Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (52 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

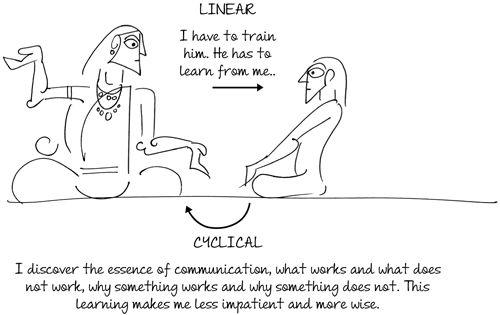

In business, it is easy to get cynical about people's ability to learn and think that the only way to get work done is by dominating or domesticating others with rules and systems, by using reward and punishment to coerce them into being ethical and efficient. This approach only reveals impatience and a closed mind.

If we are convinced we know everything there is to know about the world, we create a world with little understanding of humanity, where humans are just animals to be controlled and directed. A society thus created, one without faith, is no society at all. It is a warzone waiting to explode.

To understand why people refuse to do as they are told, why they defy and subvert the system, we need Sharda. To get Sharda, the yajaman has to give Vidyalakshmi freely and introspect why the devata resists receiving it, why he would rather obtain fish than learn to fish, why he would rather be dependent and complain about others instead of taking responsibility and becoming dependable.

Ravi compares his mining business to collecting water from a well. When there is a high demand in the market, he widens the bucket and when the demand is low, he narrows it. With this approach of his, he is revealing that he looks at his organization as a mere bucket, a thing. People are just tools to be used as long as they are useful. And then he wonders why, despite being hugely successful, no one is his family looks up to him or cares for him. They fear him, and obey him, but do not appreciate him. He is not in a happy place and will continue to be unhappy if he doesn't widen his gaze to learn and grow.

Growth in thought brings about growth in action

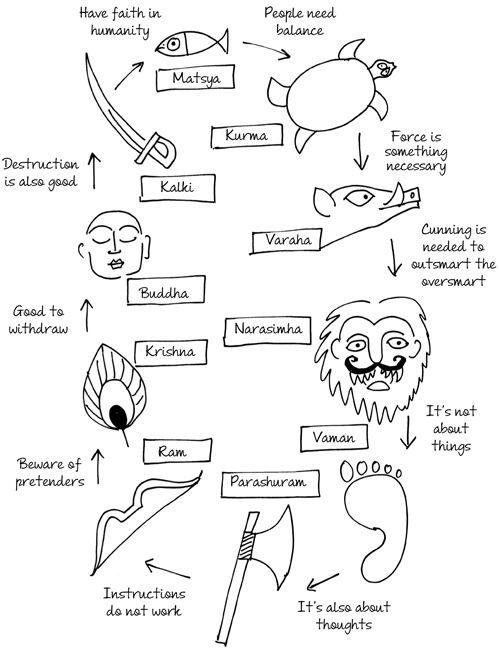

As Vishnu goes about preserving the world, provoking everyone to expand their gaze, we discover how each of his avatars is based on the learning from previous avatars:

- As Matsya, the small fish, who is saved from the big fish by Manu and who saves Manu from pralay, he learns that humanity needs to learn moderation and balance. The helpless cannot be helped at the cost of the environment; the act of feeding must be accompanied by the encouragement to outgrow hunger.

- This leads him to become Kurma or the turtle who upholds the churn that functions only when force is balanced by counter-force, when both parties know when to pull and when to let go. Then he observes the animal nature of man that makes him aggressive, territorial and disrespectful of the boundaries of others.

- In the next avatars of Varaha, the boar, and Narasimha, the man-lion, he uses force to overpower and cunning to control the animal instinct. This does not stop the rise of Bali, who believes that all of life's problems will be solved by distributing wealth. Vishnu learns that humanity needs to expand its gaze from things to thoughts, from Narayani to Narayan.

- So Vaman, the priest, becomes Parashuram, the warrior-priest, who tries to instruct humanity on the value of thoughts over things. When instruction does not work, he becomes Ram, leading by example. But then that leads to pretenders who value rules in letter, not spirit. This leads to the birth of Krishna.

- In the final two avatars, Vishnu breaks the system, almost acting like Shiva, the destroyer, passively withdrawing as a hermit (Shramana, sometimes identified with the Buddha), or actively destroying it like a warlord as Kalki. The point of the destruction is to provoke wisdom.

- With culture gone, nature establishes itself in all its fury. The law of the jungle takes over. The big fish eat the small fish until Manu saves the small fish and reveals that there is still hope for humanity. In this act of saving the fish, humanity displays the first stirrings of dharma, the human potential, motivating Vishnu to renew his cycle once more.

Vyas who put together the Mahabharat and the Purans is described as throwing up his hands in anguish over why people do not follow the dharma that benefits all. Vishnu, on the other hand, is never shown displaying such anguish. The transformation of Brahma is not his key performance indicator. Following dharma is not necessary. It is desirable. If not followed, the organization will collapse, but nature will survive and life will go on. So Vishnu smiles even though Brahma stays petulant.

Birendra believes his father Raghavendra is a successful man because he has made a lot of money. However, for Raghavendra money is not the objective but the outcome of intellectual and emotional growth. He began as a clerk in a small chemical company. He learned new skills and understood how the world worked, gradually becoming more and more successful in every task he undertook. He became an executive, a manager, even a director of his firm before he decided to break free and become an entrepreneur. His learning continued as he decided to mentor more companies as an investor. Before long he became the owner of many industries, but never ceased to learn, observing what made people give their best and what made them insecure. This knowledge made him a better negotiator and deal-maker. He shares his ideas freely and creates opportunities for people to grow, but very few see Saraswati the way he does. Naturally, they are neither as successful nor as content as he is.

To provoke thought, we have to learn patience

The way Shiva provokes thought is very different from the way Vishnu does. Brahma chases his daughter Shatarupa, which is a metaphor for human attachment to belief. In fear, we cling to the way we imagine the world and ourselves. Shiva beheads Brahma for this. Shiva also beheads Daksha for valuing the yagna over people. Beheading is a metaphor for forcing the mind to expand.

Shiva wants Brahma and Daksha to shift their focus from Narayani to Narayan. But both stubbornly refuse to grow. Shiva's insistence only frightens them further. In exasperation, Shiva shuts his eyes to Brahma and his sons, allowing them to stay isolated like ghosts trapped by Vaitarni, unable to find tirtha. Frightened deer and dogs bark in insecurity and seek shelter from the rather indifferent Shiva.

Shiva is called the destroyer because he rejects Brahma's beliefs, beheads him and holds his skull in his hand in the form of Kapalika. In contrast, Vishnu is called the preserver as he allows Brahma his beliefs, gives him shelter on the lotus that rises from his navel and waits for Brahma to expand his gaze at his own pace and on his own terms.

Vishnu keeps giving the devata the option to change, changing his strategies with each yagna, different avatars for different yugas, sometimes upholding rules, sometimes breaking them, hoping to provoke thought in the devata, to make him do tapasya until shruti is heard.

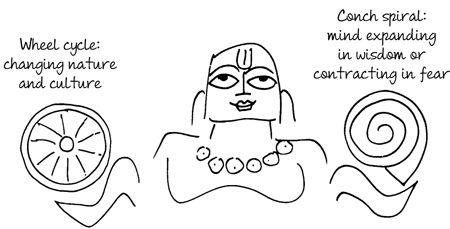

Like a mother gently persuading her child, Vishnu shows him two things: a wheel (chakra) and a conch-shell (shankha). The wheel represents the repetitive nature of prakriti and sanskriti: the changing seasons and the cycle of booms and busts that haunt the marketplace. The conch-shell represents the imagination that can spiral outwards in wisdom or inwards in fear.

If the devata expands his gaze, the yajaman grows in faith. If the devata does not expand his gaze, the yajaman grows in patience. Either way, the yajaman grows. He sees more, he becomes more inclusive. He does not frighten away investors, talent, or customers who naturally gather around this patient, accommodating being. Thus Lakshmi walks his way.

All her working life, Maria has heard Kamlesh scream, "You will not understand. Just do what I tell you." She has been his secretary for twenty years and she knows that Kamlesh is a brilliant man who wants to share his knowledge with the world, but he has very little patience. As chief designer, he tries hard to explain his designs to his team but they just do not get it. He wins numerous awards and so many designers want to work with him, but while they work with him, few really try and appreciate what makes Kamlesh so brilliant. Kamlesh's thoughts are spatial, not linear. He sees patterns and thinks on his feet, changing ideas constantly, relying very much on instinct. He tries to explain this 'process' but it is very difficult to articulate. When those around him are not able to catch up with him, he loses his temper, shouts at them, calls them names and throws them out. Maria has been able to figure him out enough to know how to work with him. While she does not understand his design work, she knows how to get his administrative work done. She knows he is not as nasty as people think he is. He is like Shiva, quick to temper, easy to please, demanding too much of his students, unable to see that the world does not have the same line of sight as he does. The only other person who understands Kamlesh is Hamir, the head of the art department at the university. "Kamlesh," he says, "Why do you get angry? They will learn when they are supposed to. You just have to provide the input. Do not expect any output. I know it is frustrating but after teaching for thirty years I realize students will follow their own path. They will indulge you by obeying you. The point is not to get them to obey; the point is to inspire them to expand their own mind for their own good. If they don't, who loses?" So saying Hamir smiles.