Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know (2 page)

Read Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know Online

Authors: David I. Steinberg

What are the current and future strategic interests of foreign powers in Myanmar?

What is the future of the military in Myanmar under any new government?

What are the needs of the state in a transition to a new government?

Is democracy a reasonable expectation for Myanmar in the near term? In the future?

What might the role of the Burmese diaspora be in a new government?

With gratitude, I would like to acknowledge three groups of people who contributed to the production of this volume.

The first are those unnamed individuals worldwide who unwittingly and unceremoniously assisted in the writing of this work. Instructed by the publisher that there were to be no notes, I have uncharacteristically and with a considerable degree of guilt mined without citing the works of many distinguished scholars and others concerned with Burma/Myanmar, using their materials, ideas, and data. Without their silent participation, this could not have been written. To them I offer profuse apologies, and I promise to make their critical contributions to the field more publicly known in other fora. It is small recompense that the Suggested Reading section contains many of their works.

To my friends and acquaintances in Myanmar, whom I dare not publicly name, I thank you for indulging me over some fifty years. Your friendships and advice have been critical to whatever contribution I may have made to knowledge about this country and to me personally as well. If I have misrepresented or misinterpreted your country and culture, I apologize and assure you that it has not been intentional.

To those who helped me by commenting on drafts and correcting my egregious errors, many thanks. They include commentators such as Andrew Selth, Mary Callahan, John

Brandon, Matthew Daley, Dominic Nardi, Lin Lin Aung, Zarni, and some unidentified readers. My class on Burma/Myanmar at the School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, had access to an early draft and commented on it. I alone, however, am responsible for sins of commission or omission. To David McBride of Oxford University Press, who commissioned this work from me, I express my thanks for his initial confidence, his Herculean efforts to make this more readable, and in shortening my Proustian sentences that sometimes seem, even to me, interminable.

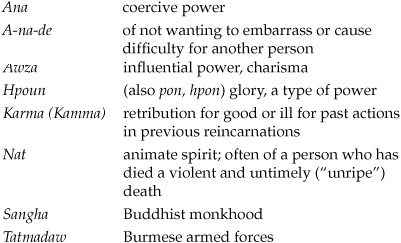

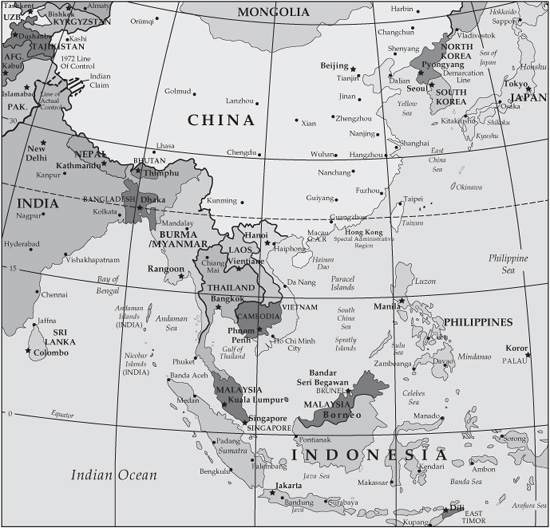

Southeast Asia (redrawn from a map produced by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in 2004)

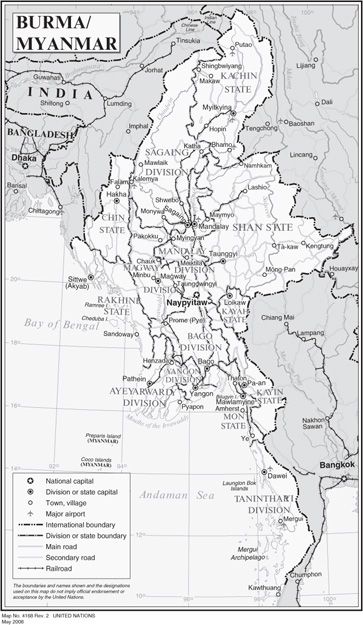

Administrative divisions of Burma/Myanmar (redrawn from a map produced by the United Nations in 2008)

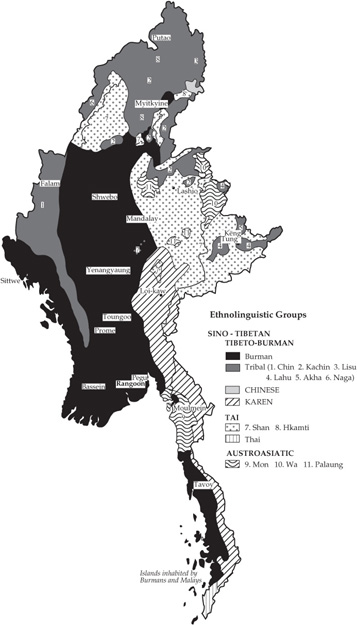

Ethnolinguistic map of Burma/Myanmar (redrawn from a map produced by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in 1972)

All names in Burma/Myanmar are personal—there are no surnames, even within the same nuclear family. When Burmese nationals publish or travel abroad, one of their names may be used as an unofficial surname for practical purposes. Names may be one to four syllables. Female names often have a double syllable (e.g., Lin Lin Aung). Names are normally preceded by a title based on a family designation:

U

(uncle) for a mature male

Daw

(aunt) for a mature female

Ko

(elder brother) a male somewhat older than the speaker

Maung

(younger brother) a more junior male

Ma

(younger sister) a more junior female

Bo

(military officer)

Bogyoke

(supreme commander)

Thakin

(lord) used by British in the colonial period and

adopted by some Burmese in the nationalist movement

Western titles are also used: Doctor, General, Senior General, Brigadier, and so on, as are Christian names (certain titles have become embedded in the name in foreign usage; e.g., U Nu, whose name is simply Nu, but when he began writing, his work was authored by Maung Nu).

Sometimes these words (U, Ko, Maung, etc.) may also be part of the name, and not a title (a male with a name of Oo Tin, might be known as Maung Oo Tin as a youngster, Ko Oo Tin as a college student, and U Oo Tin as a middle-aged man).

Names in the text are either spelled according the U.S. Department of State Board of Geographic Names or the personal preference of the individual. The following list of names are for those who appear in the book frequently.

Aung Gyi (b. 1919–) Brigadier, retired

Aung San (1911–1947) Architect of Burmese independence

Aung San Suu Kyi (b. 1945–) So named by her mother to remember her illustrious father; this is not normal Burmese usage

Khin Nyunt (1939–) Lt. General, Prime Minister, under house arrest (2004–)

Maung Aye (1937–) Deputy Senior General

Maung Maung, Dr. (1924–1994) President, August–September 1988

Ne Win (1920–2002) Generalissimo. Variously, President, Chair BSPP, Prime Minister, Minister of Defense

Nu (1907–1995) Former Prime Minister

Saw Maung (1928–1997) Senior General, Chair SLORC 1988–1992

Sein Lwin (1924–2004) General, President, July–August 1988

Than Shwe (1933–) Senior General, Chair SLORC/SPDC 1992–

Many countries have changed their names (Siam–Thailand, Ceylon–Sri Lanka, etc.), but none has caused as many problems as the Burma–Myanmar split, which has unfortunately become the surrogate indicator of political persuasion. In July 1989, the military junta changed the name of the state to the Union of Myanmar, from the Union of Burma. Myanmar was the

official written designation and an old usage, and this change was insisted on by the military to lessen (in its view) ethnic problems. The military has assiduously used

Myanmar

for all periods of Burmese history and does not use

Burma, Burmese

(as an adjective or for a citizen), or

Burman

(the majority ethnic group, the military uses

Bamah

). This has not been accepted by the political opposition, and although the United Nations and most states have accepted the change, the United States did not, in solidarity with the opposition. The Burmese government sees this as insulting.

In this volume, both

Burma

and

Myanmar

are used—

Myanmar

for the period since 1988 (the start of the present military government) and

Burma

for all previous periods, and Burma/Myanmar is used to indicate continuity of action.

Burman

is used for members of the majority ethnic group;

Burmese

is employed here as a designation of all citizens of that country of whatever ethnicity or linguistic predilection, as the official language of the state, and as an adjective. This usage should not be construed as a political statement. Place names are generally selected in accordance with traditional usage.

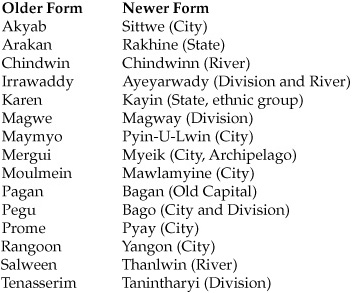

Other names have been changed. The older form will be used in the text because of enhanced familiarity, but some of the revised spellings are listed here.

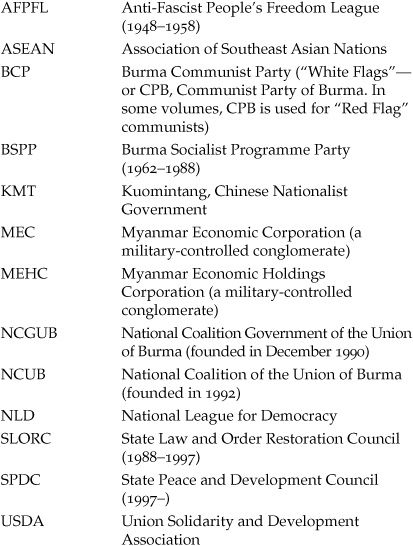

Acronyms

Burmese Words