Brunelleschis Dome (3 page)

Read Brunelleschis Dome Online

Authors: Ross King

Despite all the challenges it presented, Neri di Fioravanti’s model set the basic form for the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore as it would ultimately be constructed. Intriguingly, it was to consist of not one but

two

domes, with one shell fitting inside the other. This type of structure was rare, though not unique, in western Europe.

5

Developed during the medieval period in Persia, it had become a characteristic feature of Islamic mosques and mausoleums. In such structures a tall outer shell was intended to give impressive height to the building, while the shallower inner one — which partially supported the outer dome — was more suited to the interior proportions. The outer dome also shielded the inner one from the elements, serving as a weathering skin.

Besides the double shell, the other special feature of Neri’s dome was its particular shape. Unlike most previous cupolas, including the Pantheon, that of Santa Maria del Fiore was to be pointed rather than hemispheric in profile. That is, instead of describing a semicircle, its sides would curve up toward a point in the same way that Gothic arches do. This shape was known as a

quinto acuto,

“pointed fifth.” In technical terms the dome was to be an octagonal cloister-vault composed of four interpenetrating barrel vaults. This complex structure was to create unforeseen problems for the men who began to build it fifty years later, and its construction would call for ingenious solutions.

Neri’s model of the dome became an object of veneration in Florence. Standing 15 feet high and 30 feet long, it was displayed like a reliquary or shrine in one of the side aisles of the growing cathedral. Every year the cathedral’s architects and wardens were obliged to place their hands on a copy of the Bible and swear an oath that they would build the church exactly as the model portrayed. Many aspiring carpenters and masons must also have walked past it on their way in and out of the cathedral, contemplating the problems of the dome’s construction and dreaming of their solution. Thus when the competition to solve these difficulties was announced in the summer of 1418, more than a dozen models were submitted to the Opera by various hopefuls, some by craftsmen from as far away as Pisa and Siena.

However, of the many plans submitted, only one — a model that offered a magnificently daring and unorthodox solution to the problem of vaulting such a large space — appeared to show much promise. This model, made of brick, was built not by a carpenter or mason but by a man who would make it his life’s work to solve the puzzles of the dome’s construction: a goldsmith and clockmaker named Filippo Brunelleschi.

HE

G

OLDSMITH OF

S

AN

G

IOVANNI

I

N

1418 F

ILIPPO

B

RUNELLESCHI

— or “Pippo,” as he was known to everyone — was forty-one years old. He lived in the San Giovanni district of Florence, just west of the cathedral, in a large house he had inherited from his father, a prosperous and well-traveled notary named Ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lappi. Ser Brunellesco originally intended his son to follow in his footsteps, but Filippo had scant interest in a career as a civil servant, showing instead, from a young age, an uncanny talent for solving mechanical problems. No doubt his interest in machines had been sparked by the sight of the half-built cathedral that stood a short walk from the family home. Growing up in the shadow of Santa Maria del Fiore, he would have seen in daily operation the treadwheel hoists and cranes that had been designed to raise blocks of marble and sandstone to the top of the building. And the mystery of how to build the dome was probably a topic of conversation in the family home: Ser Brunellesco possessed some knowledge of the subject, having been one of the citizens who in the referendum of 1367 had voted for the bold design of Neri di Fioravanti.

Although disappointed by his son’s lack of desire to become a notary, Ser Brunellesco respected the boy’s wishes, and when he was fifteen Filippo was apprenticed in the workshop of a family friend, a goldsmith named Benincasa Lotti. An apprenticeship with a goldsmith was a wise and logical choice for a boy showing mechanical ingenuity. Goldsmiths were the princes among the artisans of the Middle Ages, with a large scope to explore their numerous and varied talents. They could decorate a manuscript with gold leaf, set precious stones, cast metals, work with enamel, engrave silver, and fashion anything from a gold button to a shrine, reliquary, or tomb. It is no coincidence that the sculptors Andrea Orcagna, Luca della Robbia and Donatello, as well as the painters Paolo Uccello, Andrea del Verrocchio, Leonardo da Vinci, and Benozzo Gozzoli — some of the brightest stars in a remarkable constellation of Florentine artists and craftsmen — had all originally trained in the workshops of goldsmiths.

Despite its prestige, goldsmithing was not the most wholesome of professions. The large furnaces that were needed to melt gold, copper, and bronze had to burn for days on end, even in the heat of summer, polluting the air with smoke and bringing the danger of explosions and fire. Noxious substances such as sulfur and lead were used to engrave silver, and the clay molds in which metals were cast required supplies of both cow dung and charred ox horn. Worse still, the workshops of most goldsmiths were found in Florence’s most notorious slum, Santa Croce, a marshy and flood-prone area on the north bank of the Arno. This was the workers’ district, home to dyers, wool combers, and prostitutes, all of whom lived and worked in a clutter of ramshackle wooden houses.

Filippo thrived in this environment, however, quickly mastering the skill of mounting gems and the complex techniques of niello (engraving on silver) and embossing. At this time he also began studying the science of motion, and in particular weights, wheels, and gears. The immediate fruits of these investigations were a number of clocks, one of which is even said to have included an alarm bell, making it one of the first alarm clocks ever invented. This clever device — of which, unfortunately, no evidence survives — appears to have been the first of his many stunning technical innovations.

1

Filippo matriculated as a master goldsmith in 1398, at the age of twenty-one, then rose to citywide prominence three years later during a competition that, for its intense public interest, rivaled the one between Giovanni di Lapo Ghini and Neri di Fioravanti twenty-five years earlier. This was the famous competition for the bronze doors of the Baptistery of San Giovanni.

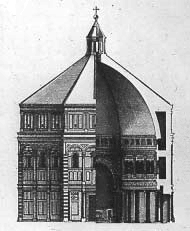

The Baptistery of San Giovanni.

This competition — which would play a pivotal role in Filippo’s career — came about because of an outbreak of plague. The Black Death was a faithful visitor to Florence. It arrived, on average, once every ten years, always in the summer. After the horrors of 1348, there were further outbreaks, less severe, in 1363, 1374, 1383, and 1390. Various remedies were invented to drive it away. Church bells were violently rung, firearms discharged into the air, and the portrait of the Virgin from the church at nearby Impruneta — an image with miraculous powers that was said to have been painted by St. Luke — borne in procession through the streets. Those rich enough escaped into the country. Those who stayed behind burned wormwood, juniper, and lavender in their hearths. Ox horn and lumps of sulfur were also burned, because stenches were considered equally effective in clearing the air. So intense were these fumigations that sparrows would fall dead from the rooftops.

One of the worst outbreaks occurred in the summer of 1400, when as many as 12,000 Florentines died — that is, just over one person in five. The following year, in order to appease the wrathful deity, the Guild of Cloth Merchants decided to sponsor a new set of bronze doors for San Giovanni. The Baptistery, at whose font every child in Florence was baptized, had long been one of the city’s most venerated buildings. An octagonal, marble-encrusted, domed structure standing a few yards to the west of the rising hulk of the new cathedral, it was believed, erroneously, to be a Temple of Mars constructed by Julius Caesar to celebrate the Roman victory over the nearby town of Fiesole (in fact it was built much later, probably in the seventh century

A.D.

). Between 1330 and 1336 the sculptor Andrea Pisano, later one of the cathedral’s

capomaestri

, had cast bronze doors to ornament it: twenty panels showing scenes from the life of John the Baptist, the patron saint of Florence. But no further work had since been done to beautify the Baptistery, and Pisano’s doors had themselves fallen into disrepair.

Filippo was in Pistoia in 1401, having left Florence because of the plague. There he had been working in collaboration with several other artists on an altar in the cathedral — a prestigious commission — but he returned to Florence immediately upon hearing of the competition. Thirty-four judges were selected from among Florence’s numerous artists and sculptors, along with various worthy citizens, including the wealthiest man in Florence, the banker Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici. These judges were charged with choosing the winner from among seven goldsmiths and sculptors, all of them Tuscans.

The plague was not the only threat to Florence at this particular time. No sooner had the pestilence abated than a new danger, potentially worse, hove into view, with serious repercussions for, among other things, Santa Maria del Fiore. Work on the new cathedral had been moving on apace. The great arches over the main pillars that would support the cupola had The Goldsmith of San Giovanni been started in 1397, and the chapels on three sides of the octagon were in the process of being vaulted. The Piazza dell’Opera, a triangular space to the east of the cathedral, had been laid out and paved, and a new building had been built to house the Opera del Duomo. Early in 1401, however, this activity abruptly ceased when the Duomo’s masons were conscripted into service fortifying the walls of Castellina in Chianti, a small town on the road to Siena. Soon afterward the Signoria, the executive body of the Republic, hastily ordered them to fortify those of two other towns, Malmantile and Lastra a Signa, both on the road to Pisa.

The reason for this sudden flurry of building was a threat from the north: Giangaleazzo Visconti, the duke of Milan, against whom the Florentines had fought a war ten years earlier. Giangaleazzo was a gingerbearded tyrant, cruel and ambitious, whose coat of arms was suitably grisly: a coiled viper crushing in its jaws a tiny, struggling man. His autocratic rule differed drastically from the “democracy” of Florence, which fulfilled Aristotle’s criterion for an ideal republic in that it elected its rulers (albeit with a narrow franchise) to short terms in office. In 1385 Giangaleazzo had seized power in Milan by imprisoning and then poisoning his uncle, Bernabò Visconti, who also happened to be his father-in-law. To befit his new status, Giangaleazzo had bribed the emperor Wenceslas IV to grant him the title of duke of Milan. He had also begun work on a new cathedral in Milan, an enormous Gothic structure complete with pinnacles and flying buttresses — precisely the sort of architecture to which Neri di Fioravanti and his group had objected.

It was this old enemy, then, whose shadow now fell over Florence. Not content with his power in northern Italy, Giangaleazzo was proposing to unite the entire peninsula under his rule. Pisa, Siena, and Perugia had already been subdued, and by 1401 only Florence stood between him and lordship of all northern and central Italy. Florence was politically and geographically isolated, cut off from the seaports of Pisa and Piombino. Under siege from Giangaleazzo, her trade came to a standstill, and famine threatened. The Milanese tyrant even prevented Florence from importing supplies of the wire that was used to make instruments for carding wool. As his troops moved on Florence, the historic rights of the Republic looked doomed.

It was against this background of urgency and crisis that the competition for the second set of bronze doors was played out. The rules of the competition were simple. Each of the candidates was given four sheets of bronze, weighing seventy-five pounds in all, and ordered to execute a scene based on an identical subject: Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac as described in Genesis 22:2-13. This story is traditionally said to prefigure the crucifixion of Christ, but to the Guild of Cloth Merchants, with Florence “miraculously” delivered from the plague and with Giangaleazzo’s armies fast approaching, more immediate analogies may have suggested themselves in this tale of sudden salvation from mortal threat.

2

The competitors were given one year to complete their trial panels, which were to be some 17 inches high by 13 inches wide.

A year may seem like a long time to execute such a relatively small work, but casting in bronze was a delicate operation demanding a high degree of skill. The first step in the process was to model the figure roughly in carefully seasoned clay over which, once the clay had dried, a coating of wax was laid. After the wax had been carved into the shape of the desired statue or relief-work of extreme sculptural precision — a new layer was laid over it: a combination of burned ox horn, iron filings, and cow dung was mixed together with water, worked into a paste, and spread over the wax-coated model with a brush of hog sables. Several layers of soft clay were then applied, each of which was allowed to dry before its successor was overspread. The result was a shapeless mass bound together with iron hoops — the lumpy chrysalis from which the bronze statue was to emerge.