Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (10 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

We arrived at the sthan and were met by dignitaries who had somehow gotten wind of our visit. An elder gave a short speech. I was asked for a few words, and then they asked my father, who was eighty by then. He spoke more than a few words, but soon we arrived at the door of the sthan, where another group of dignitaries flanked us, insisting on performing some necessary prayers and offerings.

The helicopter pilot jiggled my elbow.

“You can’t go in.”

“Why not?”

It turned out that he wasn’t authorized to fly the helicopter at night, and since evening was approaching we departed, with extreme reluctance. As soon as I could reach a telephone I called the pundit that Arvind Sharma had put me in touch with. He listened in silence while I recounted our frustrating trip.

“It doesn’t matter,” he finally said. “You didn’t use the mantras anyway. Your chart told me you wouldn’t.”

When a circle is about to close, we often don’t pay attention. I thought I was through with Bhrigu, but I wasn’t yet. Sitting alone in my office, I had a brainstorm. Grabbing a cell phone, I called my father.

“Tilak,” I said with some excitement. “He must have had Klinefelter’s syndrome.” It all fit medically—his effeminacy, the combination of woman’s breasts and male sexual parts. Klinefelter’s is a genetic rarity, the result of a male baby having an extra X chromosome. Normally a girl baby is born with two X chromosomes and a boy with an X and a Y. But Tilak, along with perhaps one embryo in

a thousand, was born XXY. Some people with Klinefelter’s syndrome grow up exhibiting few or no symptoms, but he had most of them, including low fertility and premature death.

After a pause, my father agreed. “It fits.”

He was reluctant to say anything else about his ill-fated brother, but I pressed him. Did he think that Tilak had really known about a past life?

“I don’t like to talk about things I cannot explain,” Daddy replied.

Our talk drifted to other things, but there was a silent click as two worlds found a way to fit together. Science and mysticism, Bhrigu and Klinefelter’s. They were each more comfortable claiming to be the only

real

reality. But India holds both in a wriggling embrace, and almost invisibly I had reached the point where I did, too.

6

..............

Rama and Lakshmana

Sanjiv

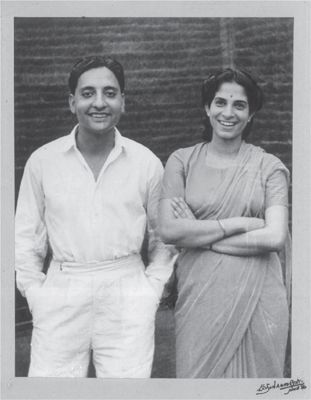

Sanjiv, sixteen, on a holiday break while a premed student at Delhi University, Pune, 1965.

M

Y MOTHER OFTEN TOLD DEEPAK

and me the story of Lord Rama and his younger brother, Lakshmana. Deepak and I related them to our own relationship just as we were supposed to. Lakshmana is greatly respected in the Indian tradition for his loyalty to his older brother, even at the cost of his own happiness. In most of these stories Lakshmana is much more emotional than his brother, but after Rama’s wife, Sita, is kidnapped, Rama becomes so angry he almost unleashes a weapon capable of causing tremendous devastation on the world. Lakshmana stops him, for once the voice of reason.

In our childhood, Deepak was certainly more responsible than I was, although at times he did take advantage of the fact that he was the leader. Deepak and I would play with our closest friends, Ammu and her older brother Prasan. We were so close that each year we celebrated Rakhi, a holiday when a sister ties a thread around her brother’s wrist to celebrate their relationship and pray for his health. In addition to tying a ceremonial thread around Prasan’s wrist, Ammu would tie a thread around my wrist and Deepak’s wrist. So when Deepak ordered Ammu, Prasan, and me to run back and forth one hundred times while he timed us, that was exactly what we did, obeying happily. Deepak was older than us, so we believed he must know more than we did. If he told us to climb the tree in our backyard, we climbed that tree—and when Deepak told us to jump out of that tree, we jumped. Luckily no one got hurt.

We trusted each other. Deepak had enough faith in my abilities that when I was shooting my air rifle at a can sitting on a post, he stood behind the post and told me to continue.

I put down the gun. My aim was good but not perfect—I didn’t want to take the chance. But Deepak insisted, telling me the story of

William Tell and his son. This put me in a difficult quandary: Do I fire the gun and risk seriously hurting my older brother, or do I disobey him?

I fired the gun and hit him in the chin.

I wanted to run into the house and get help, but Deepak, whose chin was bleeding, ordered me to stay put. He quickly made up a story about tripping on a barbed wire fence; he wanted us to lie to our parents to avoid a reprimand. That was a difficult thing for me to do, but as they always told us, he was Rama and I was Lakshmana. I proved my loyalty by going along with the story.

Over the next couple of days, Deepak developed a swelling on his chin. Our grandmother noticed this and brought it to my father’s attention at dinner.

“You’re the brilliant doctor,” she said, “but I don’t believe you’ve properly diagnosed your own son’s condition. There’s probably a piece of barbed wire in his chin. Take him for an X-ray tomorrow and check it out.”

The next morning Deepak went with our father to the hospital. At home I paced the veranda nervously, watching for my brother and father’s return. Every few minutes I would go inside and check with my mother.

“Did they call from the hospital yet?” She looked at me with suspicion.

“You seem awfully concerned.” Just then the phone rang and my father told my mother that the X-ray showed an air rifle pellet lodged in Deepak’s chin. A surgeon had been summoned to remove it. We were admonished to tell the truth but not punished.

Over the years Deepak developed a dimple in his chin. I think it makes him look dignified and noble, but it also reminds me of the episode every time I see him.

While Deepak and I were close, we were also very competitive. We were never truly rivals, but we did try to one-up each other. We would try to determine who could swim a hundred laps the fastest, who could play the fiercest game of table tennis or chess, who could outrace the other on a pair of roller skates, who had the strongest vocabulary.

I wanted to beat him every single time, and Deepak felt the same. Even though I was his younger brother, I don’t recall him ever letting me win. I guess we learned that competing to the best of your ability built character more than being allowed to win. And when it came to sports, I was often able to win despite the age difference.

Deepak eventually got even with me for shooting him. We were fighting with wooden swords one day, when Deepak accidentally cut me on my nose. I was left with a slight scar there, neither as noticeable nor as dignified as Deepak’s dimple.

My family instilled great confidence in both Deepak and me, sometimes more than might have been warranted. We were surrounded by accomplished people: our father, the renowned doctor; our uncle, the heroic admiral; another uncle, the well-known and respected journalist; and so on. We were told, repeatedly, that we were capable of achieving whatever goals we set for ourselves. As a result, neither of us ever backed down from a challenge—that I can recall. For Deepak those challenges were usually academic; for me they were often physical. Kids fight, and Indian children are no exception.

For instance, when we were at school in Jabalpur, we all had to deal with a tough classmate everyone called Roger the Bully.

During our lunch break, we often played marbles. The players would put a certain number of marbles in the circle and then each one would try to knock as many as possible outside the perimeter with his striker marble, slightly larger than the rest.

One day one of the other kids came to school with some beautiful Chinese strikers. We made a deal: three of my ordinary marbles for one of his special Chinese ones. I was good at the game, and that day won the whole pot in less than twenty minutes, an impressive feat. I was feeling quite proud of myself, until I heard the voice of Roger the Bully behind me.

“Give me half.”

This was a moment every young child fears, no matter where in the world they might be: the bully demanding his share. Everybody in the school was afraid of Roger, even Deepak. But I turned to look up at him.

“I’m not giving you any marbles,” I blurted. “These are mine. Why should you have any?”

I have to admit that if these were ordinary marbles I might have given them up to avoid a conflict. Roger was a year older than me and at least three inches taller. But these Chinese marbles were beautiful. I had made a fair trade, won the marbles matches, and wanted to keep my entire winnings.

When I challenged Roger he immediately went into a boxing stance, like he was about to thrash me. So I stood up and decked him. I didn’t stop to think about it—I just hit him right on the chin and knocked him on the ground.

The older boy looked up at me with fear in his eyes. And then, to the surprise of everyone in the yard, Roger the Bully burst into tears.

That incident was the end of Roger’s bullying, and it turned me into something of a school hero. And surprisingly, Roger the Bully and I became friends.

We had been taught to stand up for ourselves from a very young age. Our parents always asked us how we felt about things that affected our family, and took our answers very seriously. They encouraged us to speak up, a lesson that both Deepak and I obviously learned. Once, when I was about four years old and in first grade, my father took me with him to the market to pick up a crate of Coca-Cola. At that time I had the habit of sucking my thumb; my parents had tried everything to get me to stop, with no luck. As we drove around a curve we saw a car on the side of the road with a flat tire.

“Do you know why that car has a flat tire?” my father asked.

“No.”

“Because the son sitting next to me is sucking his thumb.” I pulled my thumb out of my mouth and looked at him. As we drove along I thought about what he’d said and, in some strange way, understood the point my father was trying to make.

I was a somewhat precocious four-year-old, a quick learner, and our father had a habit that bothered me—for more than twenty years he had smoked two packs of cigarettes a day.

A little farther up the road, we came upon a huge truck lying on its side. Policemen and medical personnel were on the scene. I stared at the scene, illuminated by flashing ambulance lights, as we drove by.

“Dad, did you see that lorry?” I asked. “Do you know why it happened?”

My father smiled and asked me why.

“Because the father sitting next to me smokes cigarettes!”

In the years since, I have learned the bittersweet pleasure of having your child use the lessons you’ve taught against you. In this instance my father thought about it for several seconds and then rolled down the window of the blue Hillman car he was driving and flipped his cigarette into the street. I smiled smugly. Then he went further. He took out a Ronson lighter that had been a gift to him from a British officer. He looked at me and then tossed it out the window. Within a couple of weeks he had stopped smoking completely and never smoked again. Naturally I stopped sucking my thumb, too.

Our father wrote in his book,

Your Life Is in Your Hands,

that “parents must foster a warm and friendly relationship with their children, and encourage them to develop diverse interests.” My parents did this successfully, and Deepak and I admired both greatly for it. We each carry with us elements of their characters, their core values and principles, which in turn we have tried to pass on to our own children.

Growing up in India as the children of a respected physician allowed us to enjoy many privileges. Once, after my father had treated a prince from an Indian state, we were invited to stay in his palace.

Deepak and I woke up early in the morning and went out to the palace balcony. I looked down into the courtyard and couldn’t believe my eyes. I literally rubbed my eyes to be sure I wasn’t dreaming. Down below was the most majestic animal I had ever seen: a beautiful pure-white tiger. This was, in fact, the first living white tiger seen in nature. Its name was Mohan. It had been captured by the prince as a cub and he had raised it himself.

That was the India of our childhood: beggars outside the high walls protecting the wealthy, the sounds of merchants hawking their

goods, while inside a white tiger sat placidly on a perfectly manicured lawn. But what Deepak and I learned was that we had been given a great deal, and that in return it was our dharma to behave responsibly, to respect other people, and to give back at every conceivable opportunity.

That, in essence, is the path that both of us have followed.

7

..............

Laus Deo

Deepak