Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (48 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

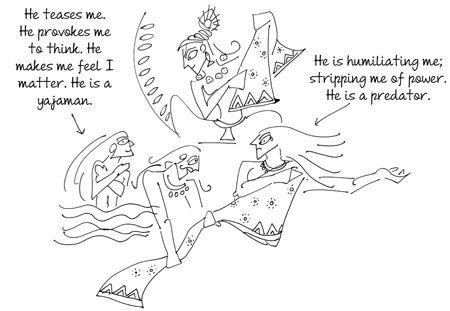

The yajaman who takes with the desire to dominate and domesticate is not on the path to becoming Vishnu. He will only create rana-bhoomi, not ranga-bhoomi, as he does not include the devata in his world. He wants to control the world of the devata rather than understand it.

Duryodhan dominates Draupadi because he feels she has hurt him. He wants to punish her. In his eyes, he is meting out justice. But he is capable of outgrowing his anger towards her by understanding her reasons for hurting him. The reason is invariably rooted in fear; when this is understood every villain, evokes karuna, compassion.

The idea of karuna is an essential thought in Buddhism. When we realize that people do what we consider villainous deeds out of fear, we do not condemn them, or patronize them, but find out in our heart what it is about us that makes them fear us too. Only when we recognize that perhaps we are the cruel parent, or we are perceived as the cruel parent, will we empathize with the Other. The story of Buddha's life is filled with instances where he meets angry beings: from a mad elephant to a murderous serial killer, Angulimala. They calm down before the Buddha because he 'sees' them and understands where they are coming from. They are not condemned for their behaviour; that their belief springs from fear is understood.

Karuna demands the expanding of the mind. This is visualized as the lotus. Hence Buddha is often shown holding a lotus, a gesture known as Padmapani, he who held the lotus. Sometimes the goddess Tara, embodiment of pragna, or wisdom, holds the lotus.

In every conversation, Sunil wants to dominate. He wants to come across as the alpha. He must know more than the Other. He must know things before the Other. He is constantly seeking Durga every time he dismisses those before him. The day he starts to listen, allows people to express themselves, appreciates their point of view, feels comfortable giving rather than receiving Durga, he will have grown. He will be more Vishnu, fountainhead of security, and more people will be attracted to him.

Growth happens when more people can depend on us

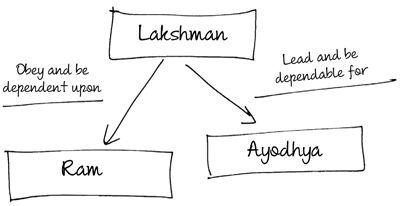

In the Ramayan, Lakshman is the obedient and loyal younger brother of Ram, following him wherever he goes, doing whatever he is told to do. One day, Ram tells Lakshman, "I want solitude so I am shutting the door of my chambers. Do not let anyone in. Kill anyone who tries to open it." Lakshman swears to do so.

No sooner is the door shut than Rishi Durvasa, renowned for his temper, demands a meeting with Ram. Lakshman tries to explain the situation. "I don't care," says an impatient and enraged Durvasa, "If I don't see the king of Ayodhya this very minute I shall curse his kingdom with drought and misfortune." At that moment Lakshmana wonders what matters more: his promise to his brother, or the safety of Ayodhya? What decision must he take? Must he be karya-karta or yajaman?

Lakshman concludes that Ayodhya is more important and so opens the door to announce Durvasa. But when he turns around there is no sign of Durvasa. And Ram says, "I am glad you finally disobeyed me and decided Ayodhya matters more than Ram."

The tryst with Durvasa makes Lakshman ask the fundamental question, "For whom are you doing what you are doing?" Lakshman realizes in his yagna, all his life, Ram was the only devata. But with this decision, he has made all of Ayodhya his devata. His gaze has expanded. Until then only Ram could depend on him. Now all of Ayodhya can depend on him.

Lakshman realizes that obedience is neither good nor bad. What matters is the reason behind the obedience, the belief behind behaviour. Is it rooted in fear or is it rooted in wisdom? Does he obey to ensure self-preservation, self-propagation and self-actualization or because he cares for the Other? A yagna is truly successful when the svaha helps both devata and the yajaman outgrow dependence.

When Shailesh moves, he takes his team with him. So everyone knows when Shailesh resigns from a company, six more people will go. Shailesh thinks of this as his great strength. He has a power team that can change the fortunes of a company. He does not realize this is also his weakness. He does not see new talent and new capabilities and capacities. His team is his comfort zone and he is assuming they will be strong and smart enough for any situation. Will they be as successful in a new situation, in a new market, when economic realities change, when resources are scarce, when clients demand different things? Shailesh will grow only when he is able to expand his team, include new people, allow people to move out, work on their own. He is growing too dependent on his team and they are too dependent on him. It is time for him to become more independent, to become dependable to others.

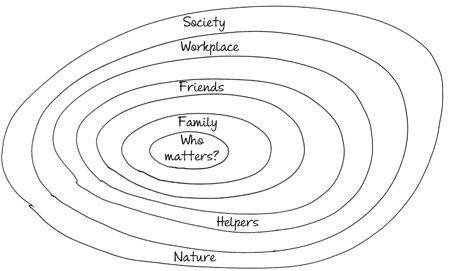

Growth happens when even the insignificant become significant

For eighteen days, the Kauravs and the Pandavs fight on the plains of Kurukshetra. Hundreds of soldiers are killed on either side. In the middle of the war, Krishna tells Arjun, "We have to stop. The horses are tired. They need to rest and be refreshed. Shoot your arrow into the ground and bring out some water so that I can bathe and water the horses. Keep the enemy at bay with a volley of arrows while I do so." Arjun does as instructed. Refreshed, the horses pull the chariot with renewed vigour.

The horses pulling Arjun's chariot did not ask to be refreshed. Krishna sensed their exhaustion and made resources available so that they could be comforted. Often, we forget the 'horses' that help us navigate through our daily lives. Horses are a crude metaphor for those who make our lives comfortable but who do not have much of a voice when it comes to their own comfort. In every office, especially in India, there are a host of people who keep the office running—the office boy, canteen boy, security guard, drivers, peons, and so on. This is the silent support staff. They take care of the 'little things' that enable us to achieve the 'big things'. A simple study of how organizations treat this silent support staff is an indicator of leadership empathy.

Randhir drives his boss to work every day negotiating heavy highway traffic for over two hours to and fro. His boss, Mr. Chaudhary, is a partner in a large consulting firm that is responsible for over fifty high net-worth clients. This means a lot of travel both in the city and outside, which means many trips to the airport early in the morning and late at night. This also means travelling from meetings from one end of the city to another and short trips to satellite cities. Randhir is frustrated. His boss does not know that he lives in a shantytown an hour away from Mr. Chaudhary's swanky apartment block. To travel to his place of work, he needs to take a bus or an auto. These are not easily available early in the morning or late at night. His travel allowance is insufficient to take care of this. When he raised this issue with Mr. Chaudhary, he was told, "This is what the company policy says you should be paid." Randhir does not understand policy. He serves Mr. Chaudhary, not the company. But Mr. Chaudhary does not see it that way. And then there are Sundays when Mr. Chaudhary visits his farmhouse with his wife and children. No holidays for Randhir. "His family is in the village so why does he need a holiday?" Often there is no parking space at places where Mr. Chaudhary has meetings. At times, there are parking spaces but no amenities for drivers—no place to rest and no bathrooms. "You cannot eat in the car; I do not like the smell," says Mr. Chaudhary, who also disables the music system when he leaves the car "so that he does not waste the battery." And when Mr. Chaudhary got a huge 40 per cent bonus over and above his two crore rupee CTC, he very generously gave Randhir a 500 rupee hike. "I am being fair. That's more than the drivers of others got. I don't want to disrupt the driver market."

Growth happens when we include those whom we once excluded

In the Mahabharat, during the game of dice, Yudhishtir gambles away his kingdom and then starts wagering his brothers. He begins with the twins, Nakul and Sahadev, and then gambles away Bhim and Arjun, then himself and finally, their common wife, Draupadi.

Later, during his forest exile, his brothers drink water from a forbidden pond and all die. The guardian of the pond, a stork, offers to resurrect to life one of the four brothers. Yudhishtir asks for Nakul to be resurrected. "Why not mighty Bhim or the archer Arjun?" asks the stork. To this Yudhishtir replies, "Because Nakul is the son of Madri, my father's second wife. If I, son of Kunti, first wife of my father, Pandu, am alive, surely a son of Madri needs to survive too. When Madri died, Kunti promised to take care of her children. I have to uphold my mother's promise."

Thus, we see a transformation in Yudhishtir. The stepbrother who is the first to be gambled away is also the first to be resurrected. He, who was excluded before, and hence dispensable, has been included. The king who sacrificed the least fit person now helps the most helpless. Yudhishtir's gaze has thus expanded from taking care of himself to taking care of others. His mind has expanded and he has risen in varna. He has become more dependable. He has grown.

At a party, Karan met Mansoor, who had unceremoniously fired him years ago. He found himself caught up in a dilemma. Should he speak to Mansoor, relive those ugly memories? Should he discreetly avoid eye-contact? Suddenly, Mansoor waved to him with a smile and asked him to join the group he was with. "This is Karan," he said, "We worked together a long time ago." He did not mentioning the firing or the unpleasantness of the past. He had moved on in his mind, and made no attempt to justify his action or apologize. Karan, who was once excluded, suddenly felt included. It felt good.

Growth happens when we stop seeing people as villains

In the final chapter of the Mahabharat, Yudhishtir renounces his kingdom and passes on his crown to his grandson Parikshit and sets out for the forest. His wife and brothers follow him. As they are climbing the mountains, they start falling into the deep ravine below, one by one. Yudhishtir does not turn around to help them, "Because," he says, "I have renounced everything."

When he is alone, with no one but a dog for company, Indra opens the gates of Amravati and lets him in. "Dogs are inauspicious," says Indra, "This dog cannot come in." Yudhishtir refuses to enter Amravati without the dog because the dog has been his one true companion. Indra relents.

Inside Amravati, Yudhishtir finds the Kauravs enjoying the joys of paradise. "How can that be?" asks Yudhishtir angrily, "If these warmongering villains can be allowed here, surely my brothers should be allowed here too. Where are they?"

At this point Indra says, "You demand that your unconditional follower enter paradise with you, but you are unwilling to share paradise unconditionally with those who have already been punished for their crimes. When will you forgive them, Yudhishtir? How long will you hold on to your anger? Can Swarga be yours unless you lead unconditionally?"

Inclusion means not just allowing those who follow you into paradise, but also making room for those who reject and oppose you. This is brahmanavarna.

Vimla is happy with herself. There was a time she would find disorganized people very irritating. She would try to correct them. And punish them if they resisted. Over the years, as she rose to head the audit department, she realized that different people function differently. That it was perfectly fine to not be as organized as she herself was, or be differently organized. She no longer mocks those who are different. She includes them. She has grown.