Arabic for great, was Muslim. Rita and I went back and forth. In the end we chose Gautam instead, a common name in north India; we were pleased by the association with the Buddha, who went by Gautama when he left home and took up life as a wandering monk.

The ER job paid $45,000 a year, a dreamlike sum to us. We had graduated from a savings account to credit cards, feeling more and more American along the way. We bought our first house for $30,000 in the comfortable bedroom town of Winchester. But nothing brightened my anxiety that I was at a dead end professionally. It took almost a year for anything to move. Then I got an unexpected call from an academic researcher, a colleague I’d known for some time but had almost forgotten about. He was chief of medicine at the Boston VA Hospital in Jamaica Plain.

“I hear you’re looking for another fellowship,” he said. “How would you like to come work for me and finish your endocrine boards?”

“You know my history,” I said cautiously.

“Yeah.” I could hear the smile in his voice.

Later it occurred to me that he meant “That’s why I’m calling you.” My former adviser was personally disliked among other research doctors. He had treated all of us junior fellows with disdain, in the apparent belief that insulting other people’s intelligence was a way to prove his authority. None of this dislike was out in the open when I was hired. The only condition that came with the fellowship was that I would serve as chief resident at the VA. In itself this was a coup for them, since it was unusual to get a board-certified internist for the role.

After my residency in endocrinology was completed I passed the boards in 1977, which meant that I was now both a board-certified internist and an endocrinologist. Since I had lost two years along the way, Sanjiv took his boards in gastroenterology at the same time as me. But I was satisfied. All my educational aims were fulfilled. On the research side I spent my time at the VA studying the thyroid gland, as I had before. I wound up publishing a couple of papers and was rewarded with a small but growing reputation. The black marks from my previous altercation were erased.

If I vaguely questioned how the system worked, I still had every intention of working within it. Rebelling wasn’t the only way to get things to change. I would be complimenting myself without cause to claim that rebellion ever crossed my mind. As brilliant as scientific medicine can be, I was walking through the wards completely blind to another reality. This was the reality of a patient entering the hospital. Almost always he is frightened and sometimes concealing deep dread. His health and perhaps his life are at risk. The admissions process is impersonal. If there is the looming prospect of a huge hospital bill at the end, as there often is, more anxiety is piled on. The probing and prodding from doctors carries a measure of indignity as the patient sits naked under a flimsy green gown on a cold metal table.

These are not superficial changes from normal life. Doctors talk in a jargon that is mostly unintelligible to the average person. A mechanical routine is imposed once you arrive at your hospital room, an antiseptic and alien place. Orderlies and nurses come and go with

only a passing interest in your human side. The interview with the surgeon, if surgery is what you have been admitted for, lasts barely fifteen or twenty minutes, and you are too nervous to remember all the questions you wanted to ask—they run obsessively through your mind as you lie sleepless in bed staring at the ceiling.

The two realities of patient and doctor are almost like victim and persecutor, even though there are good intentions on both sides. No one addresses how terrible it feels for a patient to be depersonalized, even as it is happening. We’ve all seen enough TV to know that doctors talk about “the pancreatic cancer in room 453,” not “anxious Mr. Jones in room 453.” If a surgeon successfully removes a malignant tumor, he thinks to himself—at least at that moment—that he has “saved” the patient, without much concern for what is often a dire prognosis and, ultimately, death. It’s not a tribute to human nature that the one who holds all the power, the physician, is inured to the plight of the one who has no power at all, the patient.

I was ensconced in America, but India was about to reclaim me. It didn’t feel as if she needed to. Our friends included many Indian doctors, just as in Jamaica Plain. Sanjiv had brought his family to Boston, so there was no rupture in our relationship. We felt as close as ever. The way we talked was no longer like two boys growing up. Career and family took precedence. We weren’t twin stars circling each other anymore. But the constellation felt secure with wives and children filling it out. Once I moved into private practice, Boston medicine provided what it had promised all along, a community of the best hospitals staffed by physicians who also thought of themselves as the best.

This doesn’t turn into a story about disillusion. Cynicism didn’t corrode my heart and spoil my contented life. Once I gave up working the inhuman hours of a resident and the all-nighters at an emergency room (two things that had been a constant for six years), I did what established doctors do everywhere.

My day began around five in the morning. I would get up, grab breakfast on the run, begin stoking my energy with strong coffee, and

drive to the hospital. I was affiliated with two hospitals, located in Melrose and Stoneham, which meant that I was an attending physician. These were the places where my private patients were admitted if they needed surgery or hospital care.

I would make morning rounds, checking in on my admissions, and then drive to my office around eight. The next nine hours would be filled with appointments. My rapport with patients was still good, and I built up a sizable load—at its peak I think my practice had more than seven thousand patients on file. As the day wound down it was back to the hospital for evening rounds, and then home again. The whole cycle, which was repeated for the next decade, mirrored the routine of every other doctor I knew. Out before dawn, home after dark. Rita and her friends, who were also doctors’ wives, raised their families around the demands of their husbands’ work. It was simply accepted.

Medical training postpones the process of maturing as a person. I had been a full-time student until I turned thirty. One aspect of surviving in such an immature station was to remain immature, listening to authority, staying at the bottom of the ladder, reassuring yourself that you had more to learn. American doctoring is incredibly selfish if viewed as a climb into the elite echelon of moneymaking. The American dream at its crassest is the American paycheck. Once my annual income crossed $100,000, Rita and I were staring at money that felt surreal. The house we finally settled in, which was in Lincoln, another comfortable bedroom town outside Boston, cost six times what the first one had. The Seventies were our coming-of-age decade. Hidden from view was something I barely considered: If you don’t mature on time, you may never get a second chance.

What I began to notice instead was that my world was narrow and filled with rituals. In Jamaica Plain our Little India had been glamorous in a reverse way, with the nervous excitement of high crime and the daring of living from hand to mouth. One day I came home exhausted and collapsed in bed. Rita had gone out on errands. Suddenly there was a crashing sound from the living room. Jerked awake by adrenaline, I rushed into the living room. A threatening

black man had invaded my home. He stopped in his tracks, sizing me up. My mind raced immediately to the baby, who was asleep in her crib. I grabbed a baseball bat and charged at him. (The bat was a present from an American friend who wanted to coax me to stop fixating on cricket.) Before he had a chance to react, I swung hard at the intruder’s lower back and knocked him down.

The scene instantly became chaotic. Neighbors rushed in. Rita came home with groceries in her arms to see the baby screaming with fright on the living room floor next to a stranger swearing and writhing in pain. The police arrived, and I was trying not to seem jacked up on adrenaline—it wasn’t lost on me that I was under the influence of an endocrine hormone. It turned out that the intruder was an escaped convict who was quickly returned to prison.

Being in the suburbs among well-heeled Indian doctors was a duller existence. We kept our roots by doing the daily puja ceremony at home with an oil lamp and incense. As the children grew up, the girls went off to learn traditional Indian dances, called

Bharatiya Ratnam,

while the boys devoured Indian comic books filled with the exploits of Rama and Krishna. We drew into a tighter circle from knowing that, to many white doctors in Boston, Indian doctors were less skilled and suspect. Their silent rejection didn’t keep us from copying their lifestyle, however.

The American customs we were most proud of showed how insecure we actually were. Weekend barbecues and cocktail parties were indistinguishable from the ones seen in television commercials for charcoal lighter fluid and Kentucky bourbon. Among the men conversation consisted of a running contest over the cars we bought and the size of the color televisions in our living rooms. I heard about one doctor who was worried that being Indian meant his offspring would grow up too short to play varsity football. He undertook the drastic measure of putting his preteen kids on human growth hormone, which was illegal. As an endocrinologist I wished that I could warn him about possible side effects, including cancer, but we had no personal contact.