Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (54 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

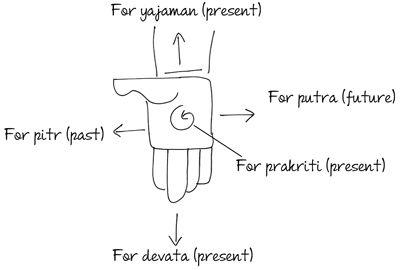

An enterprise does not exist in isolation. It depends on the past and exists for the future. It depends on the environment and exists for society. Everyone matters and everyone needs to be balanced.

If too much is given to the devata, too little remains for the yajaman and vice versa. If too much value is placed on the past, there will be no innovation. If too much value is paid to the future, mistakes of the past will come back to haunt us. If culture matters more than nature, then one day nature will be destroyed, and with it culture. If nature begins to matters more than culture, then the point of being human is lost. He who preserves all five is Vishnu, the preserver. He creates an ecosystem where there is enough affluence and abundance to satisfy all.

When Ramson started his retail company he told everyone that the customer is god and everything must be done to give the lowest price to the customer. In the past five decades, the company has grown in size making it the darling of the stock exchange. But few notice that this has been done at a terrible cost. The low prices of goods has led to ridiculous consumption patterns in consumers, low wages and poor benefits to employees. Moreover, overproduction to ensure large scale demand and low prices has damaged the environment, and led to the outsourcing of vendors and related business to other countries resulting in unemployment. The only one to be fed by this yagna is Ramson. By focusing on one devata, he has denied food to everyone else.

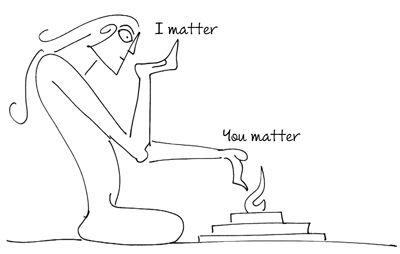

How the devata sees the yajaman reveals the gap in meaning

Does business create the businessman, or is it the other way around?

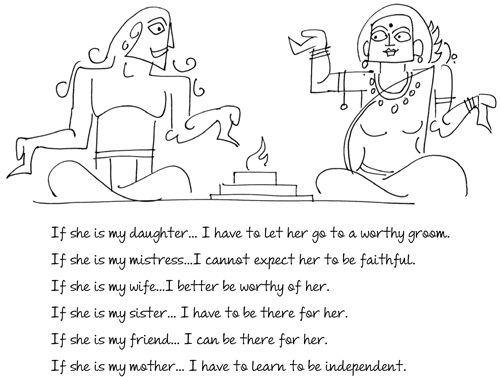

Every yajaman is convinced he is either father of the yagna, or the entitled benefactor of the tathastu, but it is the devata who decides if the yajaman is an incestuous, abusive father, an unworthy groom, or a beloved worthy of courting and following. The devata is the darpan or mirror that reveals the gap between how we imagine ourselves and how the world imagines us.

- If the devata feels controlled and judged, the yajaman is like Daksha, who does not let his daughter, Sati, choose her own groom. Sooner or later, Sati's chosen groom, Shiva, will behead him.

- If the devata feels ignored, it means the yajaman is being seen as Indra, who treats his queen like a mistress with a sense of entitlement rather than responsibility. He will find Sachi going to another groom, the asura.

- If the devata fearlessly provokes the yajaman to be more understanding, the yajaman is being seen as the wise Shiva lost in his own world, who needs to be coaxed by Gauri to open his eyes and indulge other people's gaze: help those in the crowded bazaar of Kashi see what he can see from the lofty peaks of Kailas. The devas and asuras may fight over amrit; but only Shiva has the maturity to drink the poison, without demanding compensation or seeking motivation.

- If the devata feels no resentment despite being treated as Renuka, beheaded for having just one adulterous thought; or as Sita, exiled because of street gossip; or as Radha, abandoned when duty calls; or as Draupadi, helped without obligation or expectation, the yajaman is being seen as trustworthy Vishnu whose acts are driven by wisdom and not fear, who does not seek to dominate or domesticate the world around him, but rather finds validation in helping every devata grow at his own pace. If talent, investors and customers chase the yajaman, he is Vishnu for sure.

Ratnakar is rather curt and tends to be impolite, yet the people who work for him love him. They know that in his heart he wants everyone to grow. He is constantly checking if people have learned more, earned more, done more. To the new worker he asks, "Have you gained more skills?" To the old worker he asks, "Have you taught your skills to another? Why not? Don't you want a promotion or do you want to be a labourer all your life?" To the supervisor he asks, "Do you know how to read account books and balance sheets? Why not? Do you want this department to make losses? Do you want it to be shut down?" To the person who leaves his company, "I hope you are leaving for a better place and not because you are unhappy here." Ratnakar's sharp words seek to stir the Narayan potential in everyone. For people around him, he is Vishnu and they trust him.

The tathastu we give reveals the meaning we seek

Tathastu or what we give in exchange for what we have received can be of three types:

- Dakshina, which is a fee for goods and services received.

- Bhiksha, which is conditional charity that makes the yajaman feel superior.

- Daan, which is unconditional charity that makes the yajaman wise.

Dakshina is exchanged for Lakshmi, bhiksha for Durga and daan for Saraswati. Only daan creates ranga-bhoomi, not the other forms of tathastu.

On the day they had to go their separate ways, two childhood friends took an oath that they would always share their possessions with each other. In time, one rose to wealth while the other was reduced to abject poverty. The poor friend, driven to desperation, decided to seek the help of his rich friend, reminding him of their oath. The story takes different turns in the Mahabharat and the Bhagavat Puran.

In the Mahabharat, the rich friend is Drupad, king of Panchal, and the poor friend is Drona, a priest. On his arrival, Drona acts familiar with the king, reminding him of his childhood promise and expects at least a cow from Drupad, almost as if it were his right. Drupad does not take to this kindly and tells Drona, "Childhood promises cannot be taken so seriously: we were equals then, but now we are not. As king, it is my duty to help the needy. Ask for alms and you shall get them." Drona is so humiliated that he leaves Drupad's court, learns the art of warfare, teaches it to the princes of the Kuru clan, and as tuition fee demands that they procure for him one half of Panchal so that he can be Drupad's equal. When this is achieved, an angry Drupad seeks from the gods two children: a boy who will kill Drona and a girl who will divide and destroy the Kuru clan that helped Drona.

In the Bhagavat Puran, the rich friend is Krishna, who lives in Dwaraka, and the poor friend is Sudama, a priest. Not wanting to go empty handed, Sudama forsakes a meal so that he can offer a fistful of puffed rice to his friend whom he is meeting after several years. Krishna welcomes Sudama with much affection and orders his queens to bathe and feed him. Sudama feels awkward asking his friend for a favour, especially during their first meeting in years. He keeps quiet. When he returns home, he finds, to his surprise, gifts of cows and grain and gold waiting at his doorstep.

The mood in the Mahabharat story is full of rage. Drupad can give daan but offers bhiksha instead. Finally Drona takes dakshina from his students to satisfy his hunger. What is simply about hunger initially becomes an issue of status, for Drupad not only denies Lakshmi but also strips Drona of Durga by insulting him. Both sides speak of rights and duties, blaming and begrudging each other. All this culminates in a war where both Drupad and Drona die, none the wiser.

The mood in the Bhagavat Puran story is full of affection. Krishna gives daan. He gives Lakshmi and Durga and in exchange he receives Saraswati. He observes Sudama's wisdom: how by starving himself he creates a svaha of puffed rice, transforming his meeting into a yagna with Krishna as the devata; how he does not make the receipt of tathastu an obligation for he is sensitive to the context that the current situation is very different from the childhood one. Krishna observes that Sudama knows he can claim no rights over Krishna nor impose any obligations on him. Sudama reveals to Krishna that it is possible for people to be generous and kind, even in abject poverty.

Sudama presents himself, without realizing it, as an opportunity for Krishna to give away his wealth voluntarily and unconditionally. Krishna does so without being asked because he is sensitive enough to realize how poor and helpless his friend is. That he expects nothing from Sudama indicates Krishna's economic and emotional self-sufficiency. Thus, he becomes a mirror to human potential.

In the Mahabharat story, Drona and Drupad end up in the rana-bhoomi because each is convinced the other is wrong. In the Bhagavat Puran story, Sudama and Krishna are in the ranga-bhoomi where each respects the mask imposed by society but is still able to do darshan of the human being beyond this mask—the human being who can seek help and offer help.

Mani has two sugar factories. As far as he is concerned, he is doing his workers a great favour by giving them jobs. Without him, they would be jobless. He wants them to be eternally grateful to him. He even wants his son to be grateful as he is getting a huge inheritance on a platter. Mani is giving bhiksha to all and by doing so strips them of power. Naturally everyone resents Mani. The workers would rather have their dues fairly paid as dakshina, for they help Mani generate Lakshmi. Nobody is learning anything from the exchange; there is no daan to be seen anywhere.

We alone decide if we need more meaning, another yagna

Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs believe in rebirth. Rebirth is what distinguishes the mythologies of India from the rest of the world. When the word 'rebirth' is used even the most learned people immediately think of physical rebirth. However, for the great sages of India, rebirth referred to physical, social and mental rebirth owing to the three bodies of every human: sthula-sharira, karana-sharira and sukshma-sharira, nourished by Lakshmi, Durga and Saraswati.

- The rebirth of the physical body is a matter of faith, not logic. It can neither be proved nor disproved.

- The rebirth of the social body is not under our control, as it is impacted by social vagaries: the rise and fall of individual and market fortunes. With this comes a change in personality, which is temporary.

- The rebirth of the mental body is a matter of choice. We can spend our entire lives imagining ourselves as heroes or martyrs. Or we can seek liberation from these finite imaginations by realizing that these are stories we use to comfort ourselves. No one knows what the truth really is. All we can do is let our mental body die at the end of the previous yagna and allow it to be reborn at the start of the next yagna, with a little more sensitivity, recognizing that every devata imagines himself as hero or martyr, not villain.