Candyfloss (9 page)

Authors: Nick Sharratt

I sat there and sat there and sat there, and when Dad came back eventually clutching his Polaroid I had a short burst of swinging and smiled at the camera.

‘It’s a great swing, isn’t it!’ said Dad proudly, as if he had made it all himself. ‘Hey, why don’t you phone Rhiannon and see if she wants to come round and play on it too?’

I hesitated. I’d asked Rhiannon round to play heaps of times, but always at Mum’s. I’d wanted

to

keep my time at the weekend specially for Dad. But now

all

my time was with Dad.

‘Go on, phone her,’ said Dad. ‘Ask her round to tea. Does she like chip butties?’

I wasn’t sure. We always ate salads and chicken and fruit at Rhiannon’s. Her school packed lunches were also ultra-healthy options: wholemeal rolls and carrot sticks and apples and weeny boxes of raisins. But maybe chip butties would be a wonderful wicked treat?

I knew I was kidding myself. I suspected it would be a big big big mistake to invite her round. But I felt so weird and lonely stuck here with Dad with nothing to do. If Rhiannon was here we could muck about and do silly stuff and maybe I’d start to feel normal again.

I phoned her up. I got her mum first.

‘Oh Flora, I’m so glad you called! How

are

you?’ she asked in hushed tones. ‘I was so shocked when Rhiannon told me about your mother.’

She was acting as if Mum had

died

.

‘I’m fine,’ I lied. ‘Please can Rhiannon come round to tea?’

‘What, today? Well, her grandma and grandpa are here. Tell me, Flora, do you see your grandma a lot?’

‘My grandma?’ I said, surprised. ‘Well, she sends me birthday presents, but she doesn’t always

remember

how old I am. Dad says she gets muddled.’

‘What about your mum’s mum?’

‘She died when I was a baby. There’s Steve’s mum, but I don’t think she likes me much.’

‘You poor little mite. Well, listen to me, sweetheart. Any time you need to discuss anything girly, you come and have a word with me, all right? I know your dad will do his best, but it’s not the same, not the same at all. A growing girl needs her mother. I just can’t understand how

your

mother . . .’ She let her voice tail away.

I clutched the phone so tightly it was a wonder the plastic didn’t buckle. I couldn’t stand her going on like that, as if Mum had deliberately abandoned me. I decided I didn’t want Rhiannon to come round after all, but her mum was busy calling to her and asking for details of the address.

I heard Rhiannon saying stuff in the background. It didn’t sound as if she wanted to come round.

‘You’ve got to go! It’s the least you can do. Poor little Flora will be feeling so lonely,’ Rhiannon’s mother hissed.

‘I’m fine, really,’ I said.

‘Yes dear, I’m sure you are,’ she said, in a

don’t-think-you-can-fool-me

tone of voice.

I couldn’t fool Rhiannon either when she came

round

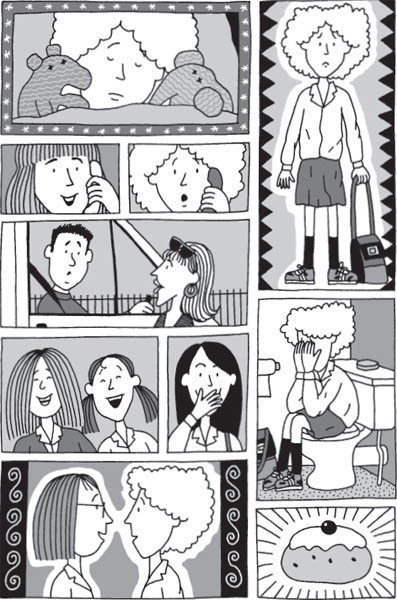

. She was wearing a lacy blue top and white jeans. She had one little plait tied with blue and white thread in her long glossy black hair. She looked beautiful. She seemed so out of place in our café.

‘Oh Floss, you poor thing, your eyes look so sore, all red and puffy,’ she said.

‘It’s an allergy,’ I said quickly.

Rhiannon sighed at me. She turned to Dad. ‘My mum says you must phone her if you’ve got any problems.’

Dad blinked. ‘Problems?’

‘You know. Over Flossie,’ said Rhiannon. She was acting like she was my social worker or something. Even Dad looked a bit irritated.

‘We haven’t got any problems, Floss and me, have we, doll-baby? But it’s very kind of your mum to offer all the same, so thank her very much. Now, would you two girls like to go and play on Floss’s swing?’

He led the way through the café, out into the kitchen, and opened the door to the back yard dramatically, as if Disneyland beckoned.

Rhiannon stepped warily into the back yard, walking as if she was wading through mud. She peered at the wheelie bins, the tarpaulins, the bits of bike. It was definitely a mistake inviting her round. I suddenly saw Rhiannon telling her mother

all

about our dismal back yard. Worse, I saw her telling Margot and Judy and all the girls at school.

I looked at her anxiously.

‘Oh, there’s your swing. How . . . lovely,’ she said.

‘I know it’s not lovely,’ I whispered. ‘But Dad’s fixed it all up for me specially.’

‘Sure. OK. I understand,’ said Rhiannon. She raised her voice so that Dad could hear in the kitchen. ‘Oh Floss, your swing looks great hanging on the apple tree,’ she said, enunciating very clearly, as if Dad was deaf or daft.

She hopped on it, had one token swing, then hopped off again. ‘So, shall we go up to your bedroom and play?’ she said.

‘Maybe we should swing a bit more,’ I said.

‘But it’s, like, boring,’ said Rhiannon. ‘Come on, Floss, I’ve been nice to your dad. Now let’s go and do stuff.’

‘OK.’

We went back indoors. Dad had started peeling potatoes in the kitchen. He looked baffled to see us back so quickly.

‘What’s up, girls?’ he said.

‘Nothing’s up, Dad. I – I just want to show Rhiannon my bedroom,’ I said.

I didn’t didn’t didn’t want to show her my bedroom.

She looked round it, sucking in her breath. ‘Is

this

your bedroom?’ she said. She wrinkled her brow. ‘But I don’t get it. Your bedroom’s lovely, all red and white and clean and pretty.’

‘That’s my bedroom at my mum’s, you know it is,’ I said.

I sat on my old saggy bed and stroked the limp duvet, as if I was comforting it.

‘So OK, where’s all your stuff? The cherry curtains and the red velvet cushions and your special dressing table with the velvet stool?’

‘I’ve got all my clothes and books and art stuff here. The curtains are still at Mum’s and the other things have been put into storage. They wouldn’t fit in my bedroom here.’

I

scarcely fitted in my bedroom at Dad’s. It was not much bigger than a cupboard. There was just room for the bed and an old chest of drawers. Dad had started to paint it with some special silver paint, but it was a very small tin and it ran out before he could cover the last drawer. He’d propped a mirror on top of the chest and I’d laid out my brush-and-comb set and my china ballet dancer and my little cherry-red glass vase from my dressing table at home. They didn’t make the chest look much prettier.

‘Dad’s going to finish painting the chest when he can find some more silver paint,’ I said. ‘And

he

’s going to put up bookshelves and we’re going to get a new duvet – midnight-blue with silver stars – and I’m going to have those luminous stars stuck on the ceiling

and

one of those glitter balls like you get at dances – and fairy lights – and – and—’ I was running out of ideas.

Rhiannon looked at me pityingly. ‘What sort of house is your mum going to have in Australia?’ she asked.

‘They’re just renting. It’s just some little flat,’ I said.

I was lying. Mum had shown me a brochure showing beautiful modern flats with balconies and a sea view. They’d deliberately chosen a flat with three big bedrooms so that I could have the room of my dreams.

‘It couldn’t be littler than this flat,’ said Rhiannon. ‘You must be a bit nuts to want to stay here rather than go to Australia.’

‘I want to be with my

dad

,’ I said.

‘Do you love your dad much more than your mum then?’

‘No, I love them both the same. But Dad needs me more,’ I said.

‘Well, it still seems crazy, if you ask me,’ said Rhiannon, sitting down on the bed beside me. It creaked in protest. She peered down at it, shaking her head in disgust.

‘Well I’m

not

asking you,’ I said. ‘And anyway,

you

were the one who said I didn’t have to go. I thought you wanted me to stay so we could be best friends for ever. Don’t you want to be my best friend now, Rhiannon?’

‘Of course I do.’

‘We’re best friends for ever?’

‘Yes, like for ever and ever, dummy,’ said Rhiannon, sighing and shaking her long hair over her shoulders.

She was saying all the right words but she was saying them in this silly American accent

.

9

I HAD MORE

bad dreams that night. I wished I’d kept my great big Kanga to cuddle in bed. I couldn’t believe I’d actually thrown away all my old teddies. All I had was the limp lopsided elephant and dog that Grandma had knitted me. I reached out of bed and tucked one on either side of my head. They didn’t look very fetching but they

felt

warm and soft, like a special scarf.

I lay awake worrying that the bad dreams would come back the minute I closed my eyes. It helped that every time I wriggled round on my pillow a soft little knitted paw patted me.

I fell asleep just as it was starting to get light – and then woke with a start. Something was ringing and ringing and ringing. The telephone! I stumbled out of bed and ran to answer it. Dad lumbered behind me in his pyjamas, huffing and puffing.

‘Hello?’ I said into the phone.

‘Oh,

there

you are, Floss! I’ve been ringing for

ages

!’ said Mum. ‘I thought you and Dad must have left for school already. What are you doing, having breakfast?’

‘Um – yes,’ I said, not wanting to tell Mum we’d slept in. She sounded so

close

, as if she was back in our house across town. ‘Oh Mum, have you come back?’ I said breathlessly.

‘What? Don’t be silly, darling, we’ve only just got here. My Lord, what a journey! Do you know, Tiger didn’t sleep a wink the entire flight. Steve and I were just about going demented.’

‘I can imagine,’ I said.

‘But never mind, we’re here now, and you should just see the apartment, Floss. I feel like a film star! We’ve got a fantastic sea view and even though it’s winter here it’s so bright and sunny. I just can’t believe how beautiful it all is. It would all be so perfect if only you were here too. Oh Floss, I miss you so!’

‘I miss you too, Mum. So so much,’ I whispered. I didn’t want to be tactless to Dad, but he patted my shoulder reassuringly to show me he understood.

‘I just

know

you’d love it here. If you could just see for yourself how lovely everything is you’d jump on a plane tomorrow, I know you would. Oh darling, are you all right? Is Dad looking after you OK?’

‘Yes, Mum, I’m fine, really.’

‘He’s giving you proper food, not endless fry-ups and cakes and chip butties?’

‘Yes, Mum,’ I said.

I was still feeling queasy from last night’s chip butties. Rhiannon had been a little bit rude about them when Dad served them up for our tea.

Very

rude, actually. I’d felt so sorry for Dad I’d said quickly, ‘Well goody-goody, if you don’t like them that means there’s all the more for me.’ I’d ended up eating all my chip butties

and

Rhiannon’s.

Dad boiled eggs and ran down to the corner shop and bought tomatoes and cucumber and lettuce to make Rhiannon her own special salad, but she only ate two mouthfuls, and she didn’t appreciate him turning them into a funny face for her.

‘Does your dad think I’m, like, a baby?’ she said.

‘Dad’s bought special salad stuff,’ I told Mum truthfully. ‘And he’s fixed up a new swing in the garden and I’ve had Rhiannon round to play.’

‘That’s good,’ said Mum. ‘Well, I don’t want to make you late for school, sweetheart. You take care now. I’m going to send you lots of photos of our flat and the beaches and the parks and the opera house. Once you see them I just know you’ll be dying to come and join us.’

I swallowed. I didn’t know what to say. Most of me

ached

to be in Australia with Mum. But not without Dad.

‘Do you want to speak to Dad, Mum?’

‘Well, I’ll have a little word, yes please. Goodbye then, Floss. I love you so much.’

‘Goodbye, Mum. I love you too,’ I said.

I leaned against Dad while Mum questioned him. She sounded like a nurse taking a full medical history.

She asked:

- Is Floss looking mopey?

- Has she cried much?

- Is she sucking her thumb a lot?

- Is she as chatty as usual?

- Is she really eating properly?

- Is she having trouble getting to sleep?

- Did she wake up at all in the night?

- Is she having bad dreams?

I started to expect her to ask how many times I’d been to the toilet.

‘She’s

fine

,’ Dad kept saying. ‘For pity’s sake, you’ve only been gone five minutes. She’s not likely to have gone into a nervous decline already. Now, we’d better be leaving for school. What? Of course she’s had breakfast,’ said Dad, crossing his fingers in front of my face. He said goodbye and then put the phone down.

‘Phew!’ he said. ‘Oh dear, Floss, let’s shove some breakfast down you quick. I’m not sure there’s time for egg and bacon—’

‘I don’t want breakfast, Dad, there’s not

time

. I’m going to be late.’

‘No, no, you’ve got to have something inside you. Cornflakes? I’ll shove my jeans on and sort something out while you run and get washed and dressed.’