Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know (18 page)

Read Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know Online

Authors: David I. Steinberg

Damage from Cyclone Nargis on Haing Gyi Island, in the Irrawaddy division of southwest Myanmar, May 7, 2008. (AFP/AFP/Getty Images)

U Nu, or Thakin Nu, the Burmese prime minister, during his time under house arrest, guarded by the Burmese Army on behalf of general Ne Win, March 2, 1962. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

General Ne Win (1911–2002), the first military commander to be appointed as prime minister of Burma (Myanmar). (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

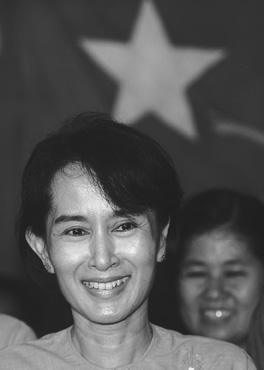

Aung San Suu Kyi listens to a question during a press conference on May 6, 2002, in Yangon. (STEPHEN SHAVER/AFP/Getty Images)

As in many parts of the world, the United States provided assistance to the government to eliminate the crop. The United States supplied helicopters (twenty-seven helicopters and twenty-eight other planes), pilot training, and other equipment, and surveillance increased. Because insurgent armies could shoot down the helicopters, their use was confined to areas in which the military had ground forces and could prevent this. Much of the production was beyond their military capacity to control, however; the effects were limited in that period. The United States cut off assistance for aerial spraying of the poppy fields after the coup of 1988.

Perhaps because of international opprobrium, the junta, under Khin Nyunt’s leadership, began a program of eradication of the opium crop. ASEAN as a whole had a target of 2015 as a drug-free region. This effort was at first treated with skepticism in international circles, but eventually the United Nations indicated that such production had become minimal compared to the previous decade (130,000 hectares under production in 1998, compared to 27,000 in 2007). In 2002, the United States and the junta met quietly to discuss steps to take Myanmar off the international narcotics list, but a number of congressional members sought to continue to isolate the regime, preventing this. There has been one negative effect: the loss of income for these hill dwellers has made them some of the most deprived people in the state. In the 1975–1985 period, 75 percent of all heroin imports into the United States came from Burma; in 2007, this figure was less than 2 percent. In that year, Afghanistan produced 93 percent of the world’s opium, and Myanmar only 5 percent. These encouraging statistics may well prove ephemeral, as other crops providing alternative incomes are not easily cultivated or marketable in those remote areas, and a return to poppy production is likely.

If opium production is down, drug production is not. Meth-amphetamines, chemically produced drugs with no agricultural base, are produced in Myanmar among the Wa and transported into Thailand, through which the chemical components are

imported back into Myanmar, and where it has became an important political issue. The Wa are the most heavily armed of the ethnic groups with which the government has verbal ceasefire agreements. They cannot be controlled by the

tatmadaw

. Even entry to their areas by any Burmese military personnel requires their approval. Prime Minister Taksin Shinawatra in Thailand in 2003 ordered a war against these drug dealers that resulted in nonjudicial government executions of over 2,800 dealers and others and causing a quiet confrontation with the United States and human rights groups over evident violations of human rights. An estimated 700,000 to 1 million tablets of methamphetamine enter Thailand every year from Myanmar, and they have become a scourge of Thai youth. Some 4 percent of the Thai population is said to use this drug. To protect this trade, the United Wa Army on the Myanmar side of the border has had skirmishes with the Shan State Army South, armed by the Thai and supported by the United States. These minority armies have become surrogates for the Burmese and Thai governments in that border region.

Minority religions have important negative and positive influences in society. The positive influences of solace and group solidarity result among peoples on the periphery, especially non-Buddhist groups. Three minorities have been especially prone to Christian conversions, and it is significant that few Buddhists are converted. Most conversions take place among animist populations. Foreign influences have become important, but under the constitution of 2008 no religious group in Myanmar will be able to receive or expend funds from foreign sources.

The most Christianized ethnic groups are the Chin and Kachin. The 1983 census notes that among the Chin in western Myanmar along the India border, about 70 percent were

Christian; some now say the figure is closer to 90 percent. Observers believe that perhaps 90–95 percent of the Kachin in northern Myanmar are now Christians. The Karen have been noted as prime converts to Christianity since the early nineteenth century when the American Baptist Mission went into Burma. Although accurate figures are lacking, some say about one-third of the Karen people are Christian, one-third Buddhist, and one-third animist.

Although foreign missionaries are no longer allowed residence in the country (most of those resident in 1962 were allowed to remain but could not return once they left), there are strong ties with external churches. They have maintained liaisons, churches in Burman areas are accessible, and seminaries still exist to train local pastors and priests. There have been charges of church burnings and oppression, especially in the east where Karen insurgents, many of whom are Christian, operate. The Chin State has also been the scene of harassment and forced labor to build Buddhist pagodas.

The charges by some foreign organizations that there has been a national concerted effort to wipe out or threaten Christians cannot be substantiated. There are, however, serious impediments to Christians rising in the military and the bureaucracy. There are evidently glass ceilings that prevent Christians from assuming senior positions, such as colonels or higher officers in the

tatmadaw

. Local military commanders have considerable latitude to act against minority religious groups, so occasionally incidents no doubt occur. Members of unregistered and informal Chin churches in Burman cities have been subject to harassment.

Muslim problems are more severe. Although mosques operate freely in major cities, there are severe prejudices that provoke outbursts. Muslim–Buddhist riots are an irregular but not uncommon occurrence in various towns and are usually based on some perceived insult by a Muslim to Buddhism or to a Burman woman. Some charge that such riots are engineered by the military to direct antagonisms away from the government

to helpless scapegoats. Beliefs persist even at the cabinet level that Muslims attempt to convert Burman women, and, if successful, Islamic organizations provide rewards depending on the social level of the converted person.

The most severe issue related to Islam is the plight of the Rohingyas on the Bangladesh border. This group is effectively stateless. They are not recognized by the government (and have not been so since the Panglong Agreement in 1947) as a minority group or a national “race.” The government has claimed that they are, in fact, Bengalis. They have no rights and cannot even legally leave their area in the townships along the border. Some tens of thousands have fled by sea to Malaysia, a supposedly a friendly Muslim state, but their status has been ambiguous. Thailand has turned some back out to sea. In 1978, Burmese police and troops made a sweep through that region and prompted more than 200,000 to flee into Bangladesh. Most were repatriated under UN auspices. A similar flight occurred in 1991–1992, and again there was UN repatriation (although some 10,000–15,000 still remain in exile). In January 2009, the government again denied that they were one of the state’s national “races.”

The military claims that these people are in effect illegal immigrants, and therefore they have no right to citizenship. The migrations along that portion of the Burma/Myanmar littoral from the early nineteenth century onward are complex. The fusion of India and Burma in the colonial period, and the exodus during World War II and in the current period, made matters even more murky. Burmese authorities have also charged that there is terrorist training among Muslims on the Bangladesh side of the border; through their military intelligence service they have monitored such activities. The Rohingya situation is far more severe regarding human rights violations than among any other minority. In August 2008, however, the government announced it would issue identity cards to some 37,000 Rohingya as a first stage in their registration, although whether this would give them improved status is questionable.

In acts that seem designed to demonstrate Burmese sovereignty over some of the border regions inhabited by both Christians and Muslims, the government has been building pagodas. They have been constructed in the Kachin State on the China border in a Christian area, and in the Rakhine State on the Bangladesh border in a completely Muslim area. General Than Shwe is said to believe that the most dangerous of the Burmese frontier regions is the one with Bangladesh. In historical terms, he is correct.

The role of Aung San Suu Kyi as the icon of democracy in Burma/Myanmar has led the expatriate Burmese opposition to make her birthday (June 19) an international women’s day. They have also protested the perceived subjugation of women under the present Myanmar government, especially exemplified by the house arrest and denigration of Aung San Suu Kyi. This has been compounded by charges of systemic rape of minority women by the Burman troops.

This movement is somewhat ironic, for among the major cultures of South and East Asia, the status of Burmese women has historically been higher. They traditionally married under their own volition. There was no foot binding in Burma as there was China, nor the practice of suttee (widow suicide) as in India. Burmese women had equal inheritance rights with their male siblings and retained control over their dowries. If there were a divorce, the wife would keep the dowry; this kept divorce rates low. Early English observers felt that the status of Burmese women was higher than that in Europe at the time, and one British observer in the early nineteenth century believed that Burmese women were more literate than English women. Burmese women not only control most family affairs but also have important economic roles; most trading in the bazaars is by women. In modern times, females equal males in the educational system, and

women have been prominent in the professions, especially in education and medicine.